Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Cornel West – two of the country’s most prominent academics and both African-Americans – have been speaking to a lot of Jewish audiences lately, decrying anti-Semitism in the black community.

Jews are pleased with these passionate pronouncements, but in the wake of recent incidents, they are beginning to wonder whom Gates and West truly represent – and who else is listening to them.

Gates, a professor of English and chairman of the Afro-American Studies Department at Harvard, called remarks about Jews by Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan “morally bankrupt” when he addressed several hundred people at a conference on anti-Semitism convened in Boston by the Anti-Defamation League earlier this month.

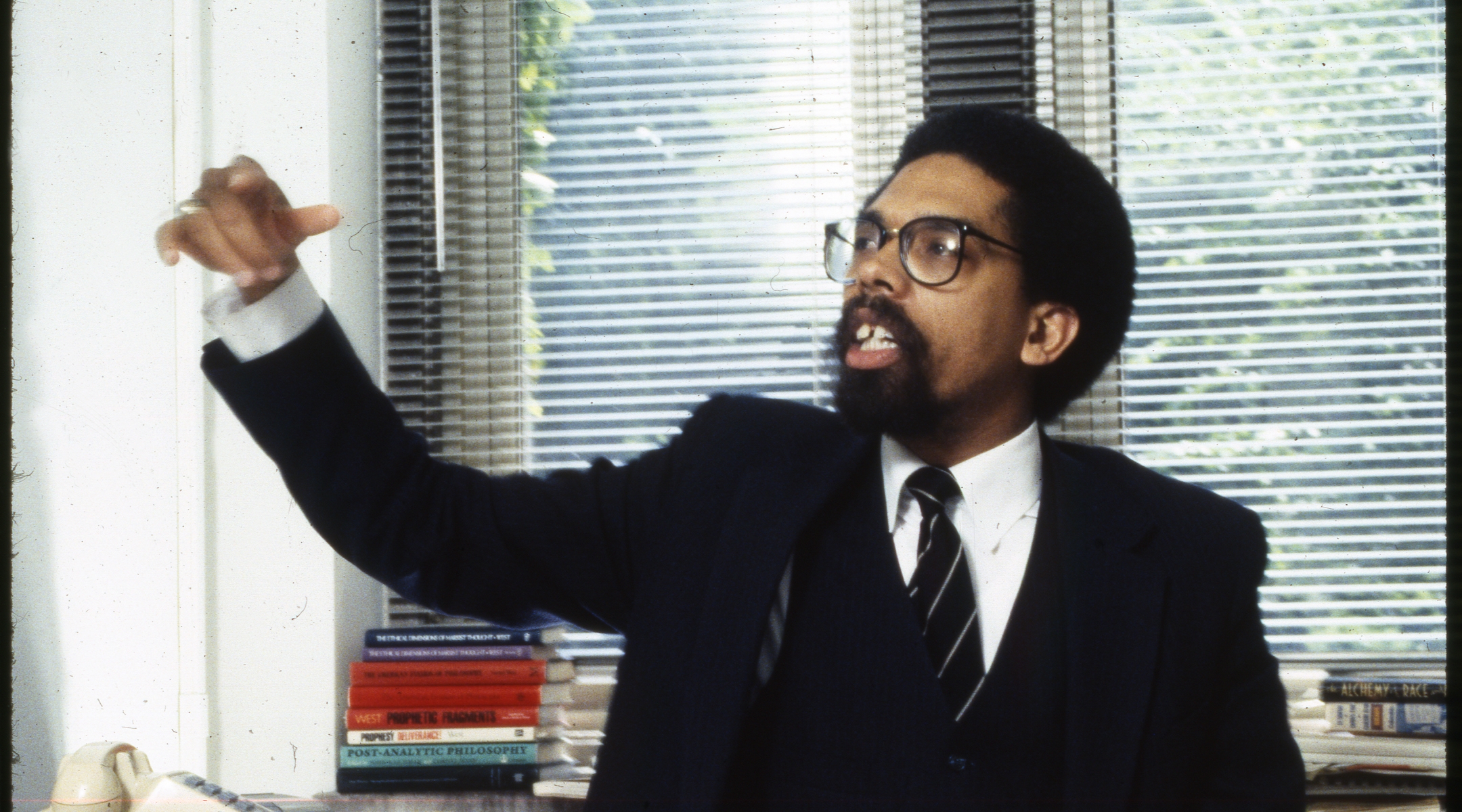

West, a professor of religion and director of the Afro-American Studies Department at Princeton, has addressed synagogue audiences and a hotel ballroom full of interested listeners at the Council of Jewish Federations General Assembly here on November 11.

Seen against the backdrop of recent survey data that shows that hard-core anti- Semitic attitudes are twice as likely to be found among blacks as among whites, Jews in just about every stratum of the community find deeply troubling the proliferation of black anti-Semitism.

The issue has been pushed into the spotlight by the death last year of a hasidic Jew at the hands of a black mob in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, the acquittal of the only man charged with his murder and the subsequent highly charged exchanges between black and Jewish leaders in the aftermath of the verdict.

The anti-Semitic propaganda campaign spearheaded by groups including the Nation of Islam and the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party is carried to every corner of the community by political leaders like the Rev. Al Sharpton, academics like City University of New York’s Leonard Jeffries, poets like Amiri Baraka and rappers like Public Enemy and Ice Cube.

According to their rhetoric and pseudo-scholarship, Jews were never really allied with blacks in the struggle for civil rights, but only wanted to control African-Americans; Jews are the controllers of power and money; Jews don’t want African-Americans to own their own businesses; and Jews were and continue to be the enslavers of blacks.

Even among many African-Americans who say they admire only the messages of black pride emphasized by these community leaders and reject the anti-Semitic component of the rhetoric, dangerous stereotypes of Jews are often unwittingly accepted along with the rest of the ideology.

These myths and their originators, say many Jews, are something too few African-Americans have been willing to repudiate.

To the Jewish establishment, Gates and West are two responsible voices willing to critique the growing popularity among African-Americans for scapegoating Jews for the social and economic ills that continue to beset the black community.

But there is some concern that these lone voices may not carry much weight in their own community.

What do blacks think of these internal critics? Are Jews holding dialogues with nationally prominent representatives of an otherwise silent majority or with pariahs largely marginalized by African-Americans?

When “Skip” Gates filled the entire op-ed page of the New York Times one day last July with well-aimed arrows of criticism of those blacks who spread anti- Semitic canards, he found himself roundly denounced by many blacks. His essay sparked a heated debate within the larger African-American community that has yet to subside.

Gates was not just criticized, but castigated, and received anonymous death threats for bringing into very public view an issue which many in the black community feel belongs behind their own closed doors.

Just after Gates’ essay was published, Minister Don Muhammed, head of the Nation of Islam in Boston, told a radio interviewer on WILD there that “Harvard has ruined more Negroes than bad whisky.”

Addressing Gates, he added, “Something is wrong with the black-Jewish relationship, Mr. Gates. Some of our people who call themselves educated are simply well trained.”

Questions about Gates’ motivation for focusing on anti-Semitism were widely discussed among blacks.

One African-American journalist suggested to a Jewish reporter that the reason Gates felt compelled to speak out on the issue was that Jewish foundations funded Gates’ graduate work – an assertion she had not attempted to verify before passing it along.

An impassioned exchange of correspondence debating the issue was published over several weeks in The City Sun, New York’s second largest black newspaper.

“When Gates wrote his piece people wondered what the politics were behind it,” acknowledged E. Ethelbert Miller, director of the African-American Resource Center at Howard University, a black university in Washington. “Some people are suspicious of him because he makes no bones about being a centrist. He’s no radical,” said Miller.

But that debate, in fact, may have sidelined the central issue that Gates tried to bring forward. West described the debate as one over “the politics of presentation” rather than anti-Semitism itself, and said that the shift may, in the end, quash the real dialogue that it should inspire.

“If we lose sight of the moral issue, it generates even deeper levels of distrust” between our two communities, West told Jewish federation leaders at the G.A.

But according to Gary Rubin, director of national affairs for the American Jewish Committee, Gates succeeded in his effort to place anti-Semitism on the agenda for discussion among black intellectuals.

“Coming out like that was a shock to the black community, but one which made them begin to take notice of something that they knew about but weren’t into discussing in a coherent way,” said Rubin. “If his aim was to get them to take this seriously, he certainly succeeded.

“The voices that have come out have been very critical, but have been very few and not very powerful,” said Rubin. “I take the large silence as a measure of quiet acquiescence.” He added that some African-Americans told him privately that Gates’ essay “was a breath of fresh air and needed to be said.”

According to some observers, West and Gates are not alone in their vocal opposition to black anti-Semitism.

Generally decrying anti-Semitism is not uncommon at meetings of black churches and organizations, West pointed out.

Even Rev. Jesse Jackson, long the hope of many African-Americans for national office, but whose infamous “Hymietown” comment during the 1984 presidential campaign became a thorn in the side of organized Jewry, condemned hatred of Jews in two headlining speeches last July, at the Democratic National Convention and to a World Jewish Congress meeting in Brussels.

“The Jewish community has been fixated on the voices of anti-Semitism, and not hearing the voices of conciliation and outreach,” said Rubin.

Black ministers have been among the most vocal opponents of anti-Semitism among African-Americans and have reached huge numbers of black Americans in their churches, according to West. “These pastors are well respected around the country and preach in a variety of different pulpits throughout the year, and are not as insulated as one would think,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

And according to Jackson, the health of the black-Jewish coalition should be measured by the “good working relationship” of black and Jewish members of Congress, and of black mayors and the Jewish communities in their cities.

“In my travelling, the black-affirmed relationship is more the rule than the exception,” Jackson told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

But West acknowledged that no matter how popular the preacher, a message from the pulpit does not have the same impact on the community as one from a political leader. “When you have access to radio and television, you have much more access to the community,” he said.

And as influential as they may be in the world of academia, the credibility of Gates and West among African-Americans may not extend far beyond the gates of their Ivy League campuses, said Miller of Howard University.

“As intellectuals, Gates and West can take a more principled position than a politician can. It’s not as if you’re dealing with people who represent organizations. They’re individuals,” he said.

Given the statements of Gates and West, and the furor that followed Gates’ op- ed, what do their efforts signify about the future of black-Jewish relations?

According to some observers, the fact that two individuals as prominent and respected in intellectual circles as Gates and West have so clearly repudiated anti-Semitism in their own community can only promise more of the same.

“This powerful pull to the center is of enormous significance to legitimize other black figures who want to confront this extremism,” according to Rabbi David Saperstein, director of the Reform movement’s Religious Action Center and a longtime civil-rights activist. Saperstein described Gates’ and West’s willingness to speak out against anti-Semites in their own community as indicative of “a sea change” in the black community’s attitudes, adding that “it can only be healthy.”

AJCommittee’s Rubin said Gates’ and West’s statements gave “new prominence and visibility to this voice,” but he warned that “it will have no importance at all if it’s considered just the courageous voice of one or two people unconnected to the larger community.”

Reconstituting the black-Jewish alliance will depend on “putting out human hypocrisy wherever it is found, in the black community and in the Jewish community,” said West. “One must stand up with moral courage and not lose sight of the substance and still keep our eyes on the prize, which is to eradicate all kinds of xenophobia.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.