(JTA) — “This isn’t hell,” Jerry Stahl writes. “This is the Museum of Hell.”

“This” is Auschwitz, and Stahl’s epiphany comes about halfway through his new book “Nein, Nein, Nein!” (Akashic Books), his nonfiction account of a two-week bus tour in 2016 of concentration camps in Poland and Germany.

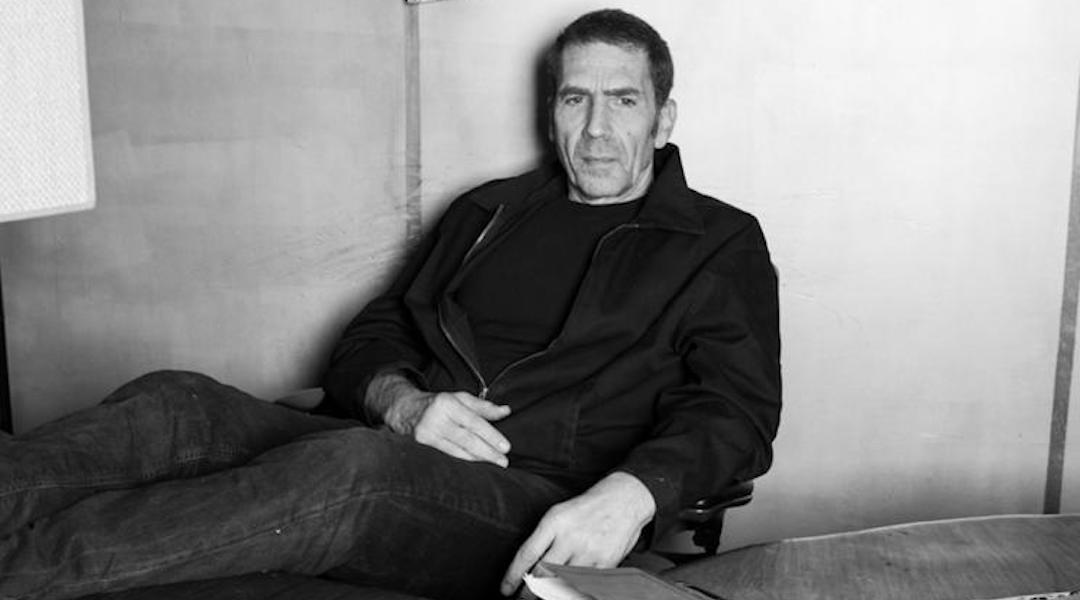

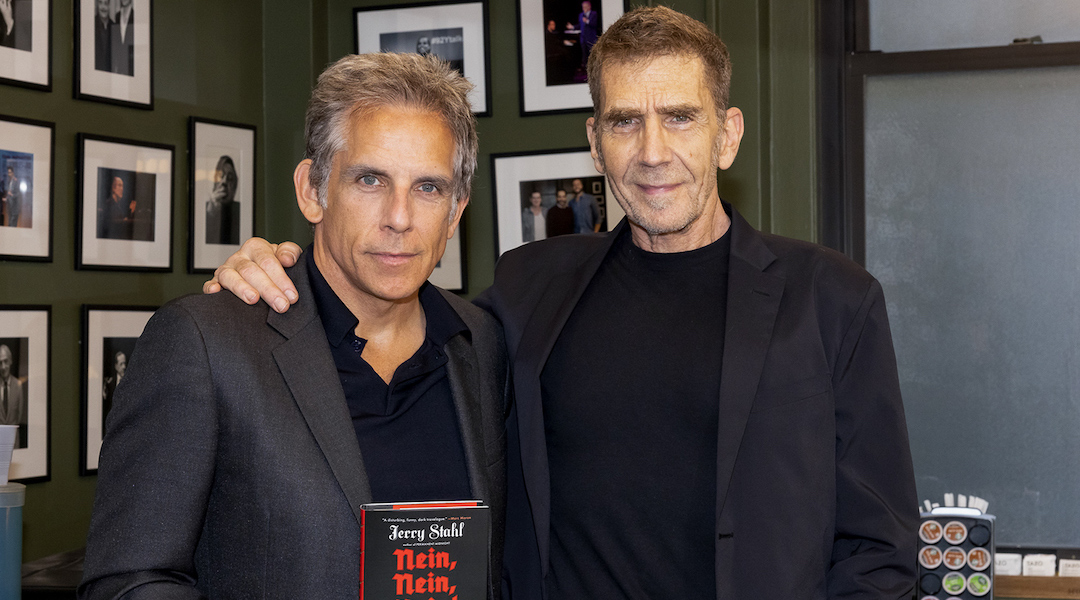

Stahl is no stranger to dark places: A novelist and screenwriter, he is best known for his 1995 memoir, “Permanent Midnight,” a harrowing account of his heroin addiction and the calamity he made of his first marriage and television career in 1980s Hollywood. (Ben Stiller starred as Stahl in the 1998 film adaptation.) In this case, Stahl, 68, is not just one of the few Jews on the guided tour of hell but perhaps the least enthusiastic tourist ever to squeeze into a bus seat: He joined the trip at a low point in his marriage, career and mental and physical health. “Via my group tour,” he writes, “I hoped that I could once more find relief in a situation where feeling miserable was appropriate.”

But while “Nein, Nein, Nein!” is darkly confessional, it is also an exploration of how we remember the Holocaust and whether it is even possible to properly mourn and honor the victims of unspeakable tragedy. He joins the crowds as they stand before the gas chambers, and as they later line up for pizza at the camps’ snack bars. The result is a sort of gonzo travel book about the ways the Holocaust is memorialized, commercialized and trivialized in the countries where it took place.

It is also quite funny, as you might expect from a writer whose credits include “ALF,” “Moonlighting” and “Maron.”

Stahl lives and works in Los Angeles. We spoke via Zoom on June 22.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

New York Jewish Week: You cut so deeply into my own anxieties about the Holocaust. I went to Auschwitz for the first time three years ago after a career doing this Jewish stuff. And, like you, I didn’t know what to do with it. What are you supposed to feel? And if you don’t feel what you think you’re supposed to feel, are you failing the memory of the victims?

Jerry Stahl: That is my book in a nutshell, right there.

What kind of conclusions were you hoping to reach for yourself?

I went for perhaps the most tawdry of reasons, which is I was massively depressed, going through some hard times. I come from a family of depressives and suicides, you know, not to brag. So I had this crazy idea: I want to go somewhere where this massive, just bone-deep sense of despair is justified and appropriate. I went there expecting some lofty, soul-infusing, immense, life-changing experience, because it’s Auschwitz. And what I see are people sitting in the snack bar, eating a slice of pizza and slurping a Fanta. It’s like, well, I went to see humanity and guess what, I saw humanity. So there was a bit of a disconnect between what I might have expected and what I ended up seeing,

Was the tour for you meant to be therapeutic, or were you looking to understand something about the Holocaust?

I was dead center on that spectrum. You know, I never identified particularly as a Jew. I grew up in a neighborhood in Pittsburgh where I was pretty much the only Jew and got routinely beaten up for killing Jesus, which you know, I must have done in a blackout at the age of 5. But as my grandfather once said — he was a Polish fella who came over here to escape the czar’s army — “If you ever forget you’re a Jew, a gentile will remind you.” So it wasn’t therapeutic as such. I just wanted to plunge into the heart of darkness, to use a really unenviable cliche.

I see it as a piece with your other writing, where you go places where other people may not want to go, whether it is addiction, or mental illness.

Yeah, somewhere no one wants to go, but I drag the reader along. And on some level you like to think it’s relatable.

You describe your fellow travelers — the tough-guy older Jew Shlomo, a couple from Texas, the older gay couple. Why were they on a tour of death camps? I know even when Jews go to the camps, they usually try to balance it with something leisurely and redemptive. You know, stop in Paris and make your way to Krakow. But how was this tour marketed? What do you think your busmates were doing on it?

It’s a world I knew nothing about. But for a certain kind of non-rich person who wants to travel, bus tours are a thing. For some of them it was less about the Holocaust than the fact that well, we just finished the Finger Lakes and we’re gonna go to Ireland after this, and it just so happens that this one is Eastern Europe. For another group of people, I think they had never seen a Jew before and because they watch the History Channel, they were kind of curious. You know, there’s a scene in the book where we went around a table and everybody had to say why they went on this tour. There was a lot of “Oh, I saw ‘Schindler’s List’” or “I’ve always admired the Jewish people.” And by the way, I say that not in judgment, I ended up kind of loving these people, but it was clearly massively uncomfortable for me.

I’m starting to feel guilty. I guess I did the same thing when I visited the American Southwest and toured a Navajo reservation: the outsider coming to gawk a little bit at their tragedy.

Right? But what is the appropriate response? I mean, part of me wants to kind of hurl myself on the ground and start keening, wailing and rending my hair. But another part is, well, here we are, and I need to find the men’s room.

Jerry Stahl is the author of “Nein, Nein, Nein!: One Man’s Tale of Depression, Psychic Torment, and a Bus Tour of the Holocaust.” (Akashic Books)

Which is a scene in your book. At one point you recommend Tadeusz Borowski’s “This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen,” a collection of short stories based on his time in the camps. Did you see yourself writing in a tradition of using humor to confront the horrors of genocide? Did you ever worry that a book about the Holocaust that included comedic moments would be seen as inappropriate?

How could I not worry about that? And the line I had to walk was to show complete respect for what happened and where it happened, but at the same time, what it has become now. And that is a guided tour of the worst thing that ever happened to us. And, of course, I still worry that it will be misinterpreted. But I like to think that anybody who reads the book will understand the human condition on some level is inherently comedic and you’re dealing with these ridiculous moments. I mean, people putting their foot up on a tombstone in Krakow of Rabbi Moses Isserles and tying their shoe. Is that comedic or do you want to punch yourself in the face?

A great Jewish American novelist and playwright, who I really always loved and even imitated, Bruce J. Friedman, once wrote that if you write a sentence that makes you squirm, keep going. And on some level, I squirmed my way through this book, because, at the risk of sounding pretentious, the artists I love are the ones who say the unsayable. Because that is what I want to read.

Speaking of which, you also write about how the Holocaust and Nazism has been fetishized, either in pornographic Israeli comic books, known as stalags, based on Nazi themes, or in soft-core enterprises like the 1975 cult movie “Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS.” Even the title of the book is a throwback to a scene in your earlier memoir, “Permanent Midnight,” in which you write about your “full blown fascination with Holocaust porn.” Why was it important for you to go there?

I mean, look at the Proud Boys with their swastikas chanting “Jews will not replace us” at Charlottesville and everywhere since. I don’t know those guys, but I would guess on some level there is a sexual component that I just always found fascinating and grotesque, and on some level profoundly human. This is a boomer reference that may mean nothing to you, but “Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS” was filmed on the set of “Hogan’s Heroes” [the 1960s sitcom set in a Nazi prisoner of war camp] on weekends. The studio even said, “You can have it for X amount of money and you can burn it down because we got to get rid of it anyway.” It’s the intersection of pop culture and the depraved.

You dwell on the idea that you’re visiting both a concentration camp and a museum of a concentration camp, and it’s going to have the entire tourist apparatus, like restaurants and gift shops. Did you conclude that maintaining the camps serves a purpose, or does the commercialization undercut really any good that can come from this?

That’s kind of a moving target. On some level, I think they should just fence it all off, like a Superfund site, and people can drive by or walk by and look at it from afar. That’s one part of the spectrum. On the other hand, there is no denying that, you know, kind of tottering through Auschwitz in a line of people and looking at a two-ton ball of hair behind the glass is absolutely soul-crushing. Because, as is often the case, in art and life, it’s the specifics that will really bring it home. So that’s valuable. Far be it for me to judge somebody who wants a slice of pizza or a Fanta after seeing what they see in the ovens, but I wasn’t prepared for it. That’s who we are as a species, and it’s not for me to judge or think I’m any better. But it was both uncomfortable and unspeakable, and wholly human and wholly surprising.

Did you have a particular interest in the Holocaust before this project?

In a litany of things I think you have to be to be Jewish I was, you know, I guess I can’t escape it in some ways. So I’ve never really asked myself, you know, am I fascinated by it. Are you?

Actor and director Ben Stiller, left, who played Jerry Stahl in the film “Permanent Midnight,” spoke with the author about his new book at the 92nd Street Y in New York, June 12, 2022. (Michael Priest Photography/92NY)

I would say sometimes I get burned out on it. And wonder if we view contemporary Jewish life too much through the lens of persecution, instead of focusing on maybe what’s, you know, delightful and upbeat and spiritual about being Jewish.

There’s this theory of the epigenetic quality of anxiety and dread and trauma that is sort of baked into every young Jew upon birth, like our version of original sin.

When did you first encounter the Holocaust? When did it become something that you were aware of and wrestled with?

It wasn’t discussed much in our home. My father was an immigrant who came over at 10 by himself from Lithuania, and his father had been apparently killed in a pogrom when [my father] was 2, on the Russian-Lithuanian border. But these are things I found out later. And the older I get, the more inescapable are questions like, “How could this happen?” And then by the time I’m done with all my research, and living and writing this book, it’s like, “How can it not happen more often?” Because on some level, it is always happening, which is how the book ends, you know, the axe is always falling, enjoy the time between Holocausts because look where we are now. Did you think you would live to see this when, courtesy of our ex-president, we would have to worry about this again?

How did you prepare for the trip? Did you dive deep into Holocaust history?

If I keeled over today, the paramedics who came into my house would find these shelves upon shelves of books about Nazis, and they would either think I was a Nazi or a scholar of Nazism. But there is no doubt that I have been obsessive. I wanted to plunge in.

What part of you does it touch that you find yourself returning to it as a subject?

I think it goes to the core situation of being Jewish whether you want it to be or not. I don’t know if this happened to you: You’re having breakfast in Poland somewhere, and there is some sausage-gobbling 97-year-old giving you stink eye over the buffet table, and you can’t help but think, is he looking at me? Does he know? When he was 19, was he bayonetting Jewish babies for fun with his buddies? Because that is the reality: Very few of these guys paid a price. Look at IG Farben, running slave camps. Do bar mitzvah boys care that Hugo Boss designed SS uniforms? You can drive yourself nuts, pursuing it to the nth degree, and maybe I have.

In a way — and I haven’t talked about this — but this was a pandemic book as well. You know, because what better excuse to be isolated, depressed and self-obsessed?

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.