For many Israelis and their supporters, “sorry” seems to be the right word for the hardest times.

At a vigil Sunday in Jerusalem remembering Israeli-American Hersh Goldberg-Polin and five other Israel hostages whose bodies were recovered the day before, mourners wrote “slicha” — “sorry” in Hebrew — on placards.

At the funeral that day of Eden Yerushalmi, one of those killed, a family member held a sign saying “Slicha Eden” next to her body.

At a vigil in New York’s Columbus Circle that night, another sign: “Slicha. I’m so sorry that the world failed you.”

And at Goldberg-Polin’s funeral on Monday, Israeli President Isaac Herzog apologized for Israel’s failure to free the captives held by Hamas. “As a father and as the president of the State of Israel, I want to say how sorry I am, how sorry I am that we didn’t protect Hersh on that dark day, how sorry I am that we failed to bring him home,” he said, in English, after first speaking in Hebrew.

In those Hebrew remarks, Herzog used the word “slicha,” which in recent days has become another familiar phrase in a nearly yearlong crisis that already has spawned its own vocabulary.

Protesters attend a rally calling for the release of Israelis held kidnapped by Hamas in Gaza outside the prime minister’s office in Jerusalem, Sept. 1, 2024. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

The word, like its English counterpart, can convey a range of meanings — from a casual “excuse me” to a profound request for forgiveness. Appearing numerous times in the Hebrew Bible, the s-l-ch root is related to personal forgiveness.

In Elul, the Hebrew month that began this week and is seen as a spiritual run-up to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, worshippers begin adding “selichot” — penitential prayers — to their daily prayers.

Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie of New York’s Lab/Shul congregation saw and heard the phrase “slicha” repeatedly when he attended Sunday night’s mass demonstration in Tel Aviv calling on the Israeli government to reach a hostage deal.

“The impulse for personal remorse and repair is built into the infrastructure” of Jewish tradition and culture, he said, citing the communal prayers for forgiveness said during the High Holidays. “We feel a collective responsibility for problems and solutions.”

Lau-Lavie said his current trip to Israel inspired him to launch throughout Elul a “public accountability project” in which individuals preparing for the High Holidays can ask themselves, “How are we part of the bigger problem?”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu used the word “slicha” in an apology delivered Sunday to the parents of one of the six slain hostages, Alex Lobanov. “I would like to tell you how much I regret and ask forgiveness [in Hebrew, ‘mevakesh slicha’] for not succeeding in bringing Sasha back alive,” Netanyahu told Lobanov’s parents, according to a readout from his office, using their son’s nickname. Many noted it was the first time Netanyahu had apologized to a hostage family.

Families attend the funeral of slain hostage Eden Yerushalmi, killed in Hamas captivity in the Gaza Strip, at a cemetery in Petach Tikva, Israel, Sept. 1, 2024. The sign reads, “Sorry, Eden.” (Avshalom Sassoni/Flash90)

What makes “slicha” unusual in the case of the hostage vigils is that it is being said by members of the public who seemingly have no direct responsibility for the prosecution of the war, or for the military and diplomatic efforts to free the hostages.

Michal Kravel-Tovi, an associate professor of socio-cultural anthropology at Tel Aviv University, says the impulse to apologize may be in part an expression of survivor’s guilt by Israelis who are able to go about their daily lives while others fight in Gaza, mourn their dead or have family and friends still held hostage.

“I think that it is increasingly linked with the hostage crisis: how we get used to it, continue with our life … while others are dying there. People apologize for being privileged to not be a family member of a hostage,” she said.

Kravel-Tovi is the co-editor of a forthcoming book on phrases that came into wide circulation since Oct. 7, including “ein milim” (there are no words [to convey our grief]) and “beyachad nenatzeach,” or “together we will win.”

She also suggests that mourners and protesters are saying “slicha” out of frustration with a government that hasn’t done enough to bring home the hostages, or didn’t protect its citizens on Oct. 7. Under these conditions, she said, it is civilians who “are the ones to be the moral voice and pragmatic actor instead of the state, are the ones to say sorry — sorry for not doing enough, or being unable to sufficiently succeed.”

A sign at lower left reads “sorry” in Hebrew at a vigil in New York’s Columbus Circle in memory of six Israeli hostages who were found killed in Gaza, Sept.1, 2024. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Lau-Lavie, who grew up in Israel, noted that the current expressions of “slicha” are largely coming from an ostensibly secular segment of the Israeli public, and not from the religious Zionist movement or the haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, community.

“I was talking with a moderately right-wing taxi driver who told me the protests show ‘weakness,’” said Lau-Lavie. According to the driver, Israelis need to apologize because “we are not strong enough.”

Netanyahu’s critics, meanwhile, insist that he hasn’t taken responsibility either for the security lapses of Oct. 7 or the lack of a ceasefire deal that might bring more of the hostages home. Last month, after he told Time magazine (in English) that he was “sorry, deeply, that something like this happened” on Oct. 7, many of his critics found his words, absent a call for a full accounting of what went wrong, inadequate. “He’s sorry, as if he was someone from the United Nations who was unconnected to the event,” wrote Nehemia Shtrasler, a columnist for the left-wing Haaretz newspaper.

Danya Ruttenberg, an American rabbi and author of “On Repentance and Repair,” a book about apologies and forgiveness, said there is a different valence to “I’m sorry” depending on the speaker.

Israelis, holding signs saying “sorry,” protest for the release of Israeli hostages held in the Gaza Strip, outside the prime minister’s official residence in Jerusalem, Sept. 1, 2024. (Chaim Goldberg/Flash90)

When a government official says it, said Ruttenberg, “it’s both a lovely sentiment and kind of meaningless, because what would they have done differently? Is it, ‘I’m sorry I couldn’t have saved your child,’ or is it, ‘I’m sorry that we prioritized X, Y and Z and we should have made other choices’?”

By contrast, “when you have protesters saying it, it’s an acknowledgement that they too are responsible, it’s an owning of that responsibility, and to me that’s beautiful.”

She quoted a line by the late American rabbi, activist and theologian, Abraham Joshua Heschel: “In a free society, some are guilty, but all are responsible.”

“I think it’s exactly that,” Ruttenberg said. “They are acknowledging that they are part of the greater communal body that also failed the parents and families of those who were murdered, and they are taking responsibility.”

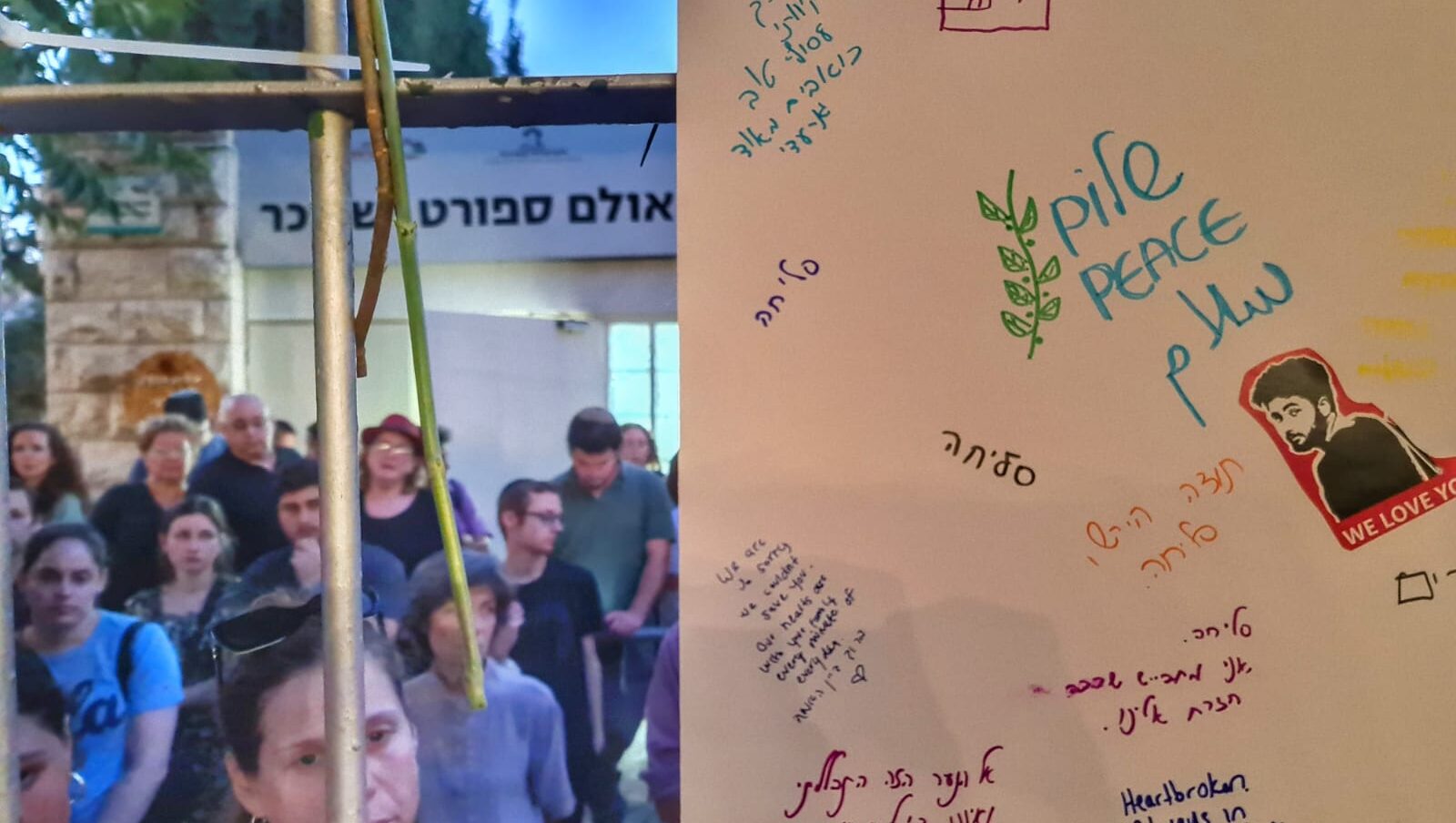

Mourners left notes at a gathering at Hersh Goldberg-Polin’s family synagogue in Jerusalem. Many of the messages used the Hebrew word for “sorry.” (Deborah Danan)

In emotional remarks at her son’s funeral, Rachel Goldberg-Polin used the language of apology in ways that reflected all the anguish and contradictions of the past 11 months.

She recalled how her son texted the family from a bomb shelter on Oct. 7 when he was badly injured and had witnessed his best friend Aner Shapira killed by a Hamas grenade. “You had lost your arm, and you thought you were dying. You wrote to us, ‘I’m sorry’ because you knew how crushing it would be for us to lose you, so you fought to stay alive … all this time. But now, you are gone,” she said.

She also offered her own apology to Hersh, despite spending nearly every day since his kidnapping traveling and lobbying for his and the other hostages’ release. “At this time I ask your forgiveness. If ever I was impatient or insensitive to you during your life, or neglectful in some way, I deeply and sincerely request your forgiveness,” she said. “If there was something we could have done to save you and we didn’t think of it, I beg your forgiveness. We tried so very hard. So deeply and desperately. I’m sorry.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.