Like millions of New Yorkers, David Vyorst grew up worshiping the Knicks.

His basketball gods were named Dave DeBusschere, Bill Bradley, Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, Walt Frazier and Willis Reed. His temple was Madison Square Garden.

When Vyorst’s father spoke reverently of Nat Holman, he “thought it was just some guy my dad was babbling about.”

Years later, Vyorst learned that Holman was the legendary “Mr. Basketball,” a star college player in the 1920s who coached the City College of New York to an NCAA championship in 1950.

He also learned that the forebears of Frazier and Reed were men named Leo Gottlieb, Ralph Kaplowitz and Ossie Schectman, who were on the nearly- all-Jewish starting team for the Knicks when they debuted in 1946.

“People don’t talk about it, but Jewish people played a pivotal role in the development of basketball,” Vyorst says.

But they’ll soon hear about it if Vyorst, 42, has his way.

A Washington-based communications specialist, Vyorst is producing a new documentary film, “The First Basket.” It’s a meditation on Jews’ early participation in — and later exodus from — basketball, and how that journey mirrors the American Jewish experience in the 20th century.

“How Jews got involved in basketball is only half the story,” says Jeffrey Gurock, a Yeshiva University history professor who appears in the film. “The other part is the conflict of Jewish identity and sports.”

“The First Basket” will have a world premier of sorts at the Center for Jewish History in New York on June 3, when Vyorst will show a 10-minute trailer for the film.

Sponsored by the museum’s American Jewish Historical Society, the event will function as a fund-raiser for “The First Basket.” It will feature an auction of Knicks items and speakers such as Aviva Kempner, who directed the award-winning “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg.”

The film’s executive producer, Vyorst has raised about $40,000 in private contributions, including a $10,000 National Endowment for the Humanities grant. He needs $250,000 to complete the project in time for planned distribution in the spring of 2004.

Vyorst recently wrapped pre-production, which took him to Inverry Bagel near Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., where every month the South Florida Basketball Fraternity gathers to nosh and kibbitz.

The group includes Schectman, who scored the first basket in professional basketball on Nov. 1, 1946, when the Knicks beat the Toronto Huskies 68-66. The game marked the debut of the Basketball Association of America, the precursor to the National Basketball Association.

Other Jewish hoops pioneers whom Vyorst filmed at their monthly meeting included Max Cohn, Nat Frankel, Sid Gerchick, Meyer Goldman, Manny Kaplan, Solomon “Bud” Schwartz, Jack Silverman and Sy Rose.

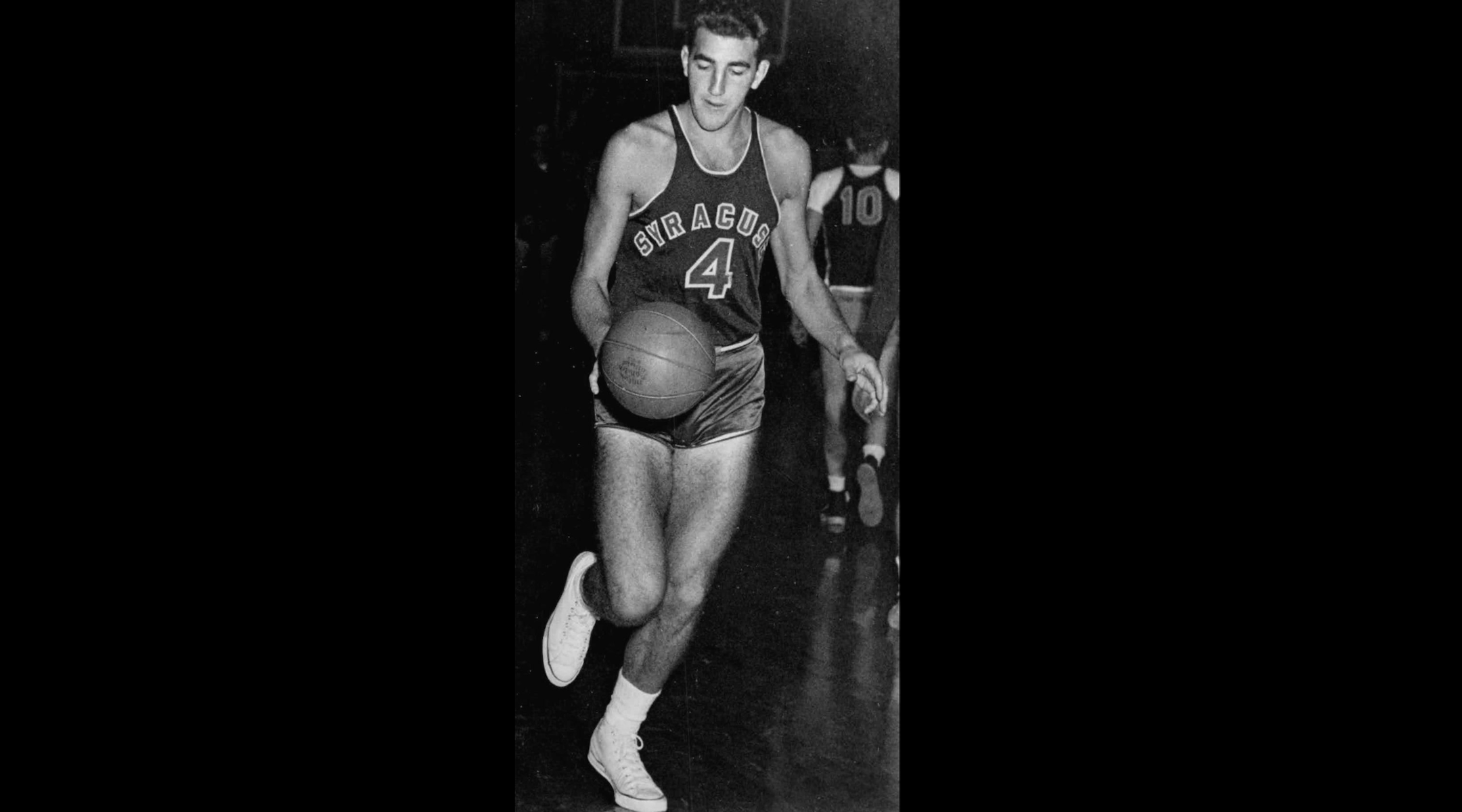

A half century ago they were part of a much bigger brotherhood, which included players like Brooms Abramovic, Jerry Fleishman, Hank Rosenstein, Dolph Schayes and Max Zaslofsky.

The landscape of the floorboards differed vastly from today. There are no Jews in the NBA today, as the Jewish presence in the league ended a few years ago with the retirement of Danny Schayes, son of Hall of Famer Dolph Schayes.

Back then, though, there were no superstars dominating the game like Michael Jordan, Shaquille O’Neill, Magic Johnson or Larry Bird.

When the Knicks first played, “it was more of a team game” with players applying full-court defense, passing rather than dribbling and driving, then relying on the set shot rather than layups, Vyorst says.

“The ball never hit the ground,” he says. “It was like ballet.”

If Jewish-flavored basketball was a kind of dance, it was a distinctly urban movement, Zurock says.

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, the immigrant Jews packed into areas such as New York’s Lower East Side had no place to play baseball or football, he says.

Jews played stickball in the streets, attended immigrant aid houses and joined groups such as the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. These groups promoted “good sports” — such as basketball, then newly invented — rather than violent sports such as boxing, which did attract some Jews.

“Metaphorically, basketball was like a sweatshop,” Zurock says — “you needed people together to produce.”

In the early part of the 20th century, some Jewish leaders such as Rabbi Mordechai Kaplan, founder of the Reconstructionist movement, hoped basketball would effect a kind of “crossover dribble,” enticing young Jews from the YMHA and Jewish community centers into the synagogue.

“Did those who came to play ever end up staying to pray? Some did, but the best athletes did not,” Gurock says.

Meanwhile, institutions run by Jewish secularists and socialists also competed for basketball talent.

As Jews moved from Manhattan to the outer boroughs of the Bronx and Brooklyn, they carried the sport into public schools and city colleges.

Semi-pro leagues began forming, and teams with a Jewish spin barnstormed the country. They featured names like the South Philadelphia Hebrew All-Stars, or SPHAs, whose logo was in Hebrew.

After World War II, however, the game began shifting dramatically. Perhaps the greatest force was the postwar migration of Jews to the suburbs, where they found greater affluence and met growing social acceptance in country clubs and in the professions.

African Americans moved into the city and made inroads into the game.

“The Jewish decline in basketball was a metaphor for the Jewish advancement in culture,” Gurock says.

Then, in 1951, a point-shaving scandal engulfed CCNY and tarnished college basketball. Looking at the half-black, half-Jewish team, a Kentucky coach remarked that it was a scandal of “niggers and Jews.”

Many colleges cut back their programs, and the collegiate game did not rebound for years.

But pro ball filled the gap. Lawyer Maurice Podoloff led the first pro league, and oversaw its merger with a semi-pro Midwest league called the NBA in 1949.

This past winter Vyorst was walking in Manhattan in sub-zero temperatures early one morning when he spotted some young black men at a playground shooting baskets despite the cold.

The sight reminded him of how he grew up dreaming of playing for the Knicks, before life took him in a different direction.

“My mom used to say, ‘There are lots of doctors who play basketball on the weekends,’ ” he recalls.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.