For his doctoral dissertation in history at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Yehuda Bauer focused on the British Mandate that before Israel’s independence controlled historic Palestine.

In a conversation with Abba Kovner, the poet who had led the resistance to Nazi rule in the Vilna ghetto, the young historian said he knew there was a larger story to tell but admitted that he was fearful of taking on a subject as monumental as the Holocaust.

Kovner convinced him that there was no more important event in Jewish history and that his fear of the subject was “a very good starting point.”

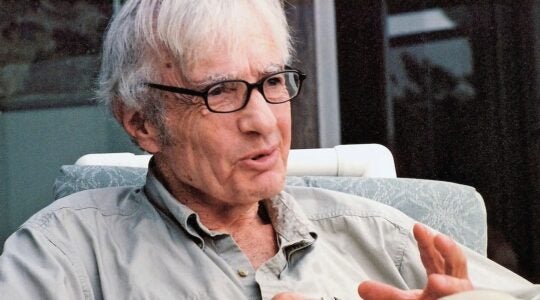

Over the next 60 years, Bauer, who died Friday at age 98, would go on to become perhaps the preeminent scholar of the Holocaust, chronicling in meticulous detail and pointed analysis the destruction of European Jewry, the unprecedented nature of the Shoah and the need to apply its lessons to prevent similar human catastrophes.

Among his groundbreaking books were “Out of the Ashes” (1989), about the American Jewish role in rehabilitating survivors of the genocide; “Jews for Sale?” (1995), about the morally troubling negotiations between Nazi and Jewish leaders in the early years of the war, and “Rethinking the Holocaust” (2001), an overview of the field of Holocaust studies that included sometimes searing critiques of his contemporaries.

“In many ways, the entire field of Holocaust education, remembrance, and research is part of Yehuda’s legacy,” Robert J. Williams, the executive director of the USC Shoah Foundation, wrote in an appreciation this week. ’’For historians of my generation, many of the books we read in graduate school were Yehuda’s contributions. If we were not reading Yehuda, there was a good chance we were reading the works of historians trained and mentored by Yehuda.”

Bauer was also the first advisor to what became the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, an intergovernmental agency founded in 1998 to strengthen Holocaust education and remembrance. Last year, after Bauer announced his retirement as the IHRA’s honorary chair at age 97, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken sent a letter describing the historian as “an example we all want to emulate: someone who speaks the truth about the darkest chapter of our history, and someone who teaches us to look forward as we learn from looking back.”

Bauer was born in Prague in 1926, and with his family left Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939, the same day the country was annexed by the Nazis. The family fled to Poland and Romania before settling in British Mandate Palestine later that year.

Bauer attended high school in Haifa and served in the pre-state Jewish paramilitary known as the Palmach. He studied at Cardiff University in Wales on a scholarship, returning home to Israel to fight in the 1948-49 War of Independence. (Welsh was one of the nine languages he was able to speak.)

He later moved to Kibbutz Shoval and completed his doctoral studies at Hebrew University.

His academic titles included professor emeritus of history and Holocaust studies at the Avraham Harman Research Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and academic advisor to Yad Vashem, Israel’s official Holocaust authority.

In 1998 he was awarded the Israel Prize, one of the country’s top honors, for his lifetime achievements in scholarship. He was also made a member of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities in 2001.

Bauer remained active and outspoken nearly to the end of his life: In 2018, he had harsh words for Israeli officials who settled a diplomatic row with a Polish government that had sought to place limits on what could and could not be written about the Holocaust; in 1992, he challenged the consensus of his colleagues by downplaying the significance of the Wannsee Conference, where top Nazi officials were said to have gathered at a villa in a Berlin suburb in 1942 to draw the blueprints of the “Final Solution.”

“Wannsee was but a stage in the unfolding of the process of mass murder,” he said at the time.

In 1998, Bauer gave a speech to the German Bundestag in which he proposed three additional commandments to the Ten Commandments. “I come from a people that gave the Ten Commandments to the world,” he said. “Let us agree that we need three more, and they are these: thou shalt not be a perpetrator; thou shalt not be a victim; and thou shalt never, but never, be a bystander.”

According to the Associated Press, he is survived by two daughters, three step-children and numerous grandchildren.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.