Ahead of Israeli super welterweight champion Yuri Foreman’s highly anticipated Yankee Stadium fight in 2010 against Miguel Cotto, a press release hit journalists’ inboxes touting Foreman’s “shofar-driven ring entrance.” Another quote welcomed fans to “Yankel Stadium.”

The taglines spoke to Foreman’s unusual biography: An Orthodox Jew born in what is now Belarus, he had spent much of his childhood in Israel before moving to New York. He was also studying to become a rabbi.

They also opened a window into the mind of the man who wrote the press release: Fred Sternburg, a veteran promoter with a passion for both boxing and Judaism.

His efforts didn’t end with the PR pitch: Sternburg and his mentor Bob Arum, who is also Jewish, arranged for a shofar to be blown at the Saturday night fight, dubbed the “Stadium Slugfest,” which began only after Shabbat ended. It also featured a performance of Israel’s national anthem. Sternburg said his whole family was rooting for Foreman, who lost the fight by technical knockout in the ninth round.

“Working with him was an absolute pleasure because I think he was the first Orthodox Jew to win a world championship in boxing,” Sternburg told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “It was just a great story. How do you forget something like that?”

After nearly 40 years of pitching clever boxing storylines, Sternburg, 65, is taking center stage for the first time: On Sunday, June 9, he will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York.

“No one’s more shocked than I am that this is even happening, because most Halls of Fame should be focused on the athletes, which they are,” Sternburg said. “But then they create other categories for supporting acts and I guess I’m one of them.”

Sternburg has also pitched articles about journalists, authors and documentarians (including to this reporter) but boxing is in his blood: His father boxed at Georgetown University in the late 1940s.

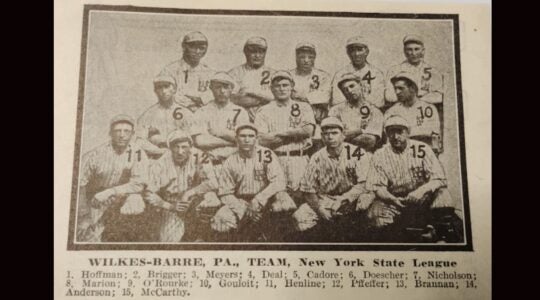

Sternburg also said it means a great deal to him to be part of the long, largely bygone legacy of Jewish boxing excellence in the United States. In the 1920s and 30s, Jewish world champions like Barney Ross and Benny Leonard were among the biggest names in the sport. Now Sternburg’s name will be alongside theirs in the Hall of Fame.

“There is that lineage,” Sternburg said. “Not that I’ve ever taken a punch, but it’s kind of nice to be associated with it.”

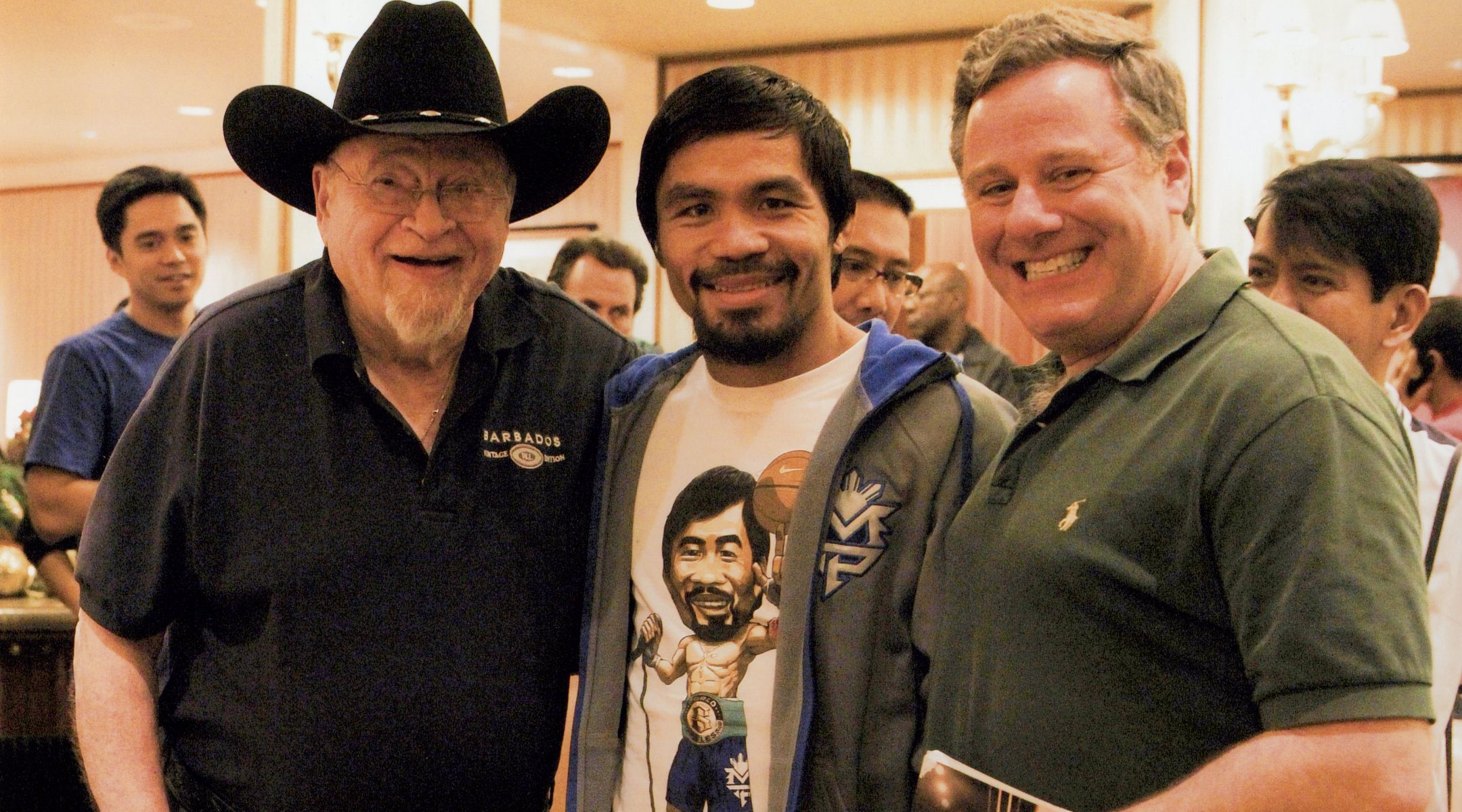

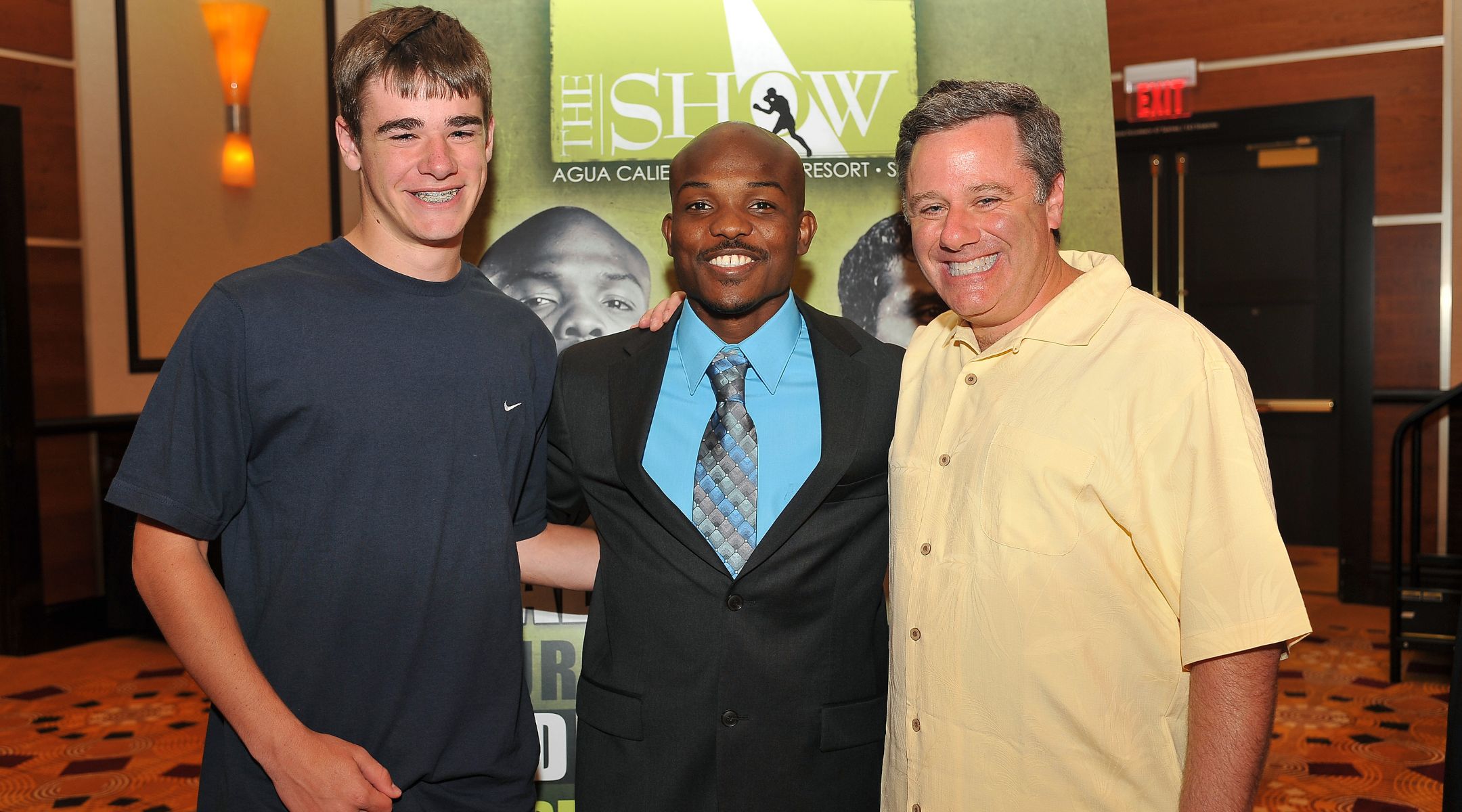

Fred Sternburg, right, with his son David, left, and two-division world champion Timothy Bradley. (Courtesy of Fred Sternburg)

A Washington, D.C. native, Sternburg tried law school and real estate before discovering his true passion. A colleague’s husband introduced Sternburg to Charlie Brotman, a Jewish public relations maven who ran one of the premier sports and entertainment agencies and who represented boxing star Sugar Ray Leonard.

Sternburg interned at Brotman’s namesake firm, helping promote tennis and golf tournaments, when he got his first taste of big-time boxing PR: Sternburg and Brotman promoted Leonard’s famous 1987 bout with “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler.

At the November 1986 press conference announcing the fight, Sternburg arranged for local and national news outlets to interview the two fighters, which generated a great deal of attention for what would be billed as “The Super Fight.”

“I’m having the time of my life at this thing, thinking, well, if this is boxing, count me in!” Sternburg recalled.

The opportunities began to pile up: Sternburg worked as a publicist in the D.C. area, promoting mostly local fights with lesser-known boxers. As his profile, and those of his clients, began to grow, Sternburg took on bigger and bigger names and fights, eventually joining the America Presents promotion company in Denver. He created his own firm, Sternburg Communications, in 2002.

Ever since, the prominence of his clients has only risen: His rolodex includes Winky Wright, Simon Brown, “Sugar” Shane Mosley and, perhaps most notably, Manny Pacquiao, with whom Sternburg worked from 2005 through Pacquiao’s retirement in 2021. His current clients include the pay-per-view livestream service PPV.com, which airs boxing matches, and legendary boxing commentator Jim Lampley.

Boxing has declined massively in popularity over the last half-century or more. It now clocks in as the 13th most popular sport, according to Gallup — behind figure skating and mixed martial arts as well as football, baseball and basketball. But the personalbility of the fighters is what keeps Sternburg in love with the sport, he said.

“There’s so many highlights, and I’ve met so many wonderful people,” Sternburg said. “These fighters, they’re so accessible in terms of athletes — compared to what you see in football, in golf and baseball, everyone’s so protected. These guys just have these compelling stories, and they’re not afraid to share them. It’s just a wonderful experience.”

He’s also won praise for his knowledge of the sport and its athletes. Foreman, now a 43-year-old ordained rabbi living in upstate New York, said Sternburg was the easiest promoter to work with, in large part because of his attention to detail. The two men sharing a Jewish background didn’t hurt, either — Foreman is among the recipients of Sternburg’s annual tradition of sending jars of honey to friends for Rosh Hashanah.

Yuri Foreman, left, exchanges blows with Miguel Cotto during the WBA world super welterweight title fight at Yankee Stadium, June 5, 2010. (Al Bello/Getty Images)

“First of all, I didn’t have to explain nothing to him,” Foreman said. “Because he knows what’s the involvement … and what being a Jew is. So it was almost like a silent agreement between me and him.”

Foreman also had kind words for his publicist as a person. “Fred was always probably one of the most professional people I work [with],” Foreman said. “Always, always on time, always on top of his game.”

That perception goes beyond the fighters. Kevin Iole, an award-winning journalist who has covered combat sports for more than four decades, wrote on his website after the induction class was first announced in December that “nobody was ever more deserving of a Hall of Fame slot” than Sternburg.

“Sternburg’s election was met with resounding good cheer throughout the boxing industry, because he’s not only the greatest publicist in boxing history, but he’s also one of its good guys,” Iole wrote.

Sternburg’s reputation as a “good guy” is a literal one — in 2004 the Boxing Writers Association of America honored him with the Marvin Kohn “Good Guy” Award, named after another boxing publicist. The accolade is mentioned in another document recognizing Sternburg’s standout career: a proposed New York State Senate resolution celebrating Sternburg for his Hall of Fame induction.

As a publicist, Sternburg said he is guided by a commitment to the truth that his parents instilled in him, and that he and his wife have passed onto their own children.

“Honesty is the best policy and that seems to me one of the backbone tenets of Judaism,” Sternburg said. “That’s really what it’s all about, is just treating people the way you want to be treated. And try to do the right thing as best you can.”

Despite all the praise, Sternburg has maintained his reputation for humility and humor.

“I don’t know, maybe it was a bad year and they just needed people, but I don’t think I belong in here,” he said about the Hall of Fame. “But I sure am appreciative that I am. And hopefully we can get this thing done before the recount happens.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.