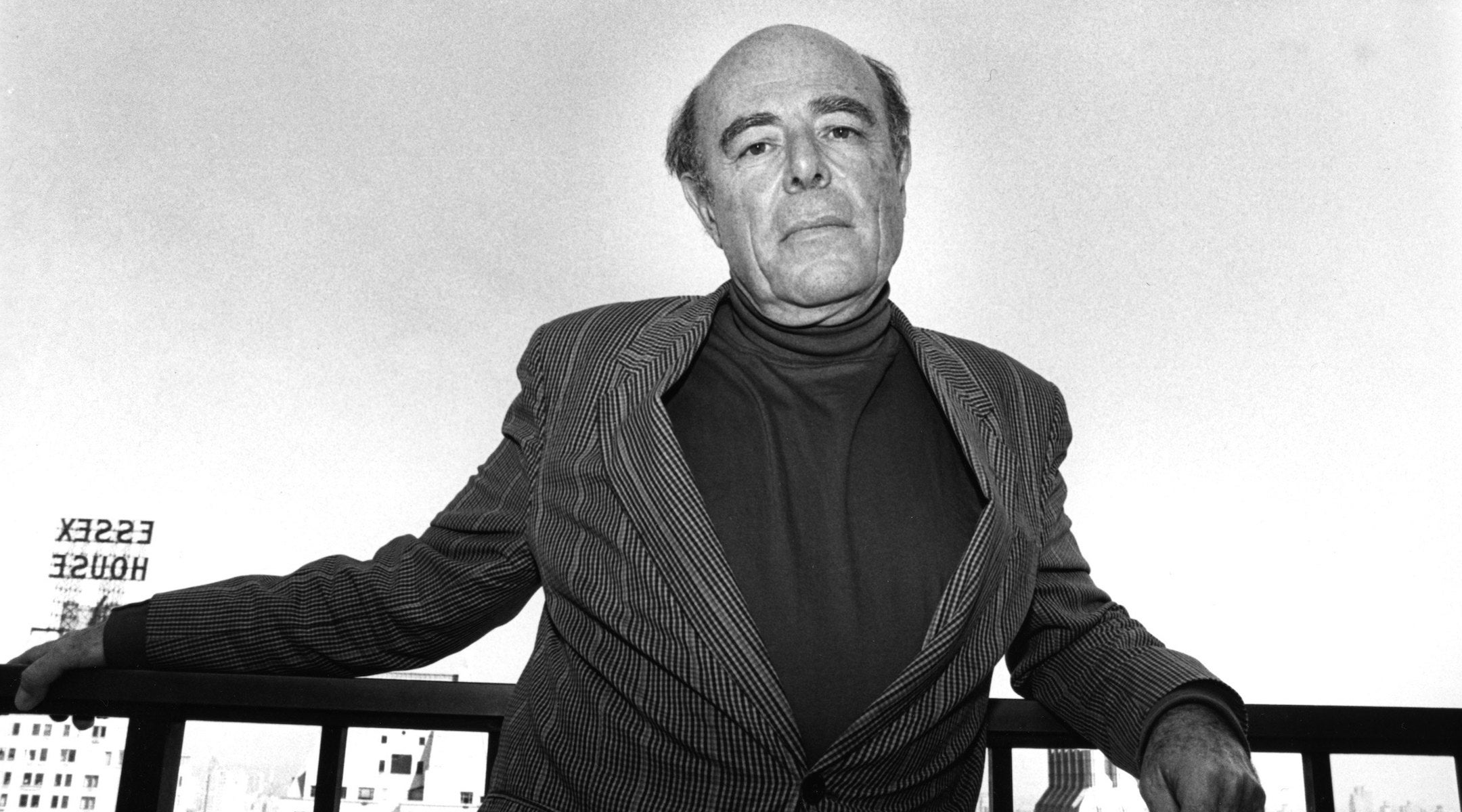

Marcel Ophuls, the acclaimed French Jewish documentary filmmaker whose landmark 1969 film “The Sorrow and the Pity” compelled France to confront its national shame over its collaborationist behavior during World War II, has died at the age of 97.

Ophuls had spent the last years of his life trying to raise the money to complete a new documentary that would have critically explored Israel and Zionism.

Over his long life and career the director made several films exploring historical guilt and complicity, often with a bold and provocative thesis and a willingness to prod his subjects into uncomfortable territory. He returned often to the subject of Nazi persecution, including with his Oscar-winning 1988 film “Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie,” a biography of the Nazi war criminal.

Born in 1927 in Frankfurt, Germany, Ophuls was born into a show business family. His father Max Ophüls was a celebrated filmmaker; his mother Hildegard Wall was an actor. The family fled Germany for France in 1933, when Hitler came to power. But France under Vichy rule also proved dangerous, and the family spent a year in 1940 in hiding before fleeing for the United States via the Pyrenees and a brief stay in Spain.

Ophuls spent his teenage and college years in the United States, primarily in California, where he grew up in Hollywood and attended college at the University of California, Berkeley. The family returned to France in 1950, where his formative experience in Vichy France would prove a key artistic inspiration after he entered documentary filmmaking.

“The Sorrow and the Pity,” which Ophuls made in 1969, hit French society like a ton of bricks. The four-and-a-half hour film explored in tireless detail, and in ways previously unknown or unexplored, the extent to which Vichy France played the role of willing Nazi collaborators — focusing largely on Clermont-Ferrand, a single city in central France. Not only a chronicle of big military actions, Ophuls also interviewed everyday French citizens, including a pharmacist whose answer to the question of what emotions he felt under Nazi rule provided the film’s title.

Though commissioned for French TV, the film was initially too controversial and barred from air. But it had an impact in theaters and entered the popular lexicon, most famously in Woody Allen’s film “Annie Hall” a few years later, in which Allen’s character frequently suggests to his date that they see it.

Ophuls’ other films included the similarly controversial “The Memory of Justice,” which juxtaposed the Nuremberg Trials with American actions during the Vietnam War, and “Munich, Or Peace In Our Time,” exploring the 1938 appeasement agreement between Hitler and Western powers that opened the door for further Nazi invasions. Before entering documentary, Ophuls was an assistant for Hollywood legend John Huston and directed a segment of an anthology film for French New Wave legend François Truffaut.

But in the last decade of his life, he sought to tackle the ultimate subject for Jews: the state of Israel. Together with Israeli director Eyal Sivan, Ophuls attempted to crowdfund to make “Unpleasant Truths,” a film that promised to use the 2014 Gaza war to explore Zionism from a critical lens. French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard, whose own views on Israel proved polarizing in his life, initially planned to help them make the film before backing out of the project.

In 2016 the pair released some in-progress footage from the film, in which Ophuls journeys to Tel Aviv in the midst of the war to interview Israelis, including West Bank settler leaders, and other pro-Israel visitors who espouse racist views on camera. Ophuls himself, on camera, says Palestinians are living under “apartheid” and shares his belief that Jews should be “against nationalism.” Explaining his vision for the documentary, Ophuls tells Sivan that Jerusalem “should be like Clermont-Ferrand in ‘The Sorrow and the Pity.’”

The film was never finished.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.