LJUBLJANA, Slovenia — In June 2024, Slovenia’s parliament voted to recognize a Palestinian state only one week after Spain, Ireland and Norway had taken that dramatic step.

Half a year later, Slovenian public broadcaster RTV — citing the ongoing war in Gaza—became the first in Europe to demand Israel’s exclusion from the 2025 Eurovision Song Contest. This past May, RTV warned it might boycott future editions of Eurovision if Israel isn’t expelled.

Over the summer, Slovenia banned imports from Jewish settlements in the West Bank, only a week after prohibiting all weapons trade with Israel — the first EU member to do so. That ruling followed on the heels of another one declaring two right-wing Israeli officials persona non grata. Last week, it became the first EU country to impose a travel ban on Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“People are dying in Gaza because they are systematically denied humanitarian aid,” the government said in announcing the arms embargo. “In such circumstances, it is the duty of every responsible country to act, even if that means taking a step before others do.”

Some analysts have pegged the aggressive anti-Israel stance as a gambit ahead of the country’s upcoming elections, when the country’s pro-Israel right will try to retake control after losing power in 2022.

But for Slovenia’s roughly 100 Jews, the campaign against Israel is part of a pattern of hostility that transcends the vagaries of politics. Barely five years ago under a right-wing government, a Slovene court voided the 1946 treason conviction of executed Nazi collaborator Leon Rupnik, who nearly liquidated the country’s Jewish population.

“Slovenes always want to be on the side of the underdog, and the media perception over the last 40 years is of poor Palestinians and big, imperialist Israel who took their land,” said Robert Waltl, president of the Liberal Jewish Community of Slovenia. “But now, because of the war, it’s worse here than any other former Yugoslav republic.”

Polona Vetrih, Robert Waltl and Sophia Huzbasic stand outside the Jewish Community Center in Ljubljana. (Larry Luxner)

Waltl spoke to JTA from his office at the Mini Theater, which since 2013 has also housed the Jewish Cultural Center and Slovenia’s only active synagogue. The 500-year-old building, which Waltl renovated with $1.6 million in donations, fronts Krizevniska Street in Ljubljana’s old city.

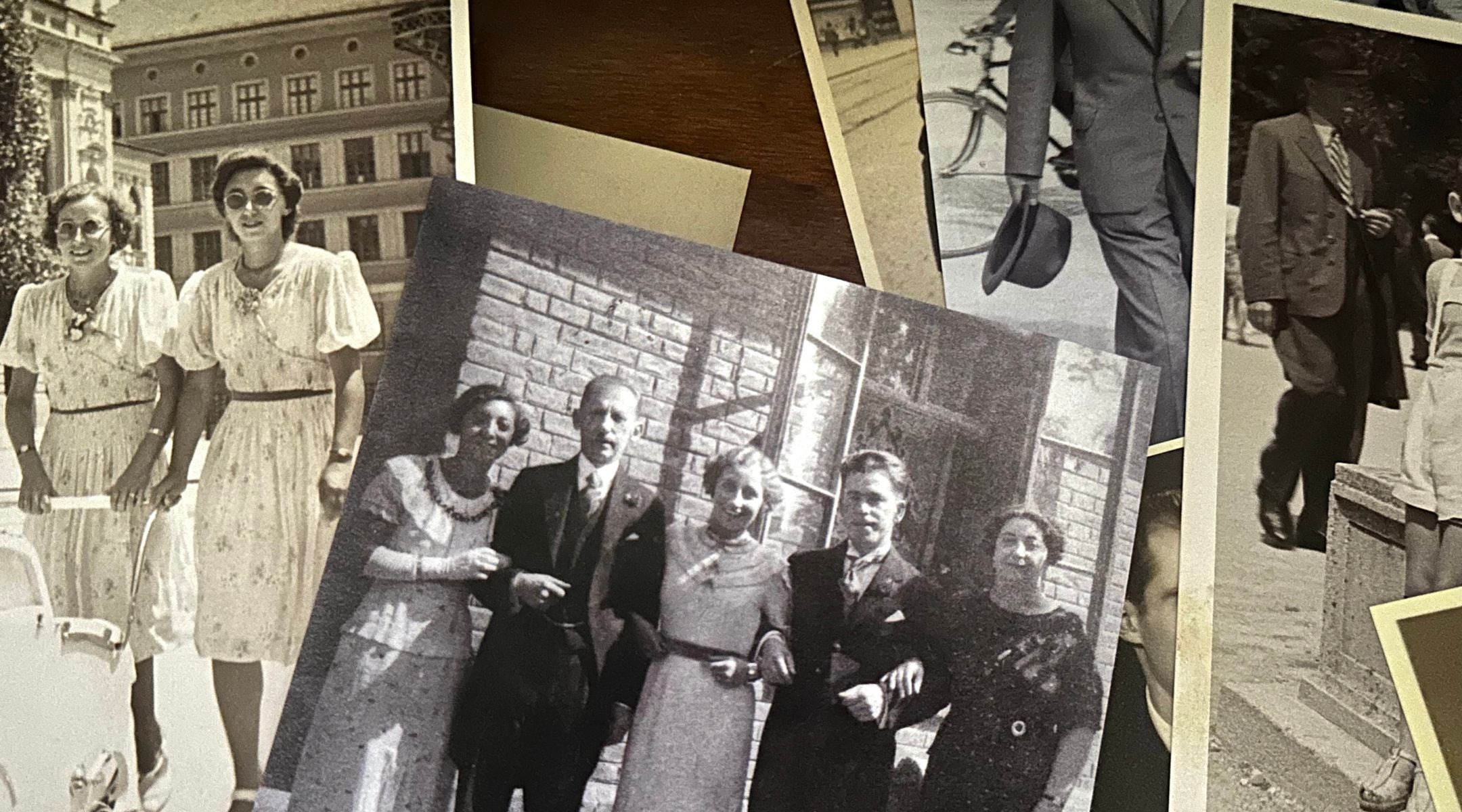

Its 6,500 square feet — crammed with prayer books, menorahs, historic photographs and an entire exhibit on the Holocaust — has become the focus of Jewish culture in Slovenia, with 2.1 million people the smallest and most prosperous of the six republics that once comprised Yugoslavia.

Unlike neighboring Croatia — whose center-right government has pursued a stridently pro-Israel policy despite a rising, homegrown fascist movement — Slovenia has veered sharply to the left in recent years.

“Christian antisemitism was very visible here before World War II,” Waltl, 60, explained as his dog, Umbra, repeatedly barked at passersby. “At the beginning of the 20th century, there was no university here, so people studied in Vienna — and the mayor of Vienna was very antisemitic. Students learned it there and brought it back home with them.”

The presence of Jews in Slovenia dates back to Roman times, with the first synagogue in Ljubljana built around 1213. During the Middle Ages, the most important community was in Maribor, though Jews were expelled from that town in 1496, and then from Ljubljana in 1515.

Historic photos of Slovene Jews murdered during the Holocaust are on display at the Jewish Community Center in Ljubljana. (Larry Luxner)

By the early 20th century, Slovenia’s Prekmurje region had become home to two-thirds of the country’s 1,400 Jews, mostly in the towns of Murska Sobota and Lendava. Yet antisemitism was pervasive; an outbreak of Jew-hatred during the 1929 economic crisis followed accusations that Jewish moneylenders were profiting from exorbitant interest rates. By the end of World War II, the Nazis and their collaborators had killed all but a handful of the country’s Jewish inhabitants.

During Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, Yugoslavia under Tito helped the fledgling Jewish state, but later, as head of the Non-Aligned Movement, he befriended Yasser Arafat and switched his allegiance. After Yugoslavia disintegrated in the early 1990s, the region was plunged into years of ethnic warfare that left an estimated 130,000 dead and millions homeless.

Only Slovenia escaped serious bloodshed, with only 62 deaths reported during its 10-day war of independence against the dominant republic, Serbia. Nevertheless, the Alpine republic — the same one that has just declared an arms embargo against Israel — became embroiled in a massive scandal involving weapons sales to Croatia and Bosnia & Herzegovina, both of which were fighting Serbia, despite a 1991 United Nations arms embargo.

Waltl said his country’s policy toward Israel, as well as domestic media, is riddled with hypocrisy and misinformation.

“In Croatia, the government strongly criticized what Hamas did on Oct. 7 and they stand with Israel. In Slovenia, it was the same for the first few days, but then all attention shifted to the plight of the Palestinians,” he said. “Today in Slovenia, 99% of the media isn’t just pro-Palestinian but anti-Israel. You will never hear that Israel was attacked by Hamas or Hezbollah, only that Israelis kill women and children.”

“Free Gaza” graffiti is scrawled on a metal barrier along a busy street in Ljubljana, Slovenia. (Larry Luxner)

He added: “It’s also true, however, that the right-wing government in Israel has crossed all acceptable lines and limits of humanity, triggering a wave of hatred towards Jews worldwide.”

It doesn’t help that Israel has never established an embassy in Ljubljana — even though Slovenia has maintained one in Tel Aviv for the past 30 years.

Polona Vetrih, a prominent stage actress whose father survived World War II as a partisan, said she’s had several unpleasant encounters with local antisemites. Recently, she sang at a peace concert where she performed the Ladino song “Adios Querida.”

“One girl from Palestine was very loud. She was screaming, and they threatened me. I was scared to death,” she said. “I went to the police afterwards.”

Frequently, she hears Slovenes complain that Jews are mean and think only of themselves.

“They don’t have a clue. Even during the Middle Ages, they blamed Jews for the plague,” she said. “I think it’s up to us to show them it’s not true.”

During communism, Slovenia had virtually no organized Jewish life. In 1991, the Liberal Jewish Community was established, and in 2002, local Jews contracted with a Chabad rabbi from Trieste, Italy, to conduct High Holiday services. The following year, said Waltl, the community received a Torah scroll from a British donor, and turned a nearby cigarette factory into a small synagogue with the help of the American Joint Jewish Distribution Committee.

Ten years ago, with the help of Lustig Branko — producer of the film “Schindler’s List” — the museum established a Festival of Tolerance. Last year, some 6,000 elementary school students came to see performances of “The Diary of Anne Frank.” Currently, liberal rabbis Alexander Grodensky of Luxembourg and Tobias Moss of Vienna visit Slovenia for special occasions.

In April 2024, a 10-member delegation from the World Jewish Congress traveled to Slovenia to meet with government officials, but they were ignored, Waltl said. And when swastikas were discovered scrawled on the walls of the Jewish Cultural Center one night, he said, “no one from the government came, and no one called me — not even the mayor of the city.”

Maya Samakovlija, the organization’s executive director of community relations, went even further.

Brass “stumbling stones” honoring Slovene Jewish victims of the Holocaust are displayed at the

Jewish Community Center in Ljubljana. (Larry Luxner)

“We were not merely ignored. What happened to us is something no other government in the world has done ever in the long history of the WJC,” said Samakovlija, who is based in Zagreb, Croatia. “Neither the prime minister, the president, the speaker of parliament, nor the minister of foreign affairs made any effort to meet with us. Instead, they sent only deputies and lower-ranking officials.”

At that meeting, Blanka Jamnišek, deputy head of Slovenia’s delegation to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, asked the visitors what they were doing “to promote a ceasefire and stop the killing of children, and the famine in Gaza,” according to Samakovlija and a statement that the AJC released at the time. The IHRA definition of antisemitism cites holding Jews collectively responsible for Israel’s actions as an example of antisemitism.

“Her colleagues were visibly shocked,” the WJC official said. “Once she had finished, I made the decision that we’d leave as a delegation. We stood up, ended the meeting and walked out.”

Ernest Herzog, the WJC’s executive director of operations, was also part of that delegation. He said Slovenia’s Jews “face an alarming rise in antisemitism, evident in acts of vandalism, threats and hostile rhetoric.”

“It is deeply troubling that certain officials have sought to justify this climate of intolerance through a distorted interpretation of the Middle East conflict — an excuse that is wholly unacceptable,” he added.

Politicians on the right more often support Israel. This past April, the Slovenia-Israel Allies Caucus was established by lawmaker Žan Mahnič of the Slovenian Democratic Party. Former Slovene Prime Minister Janez Janša, who supports the caucus, has said that if he returns to power, he will relocate his country’s embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and rescind Ljubljana’s recognition of Palestine.

Steve Oberman, an attorney in Knoxville, Tennessee, and past president of that city’s Arnstein Jewish Community Center, visited Slovenia in 2024 to teach a law class at the University of Ljubljana. He has since become a passionate defender of Waltl’s efforts.

“I’m disappointed that the Slovenian government isn’t doing a better job of supporting the Jewish community of Slovenia, given the country’s history,” Oberman told JTA in a phone interview. “Poor Robert has carried this task, almost singlehandedly, to revive Jewish life there and create a synagogue. I’m trying to work through our local Jewish community here in Knoxville to raise awareness, and hopefully some money.”

Meanwhile, the situation for the few Jews remaining in Slovenia isn’t getting easier.

Sophia Huzbasic, a native of Kyrgyzstan who lived for a time in Israel but settled in Slovenia nine years ago, said she was born with Soviet citizenship but chose to retain her Israeli passport.

A graphic designer, she lives in Ljubljana with her husband Igor, who’s from Sarajevo, Bosnia.

“For local Jews, I truly believe the antisemitism is really terrible,” she said. “I was raised in Moscow in the 1990s, so for me this is nothing. I’m not scared but I’m angry.”

Huzbasic, 43, said her bank refused to approve a car lease when officials learned she was an Israeli citizen — just one example, she said, of the insidious antisemitism that seems to be prevalent.

“We feel very angry because of the official position of the Slovenian government. What they’re doing is propaganda from a very poorly educated point of view, and they don’t want to widen their knowledge about the conflict,” Huzbasic said. “I totally disagree with the Israeli political situation, and I chose to keep my Israeli citizenship and live here. But now I’m very close to changing my mind. I cannot stop being a Jew.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.