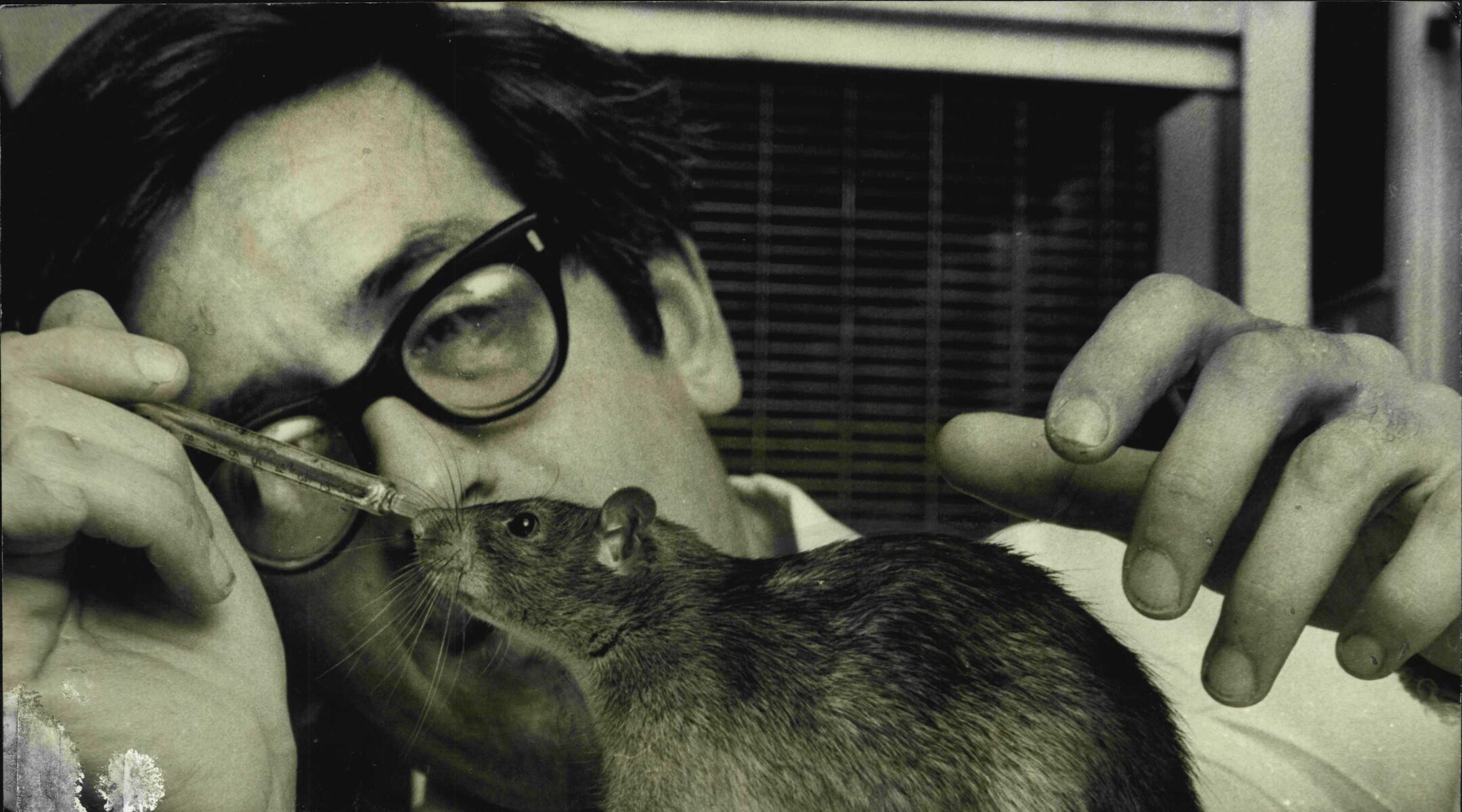

In the early 1960s, just before Flower Children started smoking pot, a young organic chemist with a fondness for medicinal plants isolated the first known cannabinoid, THC, from an 11-pound lump of hashish appropriated by Jerusalem police. Mechoulam, now 70, went on to discover more than just the first active compound found in marijuana and hashish. In fact, the past 40 years of his career have laid the groundwork for how researchers work with a group of chemicals called cannabinoids, some of which occur naturally in the human body.

Affecting different parts of the organism, cannabinoids can be applied in areas such as pain relief, cancer treatment and diet suppression.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June that terminally ill patients with doctors’ prescriptions for marijuana will be prosecuted for violating federal drug laws — even if their home states allow marijuana use for medical purposes — a late June meeting of the International Cannabinoid Research Society in Tampa, Fla., showed how important cannabinoids are becoming for commercial drug research.

Hobnobbing with the research scientists were executives from drug giants Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Merck, Glaxo Smith Kline, Bristol-Meyers Squibb and Sanofi-Aventis, who came to explore the society’s latest research.

When the society first convened in 1991, it consisted of a small clique of esoteric scientists who shared novel research. Almost 15 years later, the group is grabbing the attention of billion-dollar drug developers and is sponsored by the National Institute of Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Health Canada.

Richard Musty, the society’s director and a psychology professor at the University of Vermont, told JTA that large pharmaceutical companies are eager to find a way to cash in on cannabinoid research. As early as next year, he noted, Sanofi-Aventis hopes to have the first synthetic cannabinoid drug on U.S. shelves. The pill currently is in advanced stages of clinical trials.

Drug developers at Sanofi-Aventis have studied and tweaked the chemical “handshake” that occurs between brain neurons and cannabinoids in the brain’s reward centers. Through a process that essentially reverses the handshake, the company hopes to inhibit food intake in overweight people who may be at risk of cardiovascular disease — potentially giving Sanofi-Aventis a large chunk of a diet-pill market that Musty projects will reach $5 billion.

At the society meeting, Mechoulam handed the R. Mechoulam Annual Award to George Kunos from the National Institutes of Health for work in cannabinoid research. Ironically, the NIH was one of the first bodies to deny Mechoulam research money for isolating cannabinoids in the 1960s.

“Israeli scientists have a way of entering areas where others fear to tread,” explained Bernard Dichek, publisher of the biotech monthly BioIsrael. “When Mechoulam’s American contemporaries were either smoking marijuana or condemning those who did, Mechoulam forged ahead with the science and discovered the active ingredient anyway.”

Mechoulam’s seminal work has made the Hebrew University of Jerusalem an international research hub on cannabinoids, with drug developers and health professionals often coming to consult with Mechoulam. Mechoulam leads a team of doctoral students at his Jerusalem laboratories, and his patents are being commercialized by Pharmos, a NASDAQ-traded company with offices in Iselin, N.J. and Rehovot, Israel.

A new drug from Pharmos, Cannabinor, is to begin clinical trials soon in Munich. Cannabinor could fill a hole in the pain-relief market as doctors become reticent to prescribe Vioxx and other widely used pain drugs because of safety and other concerns.

Pharmos ultimately aims to use Cannabinor to treat moderate to severe post-surgery pain and alleviate lower back pain and pain associated with cancer. Today, patients rely mostly on opiates to gain even moderate relief, but opioid compounds have substantial unwanted side effects such as addiction and constipation.

Like the Sanofi-Aventis diet-pill formulation, Cannabinor is a synthetic compound that provides therapeutic benefits without the psychotropic effects associated with marijuana and hashish. Pharmos began collaborating with Mechoulam more than 10 years ago and has a large lead on any other cannabinoid pain-drug contender.

Some companies — such as the United Kingdom’s GW Pharmaceuticals, which makes Sativex, now available in Canada — provide a natural cannabinoid plant extract for various therapeutic uses. But the synthetic compounds developed by companies such as Sanofi-Aventis and Pharmos are far more potent than plant formulations that have been used medicinally for millennia.

Reports indicate that as early as 2737 B.C.E., the emperor Shen Neng of China was prescribing marijuana tea to treat gout, rheumatism, malaria and poor memory. The drug’s popularity as a medicine spread throughout Asia, Africa and later the Middle East.

Hashish has been smoked in the Middle East for centuries, Mechoulam notes, and the use of marijuana and hashish is very common among today’s Israeli youth. But the synthetic products are much more effective as medicine, Mechoulam says.

“The problem of medical marijuana and hashish in its pure form is that although it is a good drug in certain diseases, it cannot be used clinically because a patient may get a different concoction every time one inhales,” he says.

Mechoulam rarely uses the raw material in his research today. He prefers to study endocannabinoids, which are cannabinoids that occur naturally in the bodies of humans and animals.

His most recent source of pride is doctoral student, Natalya Kogan, 25, who has developed a cannabinoid derivative that shows promise in fighting cancer by befuddling cancer cells’ genetic material, leading to cell starvation.

Kogan, who works under Mechoulam at Hebrew U.’s School of Pharmacy, received a Kaye Innovation Award in June, an annual award for innovative research in Israel. Ironically, her prize was given within a week of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing medical marijuana.

The ruling did little to deter the researchers who met in Tampa. Musty, the professor from Vermont, says the society takes no official stance on medical marijuana.

“Any scientist that belongs to our society can voice a personal opinion,” he says, “but in the medical applications of cannabis, most people would support that a non-smoked format would be the best way to go.”

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, JTA can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.

The Archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency includes articles published from 1923 to 2008. Archive stories reflect the journalistic standards and practices of the time they were published.