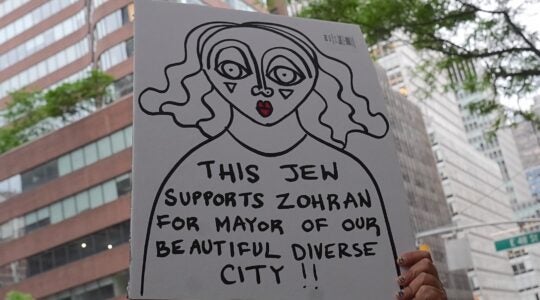

In recent days, nearly 1,000 rabbis have signed “A Rabbinic Call to Action: Defending the Jewish Future.” The letter, written in response to rising anti-Zionism and the rhetoric of political figures like New York City mayoral frontrunner Zohran Mamdani, affirms Israel’s right to exist and warns against the normalization of anti-Zionist language in public life.

It’s a passionate, well-intentioned statement — and it has ignited a painful public reckoning. Jewish communities are circulating spreadsheets of who signed and who didn’t. Some rabbis are being lauded for courage; others are being shamed or questioned for their silence. Congregants are searching the list to find their rabbi’s name, drawing conclusions about loyalty and belonging.

The very leaders tasked with holding the Jewish people together are, yet again, being torn apart.

Being a rabbi or cantor right now feels nearly impossible. We are expected to comfort the grieving, officiate under the chuppah, teach Torah, write and deliver sermons, model moral clarity, serve simultaneously as chief executives and moral guides, and hold divided communities together.

I have come to understand the challenges rabbis face as executive director of Atra, the national center I lead for rabbinic innovation and professional learning. Our forthcoming comprehensive study on the American rabbinate and rabbinic pipeline will show that while 97% of rabbis find their work deeply meaningful, many — especially those leading congregations — face unsustainable expectations.

And so, when a letter like this appears, rabbis can face a no-win choice: risk alienating some of the people they serve, or risk being seen as abandoning our people altogether.

There are many reasons a rabbi might choose not to sign a public political statement. Some lead communities that are split down the middle and fragile. Some worry about the erosion of trust that comes when clergy are seen as partisan. Some are thinking carefully about the changing enforcement of the Johnson Amendment and what “political activity” means for faith leaders and institutions today.

And yes, some rabbis may disagree with the letter’s framing or focus — but remain fully devoted to the safety and flourishing of the Jewish people.

Absence of a signature does not mean absence of love for Israel or for the Jewish people. It may reflect a different kind of leadership, one that prioritizes the relationships within a community over public declaration.

At Atra, we see this complexity every day — and we’re trying to help rabbis work through it. Together with Cara Raich, an expert facilitator and partner in this work, we’ve developed and led a national series of workshops on “Facilitating Difficult Conversations Across Lines of Difference.”

In one of our text studies, we reflect on two models of leadership drawn from Torah: Moses, who speaks prophetic truth and demands justice, and Aaron, who pursues peace and reconciliation. Both are holy roles.

Sometimes a rabbi must lead like Moses — speaking with moral clarity and drawing clear boundaries. In those moments, we act as advocates externally and create internal spaces where shared commitments can be affirmed. That work matters: naming what belongs in our spiritual homes helps people understand a specific community’s values and decide how they wish to engage. This is especially effective in larger communities with many places to belong.

Sometimes a rabbi must lead like Aaron — listening deeply, staying present with people in their pain, and working to keep the community from shattering. In smaller or less-resourced communities, where affinity is simply being Jewish together, a rabbi may see this as the only way forward.

The rabbinate, at its best, holds both instincts at once: the courage to stand firm and the compassion to keep everyone in the room. Increasingly, rabbis are learning from the fields of dialogue, mediation, and facilitation how to create communities where disagreement can coexist with dignity, and conflict can become connection.

Speaking with clarity matters; so does holding together and avoiding public litmus tests. In a time when few know how, we clergy are called to try. Our tradition, and good leadership practice, tells us how.

Humility reminds us that no one holds the whole truth. Empathy seeks understanding without demanding agreement. Curiosity keeps us open when it would be easier to armor up and fight.

These practices don’t erase difference; they make relationship possible within it.

The letter that so many rabbis signed is, at heart, a call to defend the Jewish future. But the Jewish future will not be defended by uniformity. It will be defended by the strength of our relationships.

By rabbis and communities who can stay in dialogue even when we disagree. By the courage to speak and the humility to listen. By the ability to say: I love Israel. I oppose antisemitism. And I also see this moment differently.

To the rabbis who signed the letter: your conviction matters.

To the rabbis who didn’t: your restraint and care for your communities matter too.

To the Jewish public watching: know that every one of these leaders is trying, in their own way, to serve the Jewish people with integrity and heart.

Let’s support rabbis — all rabbis — who are carrying impossible burdens on behalf of us all.

If we truly want to defend the Jewish future, we must resist dividing ourselves into pieces. The real work — the holy work — is learning how to stay in community, even when we don’t agree on the same sentence to sign.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.