Miri Bar-Halpern and Jaclyn Wolfman don’t use the term “gaslighting” in their paper on Jewish trauma after Oct. 7, but they might as well have.

The Boston-area trauma therapists, writing in the Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, give a different name to the pain many Jews have felt over the last harrowing 20 months: “traumatic invalidation.” It’s a common term in their field, describing when, for example, rape victims are told they have “misinterpreted” events or even brought them on themselves.

They apply the term to what Jews have reported in the months after the Hamas attacks: “Rather than being met with compassion and care,” they write, “many were instead met with a stunning mix of silence, blaming, excluding, and even outright denying the atrocities of Oct. 7 along with any emotional pain stemming from them.”

For the Jews in their study, “traumatic invalidation” took the form of colleagues who ignored or shunned them after Oct. 7, or suggested that Israel had it coming, or told them that they were “overreacting” to antisemitic comments.

They write of clients and colleagues excluded from clubs and professional associations, pelted with pro-Hamas messages from people they considered friends, and told that their grief over the deaths, kidnapping and sexual assault of Jews after Oct. 7 does not matter compared to the human toll in Gaza.

Individuals whose experiences are invalidated or downplayed can be at risk for a range of symptoms, including mood swings, anxiety, depression and even post-traumatic stress. Making it worse, they write, are therapists and counselors who either don’t appreciate their Jewish clients’ pain or who minimize their distress.

Posted last month by a journal for specialists — part of a forthcoming issue on antisemitism and social work — the paper by Bar-Halpern and Wolfman has been shared widely on social media.

”We’ve been getting a lot of messages and emails saying just, ‘Thank you for giving me the language,’” said Bar-Halpern in a joint interview with Wolfman this week. “We had one person saying that she was crying while reading it, because she finally felt validated after the last year and a half and things finally made sense to her.”

Bar-Halpern, 41, is a clinical psychologist, a lecturer at Harvard Medical School and director of trauma training and services at Parents for Peace, a national helpline for U.S. families with children drawn to extremism of all kinds. She grew up in Israel and moved to the United States 17 years ago.

Wolfman, 45, is a Harvard-trained clinical psychologist who grew up in Connecticut. She is founder and director of Village Psychology in Belmont, Massachusetts.

In a Zoom call, they spoke of the hurt inflicted when others deny your pain, how therapists fail their Jewish patients, and the kinds of skills that build resilience.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start by telling me how you came to this topic.

Miri Bar-Halpern: On Oct. 7, 2023 I wrote a message on a Massachusetts Israeli group [chat] saying, “This is my cell phone number. If anybody needs support, give me a call,” and I’m flooded with phone calls. So I quickly mobilized a team of Hebrew-speaking clinicians, and for about a year, we provided free support for Israelis in Massachusetts. And then it got wider. I started hearing those stories from the people that I’ve been seeing even for one session, because they have their own therapist, and the narratives were very similar to what I’m seeing in my clinic.

In other words, clients coming to you because they felt their own therapists either dismissed their concerns or couldn’t understand what they were going through as Jews?

Bar-Halpern: 100%. If you look at listservs right now, people actually say, I, “I’m looking for a Zionist therapist. I’m looking for a Jewish therapist.” They’re looking for someone that they can relate to, which, in the past, wouldn’t be an issue.

Wolfman: Along those lines, I saw someone who had stopped attending synagogue in person for fear of violence and had never brought it up with their previous therapist. And so we find things like that too: Certain things aren’t being asked about because [therapists] don’t know to ask, or maybe somebody doesn’t feel safe to share it, because they don’t know how it’s going to be received, if it’s going to be dismissed, if it’s going to be minimized.

The antidote to that is education, training and experience, and that’s part of what we want to be able to offer to people.

Can you give me examples of Jewish clients who felt either invalidated by friends or gaslit by their therapists?

Bar-Halpern: One individual was part of the LGBTQ community. This is actually that story that really made me realize we need to write this paper. This individual, for years, had been going to an LGBTQ group, and after Oct. 7, they said that the facilitator of the group started coming with a keffiyeh to the group, and the artwork [at their office] became “from the river to the sea,” “globalize the Intifada,” a map of Israel with a Palestinian flag on it. They actually told the facilitator that it doesn’t make them feel safe, that they lost people on Oct. 7. And the group facilitator said, “You’re just going to need to deal with it. This is social justice.”

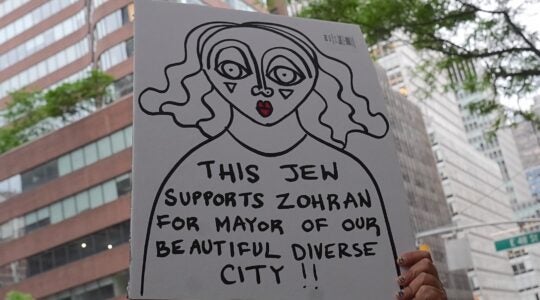

The defacing of hostages posters, like these seen in midtown Manhattan in November 2023, “can be seen as a way of ignoring the pain of their families and erasing their narratives,” write the authors. (Luke Tress)

Were you able to help?

Bar-Halpern: I ended up calling the director of this practice and told them, “You’re causing harm. It’s not ethical. When a client is telling you, ‘You’re causing me harm,’ then it’s not ethical.” And their answer was, “Oh, I can see how that can be looked from two different perspectives.”

Wolfman: A young adult talked about posting something in support of the Jewish community, and said, “Now I’m getting all these hateful messages from people I went to college with. Did they always think this about me?” And it made her question her whole social circle and her relationships, and how she fit into her various communities. She was really caught off guard and surprised, because she would have expected, after the worst massacre of Jews in a single day since the Holocaust, that she would have been met with compassion, with care, with understanding, at least with curiosity. But instead she was met with a lot of criticism, blaming and unequal treatment.

Is there a risk of turning discomfort and disagreement, inevitable in a polarized country, into trauma? I am thinking of the young adult whose one-time allies have taken the pro-Palestinian side. It’s uncomfortable, certainly, but is it really useful to treat this as a mental health challenge?

Wolfman: Disagreement is welcome and necessary. Traumatic invalidation isn’t disagreement; it’s ignoring, or blaming, or unequal treatment. Traumatic invalidation sends the message that the other person is bad or unacceptable as a human being. It’s an attack on one’s sense of self. That’s very different from having a difference of opinion or worldview. Respectful disagreement can actually feel very validating when you sense that the other person sees you and treats you as an equal and valid human.

The last few weeks have seen the killings of two Israeli embassy staffers outside the Capital Jewish Museum and the firebombing attack on the Boulder, Colorado march for Israelis taken hostage. Are your clients and colleagues talking about these attacks in ways that fit into your invalidation framework?

Bar-Halpern: For me, it goes back to the dehumanization piece, into normalizing hate and normalizing invalidation. The Jewish community has been saying, “We’re afraid this might happen, and nobody is saying our pain is real, and nobody’s taking us seriously.”

I’m assuming you write a paper like this because you want to alert your colleagues. What are you hoping to accomplish by getting it out in the world?

Bar-Halpern: I wanted to give people the language to describe how they’ve been feeling and give them that stamp of approval in an academic peer-reviewed journal.

The other part of it was a call for action. The mental health community has failed the Jewish world these days. They’re not providing the same type of care that I would like to see generalized to every group that is suffering right now. I mean, if you look at Facebook groups or social media groups or even listservs of therapists, it’s pretty brutal to see how they’re questioning the trauma. We’re not asking for a special treatment. We’re just asking for the same type of care you would give any type of client that is telling you. “I’m hurt, I’m in pain, I’m scared.”

Wolfman: What’s really important is that, as a mental health provider, you’re trying to understand the world from your client’s perspective, and to put that understanding into words. Validation does not mean agreement. You don’t have to agree to be able to validate and understand where that person’s experience is coming from.

What’s important is really being open and curious to what your client is trying to communicate to you and sitting with it and then reflecting it back to them in a way that helps them then understand themselves better, regulate their own emotions, and then being able to better articulate their own experience to themselves and to others.

Bomb squads set up a staging area after a suspect threw homemade firebombs at a group of marchers raising awareness of the plight of Israeli hostages, Boulder, Colorado, June 1, 2025. Said Miri Bar-Halpern: “The Jewish community has been saying, “We’re afraid this might happen, and nobody is saying our pain is real, and nobody’s taking us seriously.” (Chet Strange/Getty Images)

Are there skills you teach that help clients with their feelings of trauma and isolation?

Bar-Halpern: I would do what we call “cope ahead” for future invalidation, for future situations that they might get invalidated or might not get invited to a party because they’re Jewish, which happened multiple times. So we try to cope ahead for that as much as we can, while acknowledging that we cannot cope ahead for everything.

Particularly important to coping ahead in the long term would be finding a new sense of belonging and connecting to a community, whatever community that is connected to their own values. It doesn’t have to be a religious community, or necessarily just a Jewish community — even though we did see that when people are more connected to the Jewish community, they do feel more validated — but a connection to something, because there’s so much loss.

Your paper was posted last month. Tell me about some of the reactions.

Wolfman: Overwhelmingly positive. People saying, “Wow, this is everything we’ve been talking about and thinking and feeling put down in print. I feel so much better having read your paper.” The title alone, “Traumatic invalidation in the Jewish community after October 7,” can capture a lot of what people are feeling. And again, it’s the power of naming something and being able to then understand and work with it.

Bar-Halpern: I’ll mention one experience that was negative and positive. There is a listserv for the [Dialectical Behavior Therapy] community and for the last year and a half it’s been rough. They’ve been very much invalidating a lot of the Jewish experiences, and a lot of Jewish clinicians were trying to speak up and were shut down. And when [the paper] was posted on that listserv, the immediate reaction of one of the people was, “I thought we’re not talking about the war anymore.”

On the other hand, someone responded and said, “This is not about the war. This is about the Jewish experience in the United States.” On that listserv, a therapist who’s not Jewish said that this paper made them broaden their ability to understand the Jewish experience and validate more than they thought they’re capable of, and that it gave them ability to really support their Jewish clients better. If we move the needle for one person, then we did our job.

What else do you want people to understand about traumatic invalidation that we haven’t touched upon?

Bar-Halpern: I really want to make the case that it is not just a Jewish problem. When you start dehumanizing any type of group, you’re going to dehumanize other groups as well. If we look at everything as a hierarchy of pain, we don’t see people as people. Then we’re losing our humanity, and especially as therapists.

Wolfman: One of the things that I’ve seen throughout the last couple of years is a lot of hope, a lot of connection, a lot of growth. I think that’s really important to acknowledge as well: We can validate each other and find those supportive communities, and make meaning from our experiences alongside the grief and pain that a lot of us have been feeling and continue to feel.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.