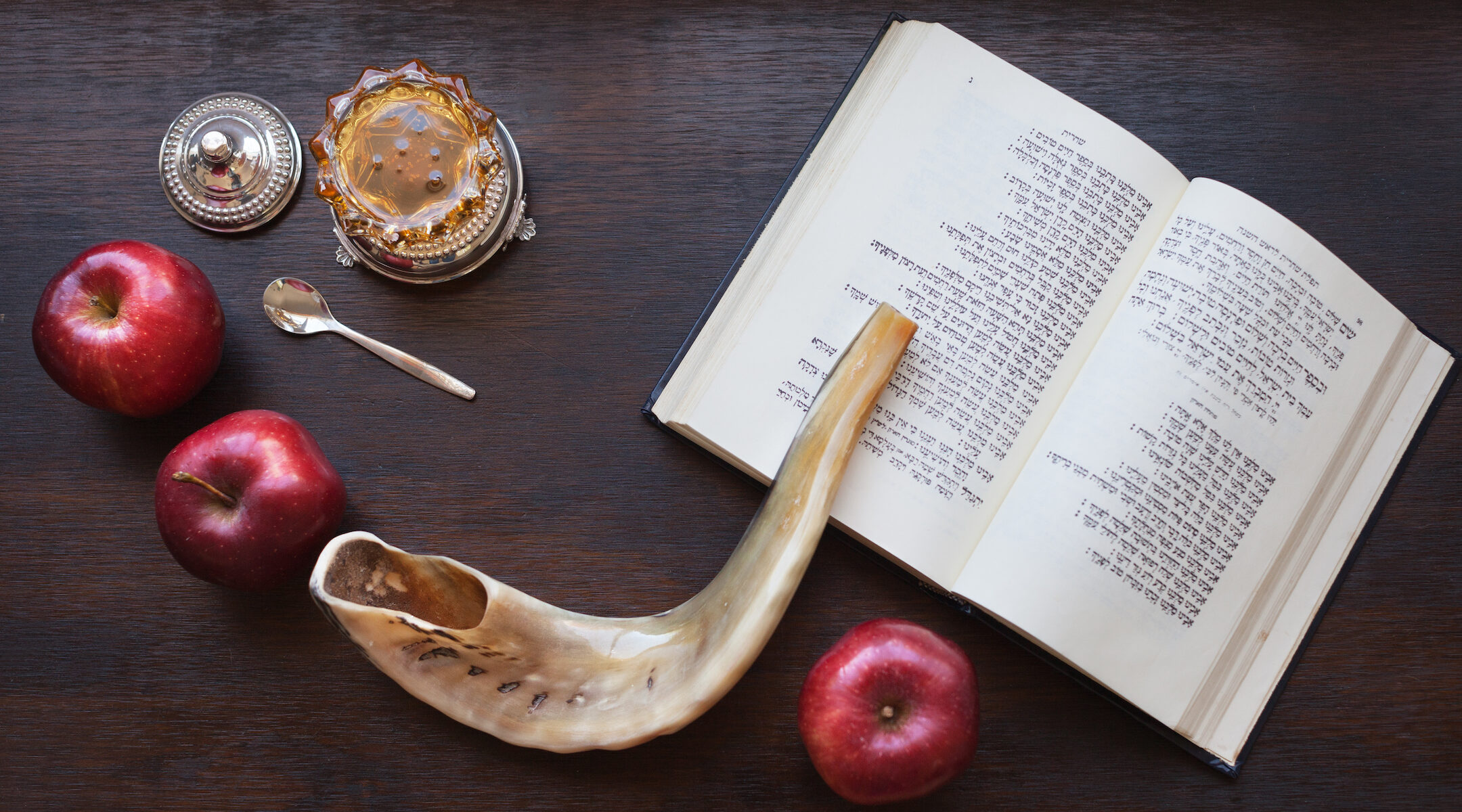

(JTA) — As Jews across the United States and the world gather for the High Holidays beginning at sundown this Sunday, there are sure to be a handful of common themes emanating from the pulpit.

This year marks a third High Holiday season under the shadow of COVID-19. The war in Ukraine has raged for seven months. The United Kingdom’s long-reigning monarch recently died 70 years after being crowned.

Suffice to say, there is no shortage of sermon fodder as the Jewish community ushers in a new Jewish year, 5783.

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency reached out to a geographically and denominationally diverse range of rabbis to ask for a glimpse of the messages they are sharing with their communities during these High Holidays.

Their responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Are you a rabbi with a message you’d like JTA readers to hear? Please reach out.

“The only antidote to fear is true faith”

Rabbi Rachel Isaacs, Beth Israel Congregation, Waterville, Maine

Fear can protect us and bring us to prayer in a spirit of healthy humility. However, when fear becomes a generalized anxiety that prevents us from enjoying and recognizing blessing around us, when fear causes us to live in constant suspicion of our neighbors and the purity of their intentions, when terror makes the world seem irredeemably dark — it becomes something dangerous.

I do believe that there is another way — and not surprisingly — I believe the only antidote to that kind of fear is true faith. Not religious behavioralism, not religious judgment, but true faith in the goodness of God and Divine creation.

Rav Nachman of Breslov, writes famously in his book “Likutei Halachot” (interestingly enough in the context of the laws of shaving):

The core idea in the service of God is that a person should have no fear, as our rabbis (zichronam livrachah) taught us that in this world a person needs to walk on a very narrow bridge, and the most important thing is that this person should have no fear. The most important thing as a person is strengthening himself to walk across this narrow bridge in peace and without fear is the holy faith.

The most important thing as a person is strengthening herself to walk across this narrow bridge in peace and without fear is the holy faith. Faith in Judaism isn’t about submission or obedience to dogma. Emunah, or faith, means faithfulness — which is to say, staying in relationship with God and one another through the vicissitudes of life and the instability of our individual, fleeting emotions. What holds us steady through the creaking, dilapidated, shaking narrow bridge, is the fact that we are holding fast to one another and the God who created us, the God who created us to live in eternal community and to enjoy our fleeting days on this earth. This is how we suspend ourselves in space — through community and relationships we refuse to relinquish despite the disagreements, pain and misunderstandings that will inevitably emerge.

“What if our world was shattered and no one cared?”

Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker, Temple Emanuel, Winston-Salem, North Carolina

When I was being held hostage on Jan. 15, I didn’t know about all of the vigils and all of love and all of the fear. I didn’t know until after we escaped that y’all were with us. So many of you were with us that day in Colleyville — waiting, hoping, praying, and ultimately rejoicing that we made it out alive.

Our rabbis teach: “Kol Yisrael arevim zeh bah zeh,” that all Jews are responsible for one another. The outpouring of emotion that you shared during our ordeal and in the aftermath embodied this principle. It overwhelmed us in the best of ways. I was eternally grateful for all the support and thought a lot about how it would feel to go through something like that and be met with silence. What if our world was shattered and no one cared?

The idea that we are all responsible for each other means that no one should ever have to feel that way. Being responsible for each other means that when we’re a part of a Jewish community that we never have to question whether we belong. Within our fractured communities, we often fall short of this ideal.

Elul is a time for personal and communal reflection. It’s a time for change. We seek healing in our lives and healing for our communities. Start with being responsible for each other. Live this value. We need you!

“Let us try again”

Rabbi Mira Rivera, Ammud Jews of Color Torah Academy

Jewish tradition gifted us with the month of Elul just before Yamim Noraim, the Days of Awe. For a month we were invited into fields of memory for an accounting of the soul. The braver among us crossed minefields to go face to face with those whom we have wronged, or those who wronged us.

The past, the flickering or frozen fields on screen and in our mind’s eye, was where we ran away from grief towards relief. Do we remember our essential workers? It seems so long ago. We thought we were tired. THEY were tired. Essential workers are still tired.

Remember the campaigns against intellectualism, against science, against breaking the silence? They are still happening. Some of us flee even in our dreams, chased we are by injustices committed on us, or by us.

No cinematic slow motion here. No hair-swinging, sunlit-dappled, Muzak-underscored romp across the golden screen, but a national marathon where mouths open to an endless scream, but sometimes the sound cuts out.

I’m sorry. Please forgive me. Let me try again. Let us try again with eyes, ears and arms wide open. Enter Tishrei, the month of new beginnings, return and atonement for our people. Oh, to be in Awe again!

“How must we learn and relearn to be close to one another?”

Rabbi Claudia Kreiman, Temple Beth Zion, Brookline, Massachusetts

For the past two and a half years, many of our relationships and interactions have centered on social distancing. Even during the hardest times of the pandemic, we found new ways to make connections, both spiritually and communally: drive-by birthday celebrations, morning minyans on Zoom, sharing messages of hope in our windows and on our sidewalks, and more.

Now, as we “come back” as a community to celebrate these High Holidays and to be close to each other, both physically and spiritually, we will reflect together on what it means to be close. Close to each other, close to God, close to our synagogue community, close and fully present in the world. After the last two and a half years, how must we learn and relearn to be close to one another? How do we find closeness to God? How do we connect from a place of truth to find God’s presence in our lives?

The verse that is guiding us is from Psalm 145, verse 18: “Karov Hashem l’chol korav, l’chol asher yikrau’hu v’emet” — Adonai is near to all who call, to all who call sincerely.

The Hebrew word “karov,” which means near or close, is also related to the word “korban,” which means sacrifice or offering. In the ways that we come close, we also bring our own offerings to each other, to our communities, and to our society. During the High Holidays and this new year, we will reflect on the ways we do this: It is a call to show up, to find truth in the world, to bring justice and healing to this broken world. The High Holidays are such a gift of new possibilities, of change, of starting anew, of reflecting, of reconnecting.

As we learn and relearn how to be close to one another this season, may we also learn and relearn how to bring our offerings to our communities. May it be a sweet and new year, a year where each and everyone can show up in it in the best ways possible to live meaningfully and to make this world a better place.

“Our society needs to learn to listen”

Rabbi Marc Katz, Temple Ner Tamid, Bloomfield, New Jersey

Our current moment is living through a new kind of idolatry, one as pernicious and dangerous as that found in the Torah.

Idolatry is magnifying something other than God as the ultimate. Our ancestors did it with statues of stone and gold. Throughout history, idolatry has manifested in a myriad of ways: in exalting money, power, prestige, social standing. But I fear that we are at a point in our history where more than anything, the modern-day idolatry is found primarily in making our own ideologies into a kind of God. And this is true wherever you fall on the political spectrum.

There are plenty of reasons why this has happened. Technology creates echo chambers where your own ideas are reinforced. We have grown unaccustomed to discomfort, a key ingredient to growth and thoughtful discourse. In the tension between our private wants and the public good, our society has turned toward the individual and away from the collective. Politics has replaced staples like religion as the convener of community and the central gathering point of people’s lives. And when politics function more like social clubs, where one gains entry by proving their fealty to a set of moral and legal prescriptions for our county, then policy positions are viewed as referenda on the integrity and character of the person holding them.

To live an ethical life, one needs a certain degree of humility. He or she needs to understand that moral living is a fallible enterprise. On the one hand, we have to have rules. We have to make policy. We have to choose sides. Otherwise we will be crippled by our own inability to act. Yet, in making them, we cannot be so wed to our own regulations and requirements that we are unable to question them and pivot when we err.

More than anything, our society needs to learn to listen, to digest, to think deeply, and to be willing to compromise. None of us are so smart as to have all the answers, and even when we do think we are right, there are plenty of reasons to compromise that too for some greater good.

“This will be a time for all of us to think about what is important”

Rabbi Rachel Ain, Sutton Place Synagogue, New York, New York

The High Holidays are a unique opportunity.

Over the course of the year, week in and week out, rabbis are often asked to respond to the news of the day and what Jewish tradition might say about it. So in thinking about the holidays this year and what my congregants needed to hear, I decided that I wanted to focus on the theme of wisdom.

At a time where we often only get information in soundbites, I want to inspire those listening to realize that to approach life today with the many inputs coming at us, the holidays can be a time to think and listen and learn what is important to them as they give themselves the chance to press pause on the busy-ness of life and then re-start with the ability to make new commitments and improve on the past.

So using Jewish tradition as the backdrop, my hope is to show that whether it is the wisdom within each of us, the wisdom learned from others, both with us and those who have passed, the wisdom of engaging with Israel, and even the wisdom of fear and failure, this will be a time for all of us to think about what is important.

There is no question that the past two and a half years have changed us and our world, not only because of the pandemic but because of the many complex issues that have been a part of our news cycle. This doesn’t mean that by thinking about these existential or timeless questions around wisdom I am not aware of our world. I am. It is of course our world and the events within it that shape our daily lives. But I also believe that giving ourselves the time to think about our role in the world, our relationship with others, our own faith, and our identity beyond any given news cycle is a gift that I hope that everyone will take advantage of during these sacred days in order to be present for the year ahead.

“Let us not wait until someone dies to discover the true love in our relationship”

Rabbi Asher Lopatin, Jewish Community Relations Council/AJC, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

Sacrifice, but meaning, comes with a life of service and duty. That is one reason why we read the Binding of Isaac every morning — if we get to synagogue early enough — because it shows us the legacy that a life of sacrifice and service leads to.

So on the one hand, Queen Elizabeth II gave us a model for our own lives, and yet, she also in a strange way embodied a metaphor for our relationship with God:

The queen’s life was one of being a sovereign of the people (with even the prime minister bowing before her) but also a servant of the people. And that is what people really felt: that she ruled over them and served them as the ruler. My friend says that in business there is the concept of the “servant leader.” So it is fascinating that Hashem, too, is our sovereign whom we serve and worship and bow to, but also, in many ways, there is an element of God being in service of the Jewish people. After all, God sticks with us and compromises the model of perfection in order to be our leader. God forgives us, God gets angry with us, God commits to being with us through thick and thin. God our sovereign in a strange way is committed to serving the people He loves.

The relationship of the people to the queen, like the Jewish people to God, is one of both fear — awe — and, as we see at this time of her passing, great love. Ultimately, the Rambam and others say the ideal is a relationship of love and not fear. So let us not wait until someone dies to discover the true love in our relationship. And let us make sure that our relationship with God is filled with love.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.