(JTA) — I first saw Catie Lazarus do stand-up in 1996 in a wadi in the Judean desert. She was 19, I was 21 and we had both signed up to be “chevre” (literally, friends) on an Israel immersion program called Livnot U’Lehibanot, To Build and To Be Built. A bit clueless about what we had gotten ourselves into, we spent our days hauling bricks to and from construction sites around Jerusalem, attending classes about the rules of modesty as it pertains to Jewish women, hiking the beautiful, hopeful country that existed in the mid-’90s, crossing deserts, mountains and bridges, singing niggunim on rooftops. She mostly got in trouble for questioning everything we were learning.

Lazarus, a comedian, writer and producer, died Dec. 13 at 44 of terminal cancer. She was known for the intellect and heart that she brought to her comedy, and her brilliance, wit and endless capacity to love is both celebrated and mourned this week. The recurring live show she created, “Employee of the Month,” brought A-list stars on stage in New York City to talk about what they did everyday for work as a way of life, and she was celebrated in the writing and arts communities for her warmth and ability to bring a room full of strangers together. She was also a noted interviewer and writer outside of her lauded show and published a series in The Atlantic on life after losing a job.

But long before her own celebrity, and throughout her success, she was my friend.

I had left America that summer because I was running away. My mother had just died of breast cancer at the age of 48. Unmoored from her death and newly graduated with a degree in English literature, I went to Israel. Catie was the first person I met at Livnot. Our hikes were the perfect space to share, to be heard. I told Catie that I was a dancer, like my mother who had gone to Juilliard. Catie’s whole body lit up, and she glowed talking about the transformative power of dance, how it connected people to one another. She spoke of how moving in a space could make a person transcend time. It was a moment of perfect understanding and I loved her for it. She was fully present for me and for my pain. We soon became inseparable, and I’d often be the go-between between her and our program leaders with whom she often clashed. Acceptance without questioning was never her thing.

Catie was, even then, absolutely hilarious. The desert comedy performance was part of a talent show put on during an overnight camping trip. Under the vast expanse of the starry desert night sky, with an audience in sleeping bags, most showcased their fledgling guitar skills (think off-key renditions of “Wonderwall”). Then Catie was up. She was bitingly self-deprecating, telling a story of how she joined a gym in the city only to retreat to the locker rooms because of all the fashionable blonde gazelles that bore no semblance to her Semitic (i.e., short and dark) genes. She held us with this juxtaposition — how could someone so acutely aware of their perceived shortcomings absolutely transfix us and command the room?

That fall I moved to Washington, D.C. Catie was raised in northwest D.C., which was often the butt of her jokes about privileged access to power, wealth and ill-fitting khakis. She descended from an influential Jewish family, which started one of the country’s first department store chains. Her father advised President Jimmy Carter.

Catie started a doctorate in psychology and learned how to listen professionally. I learned how to be on my own. Motherless and pre-internet, I felt alone and ungrounded.

Catie would rescue me, tuck me into her childhood spaces, the ones she had escaped, the ones she returned to. “Come to my parents’ house,” she said, when I was alone and sick with the flu. “Tina will take care of you.” Tina lived with the Lazarus family and took care of their house and the Lazarus kids. Catie loved Tina fiercely, like another mother. I slept in Catie’s room while Tina fed us soup.

Before too long, Catie had left the psychology professional track and moved to New York to pursue comedy, which was a faster, truer path to the stories she found so fascinating. In 2010, she launched “Employee of the Month,” which would become a regular fixture at Joe’s Pub in downtown Manhattan. Catie being Catie was the draw, as much as the myriad of celebrities who ended up sharing her stage. Her capacity to observe and open up subtleties of behavior was exquisite. She had the unique ability to expose the absurdity of an institution, idea or group without malice or bitterness.

Despite her D.C. upbringing, Catie’s was a New Yorky, Jewy feminist comedy, but a brand all her own, sharply honed by the things she found hard in life and what she loved best — observing people and getting everyone, from stars of the brightest wattage to your average person on the street, to reveal his or herself in unexpected ways.

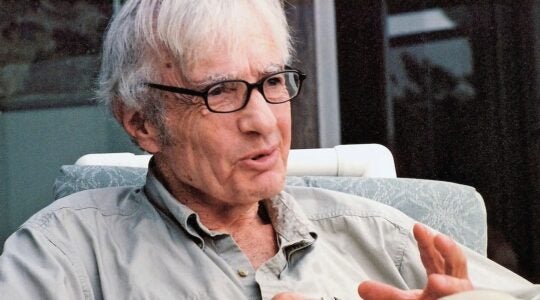

The author Maia Magder, left, with Catie Lazarus and her dog, Lady. (Courtesy of Magder)

Sometimes the show went on the road, and Catie performed at the Kennedy Center and at nightclubs in D.C.. Her show would often start with a monologue, dance or even a puppet show. It was always joyful, zany and full of life. When the show came to D.C., her family was almost always present in some combination of Lazari. In the early to late 2000s, her brothers, Ned and Ben, and sister-in-laws, Nahanni and Katherine, along with Catie’s parents, would attend. That wasn’t always comfortable.

“It’s a little hard to tell a blow-job joke when your dad is sitting in the fourth row,” she said once, deadpan. Catie would also tease the D.C. audience for being so hopelessly “Washington,” and it was apparent that hers was a soul that belonged to New York.

As public as her professional life became, Catie was a fiercely private person. Though universally celebrated for her authenticity and tremendous talent, she was critical of herself, and it came out in all areas of her life. Despite her success professionally — so crystal clear to those around her — she did not feel she had “made it” or reached a pinnacle, and there were works she still longed to create. The constancy of creation propelled and haunted her. As such, she left things unfinished not only in work, but also in some relationships in her life.

When Catie was first diagnosed with cancer in 2014, I was incredulous. I had made the decision just the year before to have a prophylactic double mastectomy, so the contrast in our paths was suddenly stark. Catie advocated for herself at the hospitals where she was treated, and she still showed up relentlessly for her shows, her writing, her projects and for her friends. She never wanted cancer to define her, and she never diminished any problem I was having by comparing her life to mine. She was undergoing treatment the week I came to watch her grab one of the year’s most coveted interviews for “Employee of the Month”: Jon Stewart, the week he left “The Daily Show.”

Catie continued to write, book and produce “Employee of the Month,” all while in various phases of treatment. Her show was who she was — someone who gave people platforms to tell their own stories in ways that allowed the audience to find themselves in their narrative. Her guests’ industries were wildly different: NGOs (documentary filmmaker Julia Bacha), news (Leslie Stahl of CBS), political and social justice (Gloria Steinem), art and music (Lin-Manuel Miranda), even puppet comedy (Triumph the Insult Comic Dog). But the intimate connection to her guests was the connecting thread.

Yet Catie, in all her connectedness, was decidedly independent. She moved through her different worlds of family, friends and industry with thought, determination and — I’ll say it — control. She was known to want to do everything for herself. I loved her for this, and I gave this to her in our friendship. But it also speaks to why so many people who loved her fiercely reacted with such surprise to know she had left us all, bereft and too soon.

I came to Brooklyn last Thursday to be with Catie before she died. She had been extraordinarily clear in how she envisioned her death: She wanted to be home. I came and sat with her and Nahanni by her bedside after we drove all day to reach her.

“Oh, Maia,” she said, turning to me, still witty, still Catie. “What a surprise! You came to Brooklyn!” Her dog, Lady, snuggled closely at her side, and I sat at her bedside — masked, ungrounded once more.

As she prepared to cross this final bridge, this time alone, we held hands and were able to connect one last time.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.