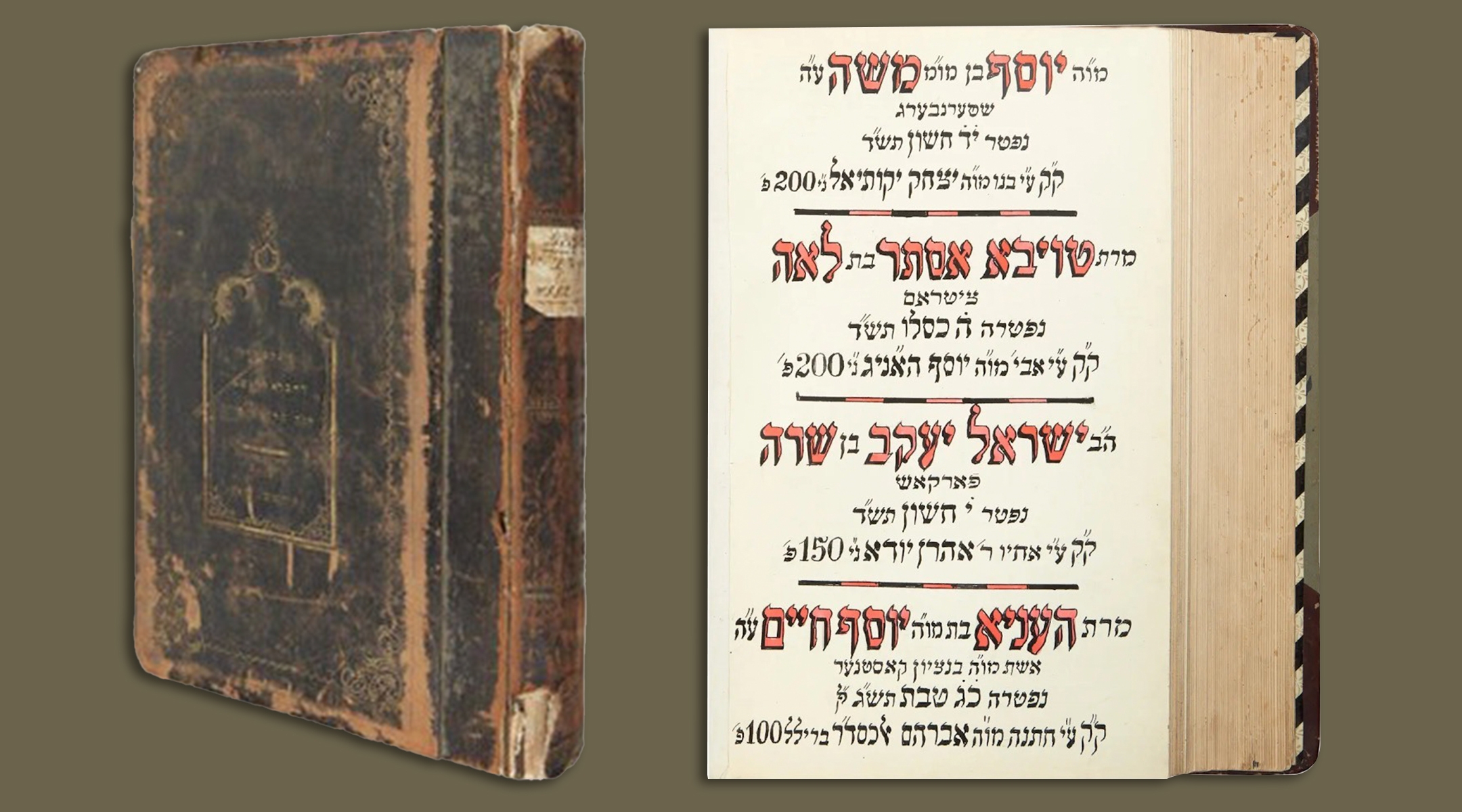

(JTA) — In 2021, a leather-bound book dating from the second part of the 19th century came up for sale at a New York auction house, together with other similar works. Originally from the Jewish community in Oradea in today’s Romania, the ledger listed Jewish burials in the city between 1836 and 1899. A page on display listed, in elegant Hebrew calligraphy, the names of those who passed away.

One of them is identified simply as Tova Esther, the “daughter of Leah,” who died on the fifth day of the month of Kislev in the Hebrew calendar. How did this precious book reach New York in 2021? Alarmed that a pre-war treasure of Romanian Jewry may have been looted by the Nazis and passed through private hands before coming up for auction, the World Jewish Restitution Organization — which I lead — together with the Romanian Jewish community approached U.S. authorities to ensure that the auction house call off the sale until its provenance could be determined.

What other paintings, books and kiddush cups that tell the story of a family and represent the history of a people lie today behind closed doors and in private homes?

Twenty-five years ago, in a very different world, over 40 countries adopted the Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. They laid out first steps to create an international understanding on how to best deal with the problem of Nazi-looted art. It was the beginning of a journey that has affected the way that we look at issues of ownership, history and transparency in the world of art and cultural property. But the journey is not yet completed.

A gathering in Washington last week took stock of progress and at the same time charted new directions forward. Under the leadership of the United States, 23 countries came together to endorse a set of best practices and to invite other countries to endorse them. Notably, the gathering included a focus on looted Holocaust-era art and cultural property that is today in the hands of private individuals.

We have seen great progress over the past 25 years, but there is clearly much to do. As a global report released last week shows, while claims processes are now in place in many countries, the numbers of cases handled and resulting restitutions often remain low. Five of the 47 countries surveyed in the report have established restitution commissions to facilitate claims, but the overwhelming majority of countries still do not have one. Overall, 24 countries have made little or no progress in implementing the Washington Conference Principles.

The new best practices adopted this month call on governments to encourage projects that will make available on the internet not only public but also private archives. “Public and private collections should be encouraged to publish their inventories,” the governments urge. The records of dealers and others that facilitate the art market can hold the key to unlocking the past. Privacy is a value we all share, but so too is the quest for justice.

Two portraits by Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele seized from American museums in September 2023 were restituted to the heirs of Viennese Jewish cabaret performer Fritz Grünbaum. (Chris Delmas for AFP via Getty Images)

Our attention tends to be drawn to high profile cases of looted paintings by luminaries like Pablo Picasso and Egon Schiele hanging in storied museums across the world.

But this is also a story of drawings, of silver kiddush cups and musical instruments and libraries. It is about items that are often of limited financial value but of immeasurable historical significance to families and to the Jewish people. For every renowned masterpiece that was taken during the Holocaust, there are hundreds of lesser-known works and religious artifacts. They came from great cities, from small towns, and from tiny villages. Some were created by people whose famous names roll off our tongues, and others by anonymous craft workers toiling in obscurity in their studios.

Why do they matter? Because they bring us closer to lives that were destroyed and to memories that were lost. They represent the heart of a family, the heritage of a community, the soul of a people. They tell us where we came from and who we are.

And, as we are increasingly discovering, artwork and artifacts that belonged to families and to Jewish communities before the Holocaust are not just in the great museums around the world; many also ended up in private homes.

Lack of transparency, long a hallmark of the international art trade, stymies the efforts of those that are seeking the return of the art and cultural property that belonged to families and Jewish communities. The search for history often runs into the roadblock of privacy and secrecy. And that is frequently where the trail runs cold.

The memory of Tova Esther belongs to her family, and to the Jewish people — not to a private individual. We must seek not only the restitution of property but also the restitution of history.

At a time when we as a society are increasingly examining the origins of items of art and culture, this is a moment that calls for us to shed light on the darker chapters of history and to promote openness amidst opacity.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.