I always thought it would be the left who would come after me.

I thought that someone in one of my artistic circles (or what’s left of them) would bring me down for being too Zionist, too Jewish, not liberal enough, not progressive enough, not voting for the right person, or not being vocal enough against the wrong person.

Little did I imagine my banishment would come from the other side.

It started innocently enough, with me doomscrolling instead of working, half-heartedly liking posts on the ancient bulletin board that is Facebook, making an innocuous comment here, asking a question there, without paying that much attention.

Perhaps I should have been.

Apparently, I said the wrong thing on a post in the group Mothers Against College Antisemitism. Now boasting 61,000 members. MACA was started after Oct. 7 to help parents (“not just mothers,” my husband said, annoyed at the exclusion) navigate where to send their Jewish kids to college in these tumultuous times.

I don’t have a kid nearing college age, but after Oct. 7 I joined a number of pro-Jewish groups to both feel supported and to possibly report on them for the various Jewish publications I wrote for after the war (including this one).

So I watched as MACA became an active forum for blowing the whistle on anti-Zionist professors, calling out colleges and administrators for not seeming to act forthrightly enough in combating antisemitism and sharing allegations of antisemitism.

At times the group teamed up to lobby against particular clubs, courses or instructors that ignited members’ concerns; sometimes, the allegations reflected activities beyond college campuses. In the case of the post I responded to, the concern was the attire of an employee at a public park. The poster was updating the group after previously issuing a call to action.

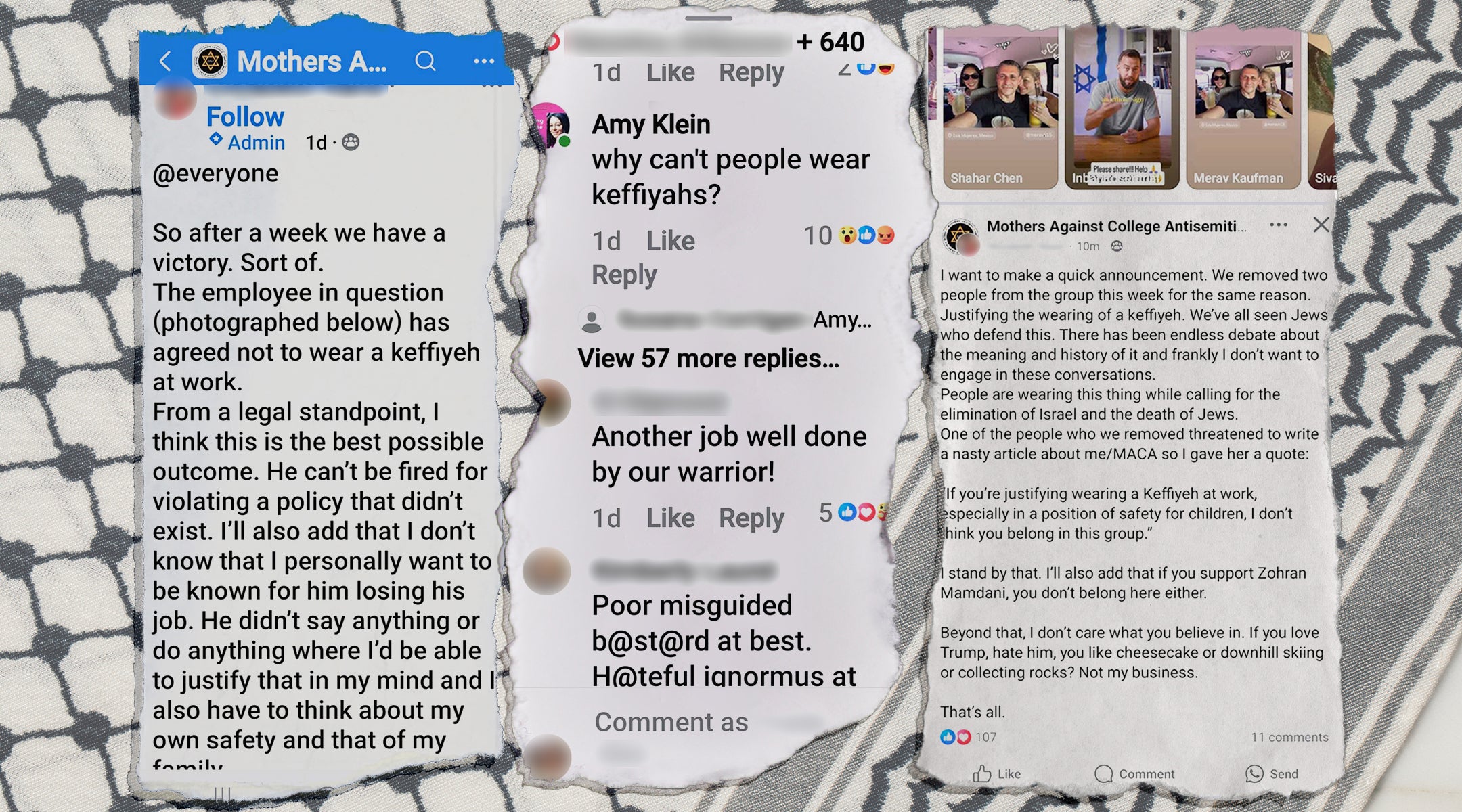

“So after a week we have a victory. Sort of. The employee in question (photographed below) has agreed not to wear a keffiyeh at work,” the poster wrote. She continued, “From a legal standpoint, I think this is the best possible outcome. He can’t be fired for violating a policy that didn’t exist. I’ll also add that I don’t know that I personally want to be known for him losing his job…”

There was more to read but I didn’t continue, because I was shocked and confused. I wrote, “Why can’t people wear keffiyehs?”

I probably should have known that the keffiyeh, a traditional Palestinian scarf adopted by anti-Israel protesters, has become triggering to many Jews. But I didn’t. And I couldn’t learn that perspective from the group, because I had been booted from it.

Keffiyehs, the Palestinian shawl, have become ubiquitous in many public places after widespread protests against Israel’s war in Gaza. (Illustration by Grace Yagel)

Friends in the group — who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals — sent me screenshots of the hundreds of comments after mine. “For the same reason Buddhists stopped wearing the swastika symbol in public. Not their fault of course but it just means something completely different now,” read one. Another commenter wrote, “Wearing a swastika is legal too. Does not change the fact that they both have the exact same meaning. KILL THE JEWS.”

Some of the comments excoriated me personally. One commenter called me part of the “pro-keffiyeh clan,” and another said that my “boorish question” was devastating. “That we have to fight our own is grotesque,” the commenter wrote.

Instead of giving me a chance to explain that my question was genuine, or to learn why so many others in the group had a different reaction, I was kicked out immediately. The quick ejection felt like a sign of these divided times, which have left Jews like me stranded.

A group administrator said I was removed from the group for not answering the admission questions and could complete them again to regain admission. The questions included “Are you a Zionist?”

So I went back and answered: “I am a naturalized Israeli citizen, married to an Israeli-born citizen, and a longtime Jewish journalist covering religion and Israel for publications like The Jerusalem Post, The New York Post, JTA, Hadassah, Haaretz, The Forward, CNN and others.”

What I did not say was, “I went to yeshiva for all my schooling, lived in Israel, send my daughter to Jewish day school, work for Jewish organizations and spent much of my time after the war sending money and equipment to soldiers in Israel.” (“Her pedigree is completely immaterial,” one man wrote about me.)

So far, I have not been readmitted. If I am not good enough for this group, who is? If I cannot pass some invisible litmus test — where the bar keeps changing — who can?

“If you’re justifying wearing a Keffiyeh at work, especially in a position of safety for children, I don’t think you belong in this group,” the admin wrote me.

Perhaps not.

Members of the Palestinian embassy to the Holy See give a keffiyeh, a traditional Palestinian scarf, to Pope Francis during a Christmas ceremony at St Peter’s Square at the Vatican, Dec. 7, 2024. (Andreas Solaro/AFP via Getty Images)

Listen, it doesn’t really matter if, to paraphrase Groucho Marx, I am a member of a group that doesn’t want me. I’ve been booted before: In June 2020, in what seems like more “innocent times,” I was kicked out of a local mom’s Facebook group (40,000) members after reporting about how Black Lives Matter racial tensions were breaking apart moms’ groups.

But the latest eviction has me worried for the Jewish people — and the world.

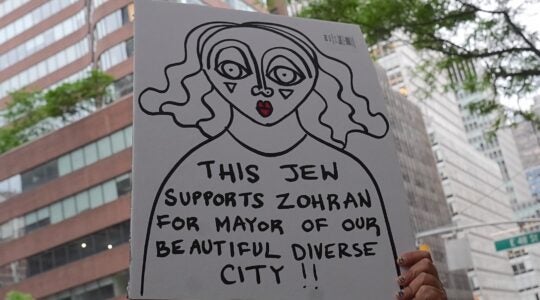

Ezra Klein had it wrong in his recent New York Times op-ed, “Why American Jews No Longer Understand One Another,” when he painted a sharp divide between pro-Israel Jews and Jews who are anti-Zionist or have lost faith in the Jewish state. Klein cited Zohran Mamdani’s candidacy for New York City mayor as the latest wedge between these factions.

I wish it were so clean cut, that I could fit in nicely into one side, either with my ultra-Orthodox family on the right, or my liberal anti-Trump friends on the left. (I’ve learned that one non-Jewish friend isn’t talking to me for me posting a piece critical of Mamdani’s socialist politics, so I’m literally losing friends right and left.)

But I’m one of the many Jews in America and Israel stuck in the middle. We may not love Trump or Bibi but are grateful for America’s support in the war against Iran and the outcome. We New Yorkers may not have voted for Mamdani, but are not thrilled by the nose-holding choices of Eric Adams or Andrew Cuomo. We may not like the continuing war in Israel and the destruction in Gaza, and abhor the hostages not being free, but we also fear the growing antisemitism in America. Half of my Facebook feed is Israelis protesting the war in Gaza and the other is soldiers in uniform fighting for Israel.

And yet on the right and the left, there is no room for nuance anymore. Sometimes, there isn’t even room for a simple question.

Not in the Jewish community and not in the world.

Even Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — hardly known for her pro-Israel support — suffered from this when she received death threats and her office was vandalized reportedly because she voted against an amendment that would have cut funding for Israel’s aerial defense system (even though she voted against the overall bill that included the amendment).

Groups on both sides take an all-or-nothing approach to politics: Either you accept everything we stand for or you don’t belong. If you’re MAGA, you don’t question the conspiracy theories surrounding Jeffrey Epstein. If you want to call yourself a progressive, you must denounce Israel.

Or if you say you are pro-Israel, you don’t question what the group believes to be true about a Palestinian headscarf. As the founder of MACA explained in a post, “We removed two people from the group for the same reason. Justifying the wearing of a keffiyeh. We’ve all seen Jews who defend this. There has been endless debate about the meaning and history of it and frankly I don’t want to engage in these conversations.”

We Jews need to do better. We need to be able to have these conversations among ourselves without name-calling, banning or excommunication.

Otherwise, who will we be and what will remain of us?

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.