(JTA) — In her new book “Bad Jews,” Emily Tamkin frames recent American Jewish communal politics as a series of clashes between antagonists who insist there are right ways and wrong ways to be Jewish — that is, “good Jews” and “bad Jews.” It’s a useful and revealing way to look at how Jews fight among themselves.

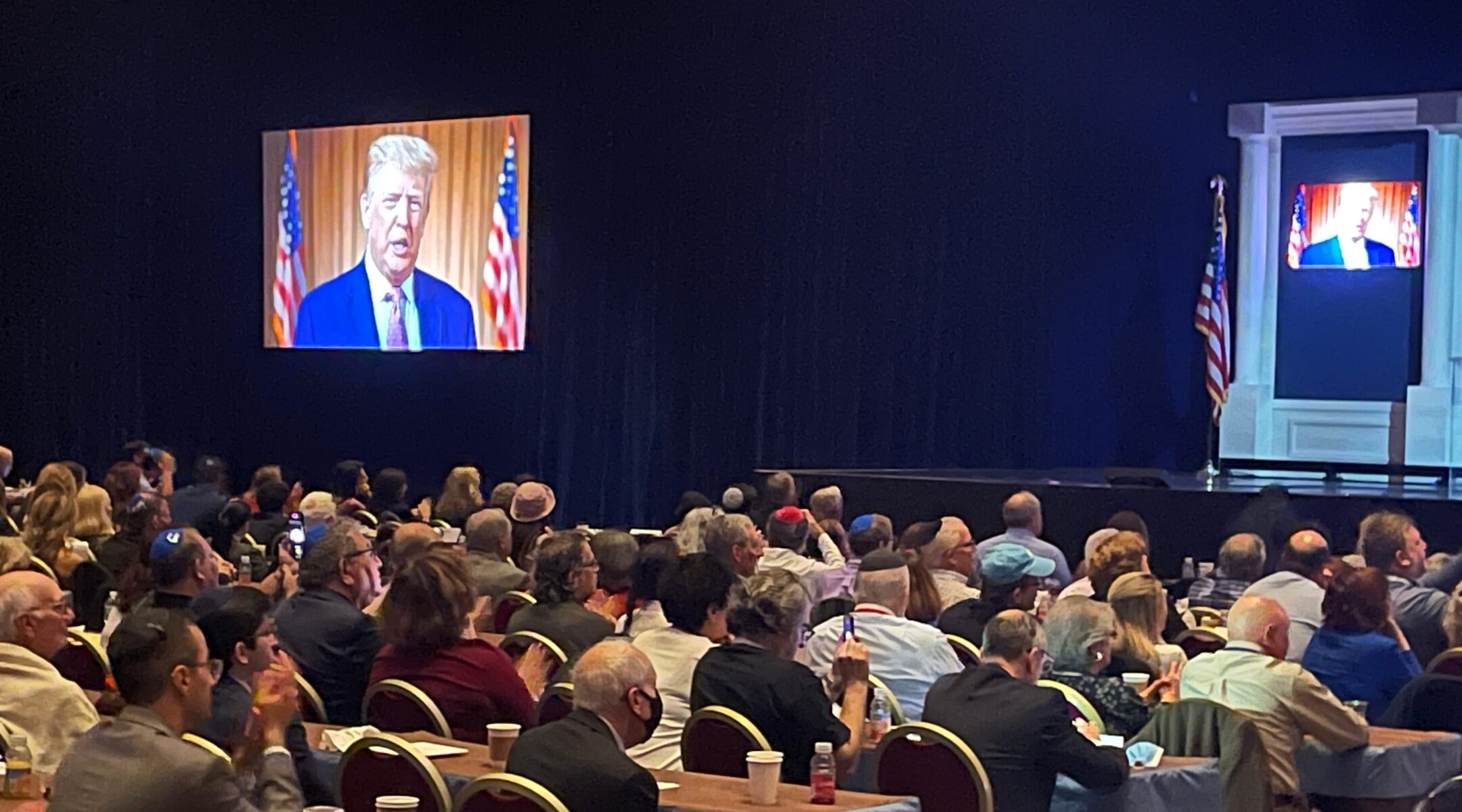

It’s also incredibly timely (or timeless). Donald Trump had his own version of “bad Jews” in mind when he tweeted this month that American Jews were insufficiently grateful to him for his support of Israel, and warned that “U.S. Jews have to get their act together and appreciate what they have in Israel — before it is too late!”

Some Jewish groups heard that as an antisemitic threat. Even giving him the benefit of the doubt — I thought he meant that Israel itself would be in danger if Jews didn’t vote for a pro-Israel president like him the next time — it does fit into a pattern in which Trump treats “the Jews” as a monolith, and distinguishes between the good Jews who vote for him and the bad Jews who don’t recognize their own self-interest. That sort of ethnic pigeonholing never ends well. And as I have written before, I don’t know if Trump is antisemitic, but he has certainly been good for antisemitism.

Trump was also echoing the kinds of internal Jewish conversations that Tamkin describes. It may be presumptuous for a gentile politician to explain how “good Jews” vote, but Jewish individuals and organizations have been doing it for years. Liberal Jews use the “good Jew/bad Jew” framing, on everything from immigration to LGBTQ rights. But it has over the years become a conservative specialty, especially when it comes to Israel:

- In 2002, New York Times columnist William Safire urged Jewish Democrats to put their domestic agenda aside to vote for Republicans he felt had a better record on Israel.

- In 2008, neoconservative icon Norman Podhoretz lamented that liberalism had “superseded Judaism and become a religion in its own right.”

- In 2011, Jewish conservative firebrand Ben Shapiro tweeted, “The Jewish people has always been plagued by Bad Jews, who undermine it from within. In America, those Bad Jews largely vote Democrat.”

- In 2018, Jonathan Neumann turned that idea into a book-length attack on Jews involved in social justice movements, subtitled, “How the Jewish Left Corrupts and Endangers Israel.”

In each case, the writers implied that good Jews put the fate of Israel ahead of other values — which, to the degree that they are liberal, seem to the writers barely Jewish in the first place.

Some of those objecting to Trump’s tweet said it fed the “dual loyalty” accusation — that is, Jews pledge their true allegiance to Israel. But again, Trump is turning an internal Jewish discourse back on itself. Let’s be honest: Caring about the well-being of Israel — political, social, military — is a normative value in the vast majority of American Jewish settings: synagogues, schools, summer camps, community councils. That’s not dual loyalty, but solidarity with millions of co-religionists and extended family members. Such solidarity is the right of any ethnic group, and Jews have rightly owned it, even as polls show that is the minority of Jews who make Israel their number one issue at the polls. Trump’s tweet is a funhouse version of that tendency — demanding Jews stand in solidarity with Israel but on his terms, and exclusive of other priorities.

Trump’s tweet is of a piece with what Maggie Haberman, in her new book about Trump, describes as the “racial tribalism” the real estate mogul absorbed in the New York City of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. In that Archie Bunkerish New York, individuals were pegged and defined, for good and ill, by their ethnicity. In Trump’s view, Jews are good business people, savvy negotiators and of one mind when it comes to Israel — and are confounding and even ungrateful when they are not. That’s the Trump heard in a recent video clip, asking if the filmmaker was “a good Jewish character.” Good Jew or bad Jew?

Tamkin calls her book an attempt to “wrestle with what I believe to be the one truth of American Jewish identity: it can never be pinned down.” Still, a lot of people have tried — sometimes out of the best of intentions, and sometimes to push people out of the fold. When we presume to tell ourselves who is and isn’t a “good Jew,” however, we shouldn’t be shocked when others — especially a politician who has made racial tribalism his brand — do the same.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.