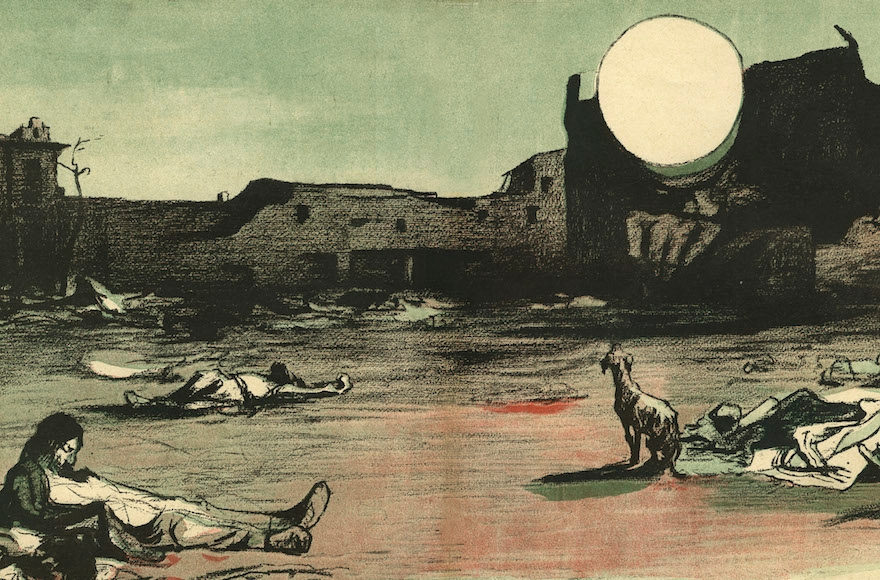

SAN FRANCISCO (J. The Jewish News of Northern California via JTA) — There was a time when “Kishinev” was all you had to say. The three days of brutal anti-Jewish violence in 1903 in the capital city of present-day Moldova introduced the world to a new word — pogrom — and for years afterward colored the way Jews and others viewed Jewish life in the Russian empire.

Soon other names took its place in the lexicon of anti-Jewish horrors — Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Babi Yar. But Kishinev, even with its “mere” 49 dead, echoed as a foreshadowing of the century’s horrors.

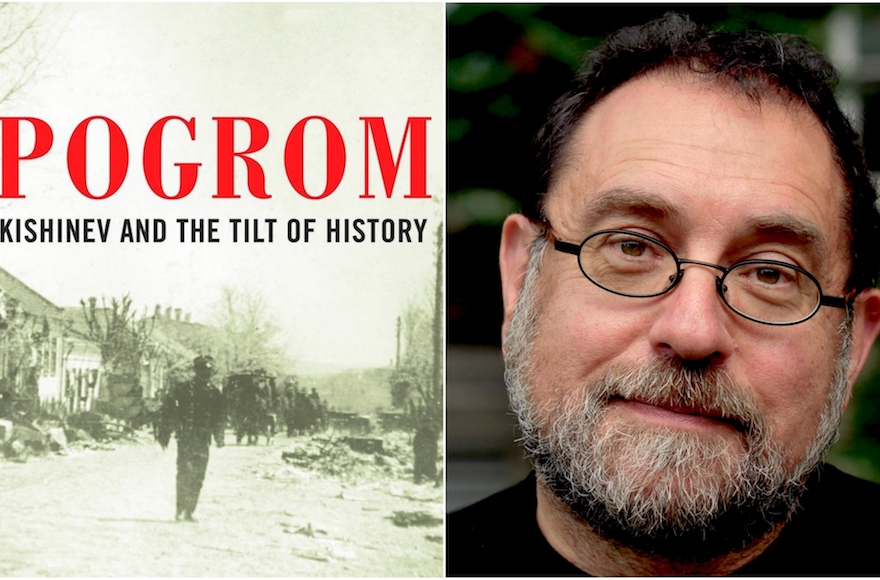

Steven Zipperstein’s new book, “Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History” (Liveright/W. W. Norton & Co.), does much more than retell a story worth remembering, although it does that in compelling, heartrending detail.

Through dedicated research in several countries and as many languages, including a fortuitous gift of astonishing handwritten documents from the most notorious anti-Semite in late tsarist-era Kishinev, the Stanford University historian has shown us an early example of the power of the press, brought to light the story of a San Francisco Jewish woman instrumental in forming the NAACP, built an ironclad case for the true authorship of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” and explained how the fallout from this tragic tale gave rise to the myth of the weak Diaspora Jew that persists to this day.

And he reveals how much of what we think we know about the pogrom itself is wrong.

Zipperstein didn’t set out to write this book. He had planned for a larger work on 200 to 300 years of Eastern European and Russian Jewish history. But the Kishinev pogrom, carried out by a mob beginning on Easter Sunday, April 6, 1903, caught his attention early on.

“This event helped shape so much Jewish self-perception this past century,” he told J. “But it did so much more than that.” And much of its lingering impact is due to misunderstandings — and also a cluster of forgeries — that have shaped the memory of Russian Jewry’s best-known disaster ever since.

“Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History” is a new book by Steven Zipperstein. (Liveright Publishing/Tony Rinaldo)

“We learn so much about Russian Jewry from press coverage of Kishinev, and so much gets skewed,” he said.

Myth No. 1: The Jewish men of Kishinev hid in fear while their wives and daughters were raped and killed. That’s the story told in Israeli textbooks of the 1950s, one cemented in the worldview of the prestate Haganah, itself colored by Hayim Bialik’s remarkable poem “In the City of Slaughter.” The highly influential work told of “husbands, bridegrooms, brothers” who crouched “in that dark corner and behind that cask” watching as their “virginal daughters … were fouled.”

In fact, as Zipperstein came to understand it based on his archival work, Bialik’s poem erased much of the truth: that there were Jewish men who fought back against the marauders who attacked and wounded more than 600 of their people and destroyed more than 1,000 of their homes and businesses. Most were themselves wounded or killed.

Myth No. 2: The Kishinev pogrom was sanctioned, if not instigated, by the tsarist government, with the complicity of the local police.

Not so, says Zipperstein. The ground was laid and the hatred fanned by a local anti-Semitic newspaper run by a notorious Jew hater named Pavel Krushevan, himself the most likely author of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion.”

“I discovered that the word ‘pogrom’ was only sketchily used before mid- to late 1903,” he said. “It was part and parcel of a larger arsenal of words used for riots in Russia, not necessarily against Jews.”

That changed after news of the Kishinev violence spread.

“While the term well into 1903 is italicized by the European press, by 1904-05 it is a term as widely recognized as the words vodka or tsar,” Zipperstein said. “In the West it comes to mean a government-condoned or organized attack on Jews. That’s all the more intriguing because the event that led to this understanding, Kishinev, was not organized by the government.”

Two powerful portraits of little-known actors emerge from the pages of “Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History,” each worthy of a separate book.

First is Krushevan, to whom Zipperstein devotes an entire chapter.

Just about a month before completing his manuscript, Zipperstein came across an amazing collection of the man’s handwritten documents that had been carried to the United States in the 1990s by a Moldovan Jewish immigrant, who obtained them from a mental hospital where Krushevan’s nephew was incarcerated. This invaluable primary source material bolsters the notion that it was Krushevan himself who wrote the infamous “Protocols.”

Appearing just months after the massacre, the fake manuscript suggests that the extensive press coverage of this “tiny” incident in a neglected corner of the empire is further evidence of the global power wielded by world Jewry.

Zipperstein says this same pogrom gave rise to the enduring twin canards of the powerless Jew and the all-powerful Jew.

Another portrait features Anna Strunsky, a Jewish journalist from San Francisco and a graduate of Stanford University who married a fellow Jewish writer with similar radical sympathies. It was in her New York apartment where the founding meeting of the NAACP was held n 1909.

This linking of the black and Jewish causes, which led to a decades-long alliance culminating in the civil rights struggle of the 1960s, was — if one can say such a thing — a happy outgrowth of the Kishinev pogrom. As news of the tragedy flooded the New York press, it energized the leftist Jews of the Lower East Side. Eager to universalize their championing of the underdog, they began to draw comparisons between Jewish oppression in Russia and black oppression in the United States. Anti-black lynchings had their parallel in anti-Jewish pogroms, and both were deserving of (progressive) Jewish attention.

Above all, Zipperstein’s book is about the power of the media, politics and folklore to shape history and memory.

As he writes in conclusion: “The interplay between the wealth of readily accessible information regarding Kishinev’s massacre – a veritable mountain of data – and the proliferation of distortions regarding it remains perhaps the saga’s most profoundly intriguing legacy.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.