LOS ANGELES (JTA) — When Tom Tugend was 13 years old, he received news not uncommon for a teenager: His family was moving. His father, a respected physician, had taken a new job.

During the taxi ride to the airport, Tugend looked out at his beloved hometown. All around him were trees and poles covered with massive swastika banners.

The date was April 20, 1939, and Berlin was celebrating Adolf Hitler’s 50th birthday.

“Gee, I mean, they may not like the Jews, but it’s very nice of them to give us such a nice sendoff,” Tugend recalled with a laugh this month from his home here.

Now 96, Tugend is still offering shrewd takes on current events as a seasoned journalist who has written for countless Jewish publications — including The Jerusalem Post, the Jewish Chronicle, the Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency — over a seven-decade career in Jewish journalism.

Tugend, whose reporting career began in the U.S. Army, has contributed to JTA as a West Coast correspondent since at least 1989, and still writes about Israeli film, Jewish theater in Los Angeles and other stories related to the entertainment industry and Hollywood.

“You still get a certain kick in seeing your byline,” Tugend said. Plus, he added, there’s the benefit of free tickets to premieres –– a cheap date for him and Rachel, his wife of 64 years.

For an award-winning journalist, Tugend has quite a story of his own.

“There’s not going to be a war”

Tugend was born in 1925, eight years before Hitler came to power in Germany. He grew up in a Jewish community and devoted much of his attention to his love of soccer.

“Unless you lived up to the stereotype of the hook nose and horns growing out of your forehead, you weren’t bothered,” he said.

Tugend’s father, Gustav Tugendreich, was more alarmed by the rapidly changing outlook for Jews in Germany.

Tugendreich was an influential pediatrician who has been touted as the “father of public infant welfare” in Germany, according to the International Journal of Epidemiology. In 1911, Tugendreich turned down the directorship of an infant mortality center because the role would have required him to renounce Judaism.

Once Hitler came to power, Tugendreich was no longer permitted to treat non-Jewish patients.

“It killed him, not physically, but spiritually, emotionally,” Tugend said.

Tugendreich left for America before the rest of the family, securing a lectureship at Bryn Mawr College in suburban Philadelphia through a loophole in America’s immigration quota system. He wrote letters to his family in Berlin, urging them to take the next boat possible to get out of Europe.

“We all said, ‘Well isn’t that good old Dad, he’s always worried about nothing,’” Tugend said.

Even after Kristallnacht, during which the store of Tugend’s neighbor was smashed, Hitler convinced the German people that there would be no war. In retrospect, Tugend says he and his fellow countrymen were suffering from Stockholm syndrome, wherein victims develop a psychological bond with their captors.

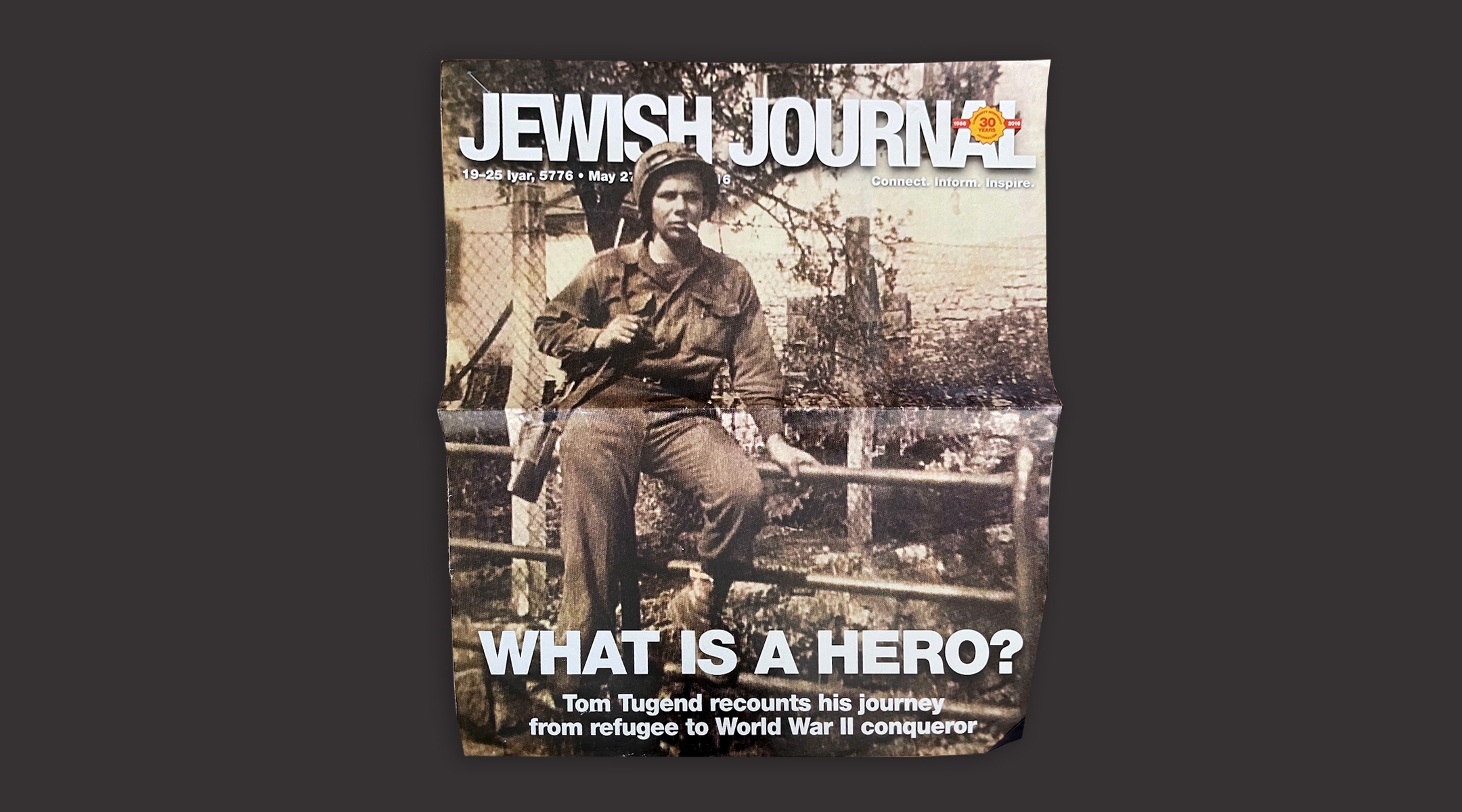

Tom Tugend in April 1946. (Courtesy of Tom Tugend)

Fortunately, the Tugends listened to their father. They left Berlin four months before war broke out.

Upon his arrival in America, Tugend attended a Jewish summer camp and met other children who had seen newsreels and believed war was imminent in Germany.

“I said no, there’s not going to be a war,” he recounted. “I come from there, I know the situation. I can tell you there’s not going to be any war because that’s what all the German papers said.”

Even when he returned home to headlines of Germany’s invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, he was in disbelief.

“I said there must be some mistake,” Tugend recalled. “It can’t be.”

He added, “Obviously if I’d stayed there, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”

A decade of war

The Jewish experience in Europe during the Nazi era is well documented. But what makes Tugend’s story unusual is that for him, acclimation to America was harder than life in Germany.

“I don’t generally talk about it because it goes so counter, it sounds almost disloyal that you say I had a more difficult time initially in the United States than I had in Germany,” Tugend said.

The prejudice was immediate. In eighth grade, Tugend’s class read Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice,” which famously includes Shylock, a Jewish moneylender, as a main character. One of Tugend’s classmates, whom he had considered a friend, raised his hand and asked the teacher, “Wouldn’t you rather buy from an American than a Jew?”

The comment distressed Tugend.

“Here my whole dream was to become a 100% American, and this guy’s saying I can’t be a Jew and an American,” he said.

At 18, Tugend registered for the military draft. Still in high school, he was restless and wanted to get away from home. He was deployed in March 1944.

During his basic training in Florida, Tugend again encountered hostility toward Jews. There was a stereotype that Jews were cowards and draft dodgers, he said. Some of his fellow cadets had never met a Jewish person, and one was genuinely surprised that a Jew could even be in the Army — and that he didn’t have horns.

“I found out, even when the war started, that I was treated better if they thought I was a German than if they thought I was a Jew,” Tugend said. “It’s hard for people now to gauge the extent of antisemitism there was in America.”

At the time of his enlistment, the U.S. Army had just suffered heavy losses. So despite a high score on the Army’s IQ test, Tugend was assigned to the infantry, not intelligence.

“If Einstein had gone in the Army at that time, they would have put him in the infantry,” Tugend joked.

Once his training was complete, Tugend was shipped off to Marseille, where his unit endured a frigid winter in the Vosges Mountains, “freezing our nuts off in foxholes” while helping the 1st French Army fight SS units, he said.

Shortly before the war ended, Tugend’s superiors discovered that he spoke fluent German, and he was sent to southern Germany. There was a theory that some diehard Nazis had remained in each village to organize the resistance to the Allied occupiers. Tugend’s task was to find them.

“Suddenly you couldn’t find a single Nazi,” he said.

Tugend said the assignment came with a jarring power dynamic: Those he interrogated were suddenly deferential to the 19-year-old Jewish soldier at their door.

“I had been a refugee a few years before,” Tugend said. “They kicked me out, they were the masters. And suddenly they couldn’t be nice enough, and couldn’t do enough for us.

“And of course, each one, some of his best friends were Jews,” he added sarcastically.

Tugend returned to the U.S. in March 1946, though not for a long stay. Two years later, still restless, he went to fight in his second war: Israel’s War of Independence.

“Since a Jewish state is established only every 2,000 years, I was afraid I might not be around the next time,” he said.

Tugend served as a squad leader in an Anglo-Saxon (English speaking) anti-tank unit. But there was a problem: The unit didn’t have any anti-tank guns. At least at first.

During a major engagement in the Negev, Tugend’s unit had surrounded an Egyptian troop commanded by the future president of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Czechoslovakia had just sent the Israeli army a shipment of anti-tank guns that were left over from World War II — a welcome delivery for the strapped unit.

There was one catch: The guns had originally been made for Germany, so the barrels were emblazoned with large swastikas.

“If you want an example of complete irony, what is better than a bunch of Jew boys from the Diaspora shooting at the Egyptians with a swastika?” Tugend recalled with a chuckle.

After the war, with Israel established, Tugend returned to California and completed his journalism degree. His education would come in handy almost immediately when a different conflict erupted — in Korea.

Tugend was drafted again in 1950. He feared another combat assignment, but with his journalism degree in hand, Tugend was sent instead to the Presidio of San Francisco, a military base where he spent a year editing a newspaper for the Letterman Army Medical Center.

As he dryly put it, “the only thing more important than killing commies was to put out a newspaper.”

The newspaperman

And then, as Tugend says, he ran out of wars. His stint at the Army paper introduced him to the San Francisco Chronicle, where he would go on to work as a copy boy, obituary writer and court reporter. He also worked on the night desk at the Los Angeles Times.

Tugend said he’d always wanted to be a writer, but thought he didn’t have it in him to be a “serious” writer, like a novelist.

“If I write an 800-word article, I feel like I’ve written ‘War and Peace,’” he quipped, referencing the 600,000-word novel.

Instead, Tugend worked in journalism and communications roles. After the Korean War, he wrote pilot manuals at Boeing, and later enjoyed a 30-year stint at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he worked as a science writer, among other roles.

Beginning in 1964, Tugend also worked part-time for Jewish newspapers, first in Los Angeles and then around the globe. When he retired from UCLA in 1989, Jewish journalism became his primary focus.

Tugend is not religiously observant, but he said he has always felt an attachment to his Judaism.

“I realized when Hitler came to power that whatever happened to the Jews would affect me,” he said.

Lisa Hostein, the longtime former JTA editor in chief and current executive editor of Hadassah Magazine, remembers meeting Tugend on a Jewish press trip to Argentina in 1986.

Hostein has worked with and edited countless reporters, especially in Jewish journalism. She told JTA that Tugend stands out for his professionalism and attention to detail. On foreign trips, she recalled, Tugend would always know what questions to ask high-level officials, and he made sure to get every title and name correct.

“He was always the consummate professional and gentleman,” she said.

Journalism also turned into a family affair. Tugend’s daughter, Alina, is a freelance writer who covers education for The New York Times and other national publications. She said she shares her father’s temperament and his love of speaking with and listening to others.

“I don’t think I consciously thought, ‘Oh, he’s a journalist, that’s what I want to do,’” Alina Tugend, 61, told JTA, recalling that her father frequently brought notes from his day scrawled on yellow paper to the dinner table to share with the family. “It was more being surrounded by people.”

Tugend is a Lifetime Achievement Award recipient from the American Jewish Press Association, and has been honored as well by the Greater Los Angeles Press Club and the Society of Professional Journalists.

So what’s his favorite story that he’s written?

The first that comes to mind is a 2016 piece he wrote for the Jewish Journal about himself. Tugend recounts his story and reflects on his life of service.

“It’s OK if we bullshit each other,” Tugend said, “but maybe we shouldn’t bullshit ourselves.”

Tom Tugend on the cover of The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles, May 2016. (Courtesy of Tom Tugend)

He’s not being facetious. As a veteran, Tugend says he brings an important perspective to journalism. While war is inherently dramatic, Tugend has noticed a tendency in the American media to glorify patriotism. Who better to provide honest reporting about war than those who have lived through it?

“The most overused four-letter word is ‘hero,’” Tugend said before offering a few other similarly overused four-letter words not fit for publication.

Heroism is a topic about which Tugend feels rather passionate. Moral courage, he says, is a very rare characteristic, especially in the context of the Holocaust. His real heroes are those across Europe who saved lives by hiding and protecting Jews.

“Those to me are my only genuine heroes –– those who stood up at the risk of their lives to shield somebody with whom they had no connection,” Tugend said. “You knew that if you were caught, you were dead and probably your family would be killed, and nevertheless to do it because you felt as a human being you had to do it.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.