(JTA) — It has been a trying week and a half for Beejhy Barhany.

Her Israeli-Ethiopian fusion restaurant, Tsion Cafe, had already been struggling to make ends meet after months of closure due to the pandemic.

Then the protests over the death of George Floyd swept through the city, bringing up difficult emotions for Barhany, 44, who was born in Ethiopia and raised in Israel.

In a way, the two felt similar.

“COVID-19 is a disease, is a virus. Police brutality and racism is a disease that we have to eradicate,” she said. “So they go hand in hand together, so we are struggling in restaurant business, but for me it is very important to be heard and demonstrate.”

On Sunday, she did just that as she headed to a local protest with her husband and their two children. Wearing masks, the family marched for hours through the streets of Manhattan’s Harlem neighborhood.

We spoke with Barhany and other Jews who attended protests following the death of George Floyd, a black man who was killed in police custody in Minnesota on Memorial Day.

Here are their stories.

A Harlem restaurant owner and her daughter feel empowered

Beejhy Barhany with her daughter Alem, son Berhan Ori and husband Padmore John. (Courtesy of Barhany)

“As a black woman, a wife, a mother, a sister — I wanted to showcase my support and be there to stop this police brutality against the black men and black people period. It has to come to an end,” Barhany said.

Barhany, who is involved with the Ethiopian Jewish community in New York, said other community members joined protests in their neighborhoods.

“Being black, Jewish, we’re a part of that package, so we have to be there no matter what,” she said.

Her daughter, Alem John, feels the same way. It was only the 14-year-old’s second time attending a protest.

“It was very moving,” John said. “It was very powerful, to be with a lot of people that [thought] we should be treated equal, we should not be treated less than. It was an experience I’ve never really felt before.”

Marching for racial justice made her reflect on both her identity as a black person and as a Jew.

“Mostly when I was at the protest, I was thinking about my black identity and how I should be treated as a human being no matter what I am. So that’s what I was focusing on,” she said. “But I was honestly thinking about [my Jewish identity] as well. I’m also a black, Jewish girl, so I’m just seen as less than. I’m a black Jewish girl in America.”

A Persian Jewish millennial starts conversations about race in her community

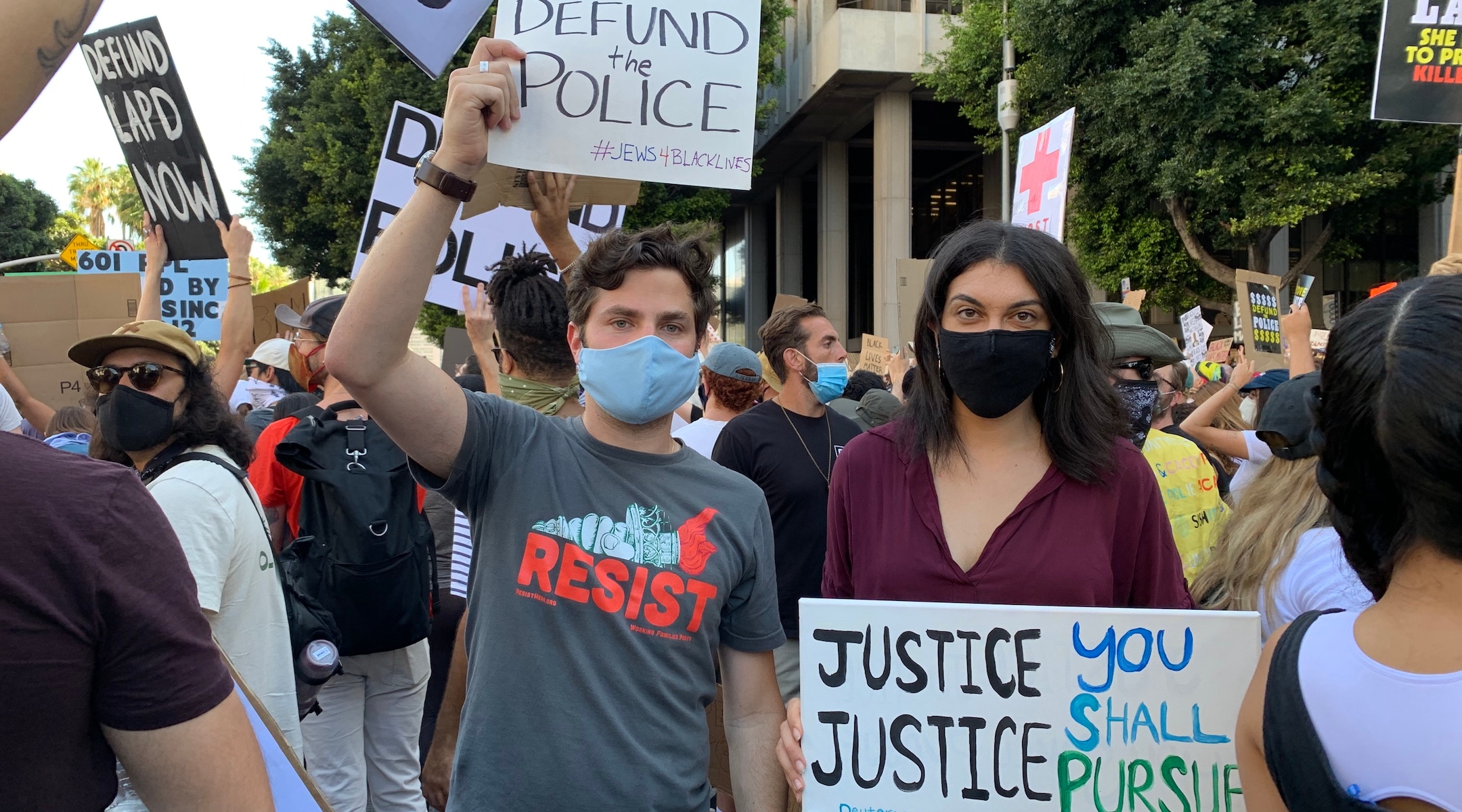

Rachel Sumekh, right, marches in Los Angeles with David Bocarsly, June 3, 2020. (Courtesy of Sumekh)

Rachel Sumekh wasn’t happy with some of the things she was hearing in Los Angeles’ close-knit Iranian Jewish community about the local protests following Floyd’s death.

For some, the focus on ending racism against black people wasn’t compelling. Others took issue with a platform issued in 2016 by the the Movement for Black Lives coalition group that accuses Israel of committing “genocide” against the Palestinians.

“Many people believe that we should say ‘All Lives Matter’ or believe that Israel is the reason why we shouldn’t show up right now. And I know that on behalf of myself and many other Iranian American Jews, that is not true,” said Sumekh, the 28-year-old founder of Swipe Out Hunger, a nonprofit seeking to end hunger among college students.

“We understand the urgency of the moment and stand against police brutality and white supremacy, and silence is not OK right now,” she said.

Sumekh says many who oppose the protests in her community are focused on the fact that some buildings had been vandalized or looted, including synagogues and shops owned by community members.

Though Sumekh isn’t happy about the vandalism, she wanted to return the focus to what she views as the most important issue: racism. On Monday, she and four other young Iranian Jews went to Santa Monica to help clean up after the damage.

“Many people in our community have been concerned about the damage done to property and we don’t want that to be the distraction here,” she said. “People have told me that ‘How can you stand for this when our buildings are being burned down?’ And when someone tells me that I say, ‘Tell me which building and I’ll show up to clean it.’”

On Wednesday, Sumekh and some friends released a statement of solidarity with the black community titled “Iranian American Jews for Racial Justice.” Sumekh also attended a Black Lives Matter protest on Wednesday. She said she is inspired by her own family, which had to flee their home country amid anti-Semitic persecution.

“It’s my parents who went through this — being beat up for being Jewish, having to flee their country at moments’ notice, having to be subject to being second-class citizens and living in constant fear of the government,” she said.

“How can we hear those stories and not want to be able to say to our grandchildren or our children that when we witnessed the same injustice in our country, this place that gave us a home, that we don’t have those same stories of speaking out and fighting that injustice?”

A black Jewish filmmaker finds community in Boston

Rebecca Pierce joined a protest in Boston, May 31, 2020. (Courtesy of Pierce)

Rebecca Pierce was initially hesitant to go to a protest. Though the 29-year-old filmmaker is an outspoken activist on a number of issues, she has been living in Boston for less than a year and does not know many people in the area.

“It’s not my hometown. Nobody really knows me here,” said Pierce, a San Francisco native and a fellow at Harvard Divinity School. “For safety, you generally don’t want to go to a protest in a place you’re not familiar with, where there’s no one who knows you.”

But when a few members of her program asked her to join a march on Sunday, Pierce, who is black and Jewish, decided to do it. Still, she took precautions.

“I have a lot of experience protesting in many different countries, and you sort of know that the violence tends to happen — the really brutal police repression tends to come up at the end of things when there’s less control by the organizers,” she said. “I was worried going into it and definitely picked a strategic time to leave.”

Pierce later learned that law enforcement used tear gas on protesters later in the day.

She felt empowered attending the protest, which started out in the historically black neighborhood of Roxbury.

“There’s nothing that can make you feel better from the loss and grief that’s happening in this moment, but it was very important and healing for me to be in community, especially with a lot of other black people,” she said.

Pierce thought about her Jewish identity, too.

“I was thinking a lot about my black ancestors and my Jewish ancestors who passed on to me these legacies of resistance,” she said. “And this moment, and a lot of moments in my life, is a culmination of both those things.”

A Jewish religious leader takes a stand outside a Washington church

Maharat Ruth Friedman participates in a solidarity rally outside St. John’s Episcopal Church in Washington, June 2, 2020. (Courtesy of Friedman)

Maharat Ruth Friedman was hesitant to get involved with the protests because she wanted to maintain social distance and, as a white person, she was still figuring out the best way to offer support.

But when Friedman, 35, learned that police had used force to clear peaceful protesters from St. John’s Episcopal Church so that President Donald Trump could have a photo taken there on Monday, something changed.

“I really had a change of heart and felt that this was such an outrage and such a desecration of such a holy religious place and holy religious atmosphere and holy religious people, that it was imperative that I show my support,” said Friedman, a member of the clergy at Ohev Sholom-The National Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation in Washington, D.C.

The following day, she joined a prayer vigil with 20 clergy from different faiths as protesters passed by the church. Her colleague from Ohev Sholom, Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld, joined her, as did Rabbis Hannah Goldstein and Jonathan Roos of Temple Sinai, a Reform congregation.

“I felt proud to be there as a representative of the Jewish community, and I felt that it was important that we were there. And I think our presence was felt and appreciated,” she said.

On a personal level, Friedman, who hasn’t attended any in-person gatherings since her synagogue closed in the middle of March, felt energized by the event.

“It felt powerful and it felt good to be around people who really care about something and are passionately fighting for something very important,” she said.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.