When some of Rabbi Mia Simring’s congregants named themselves The Very Narrow Bridge Congregation, they weren’t just referring to the anthemic Hebrew song “Gesher Tsar Meod” or the teaching from Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav on which it is based.

They were also alluding to their status as inmates on Rikers Island, New York City’s largest jail.

“Everybody there knows that they are separated from the rest of their lives by an actual very narrow bridge,” Simring said.

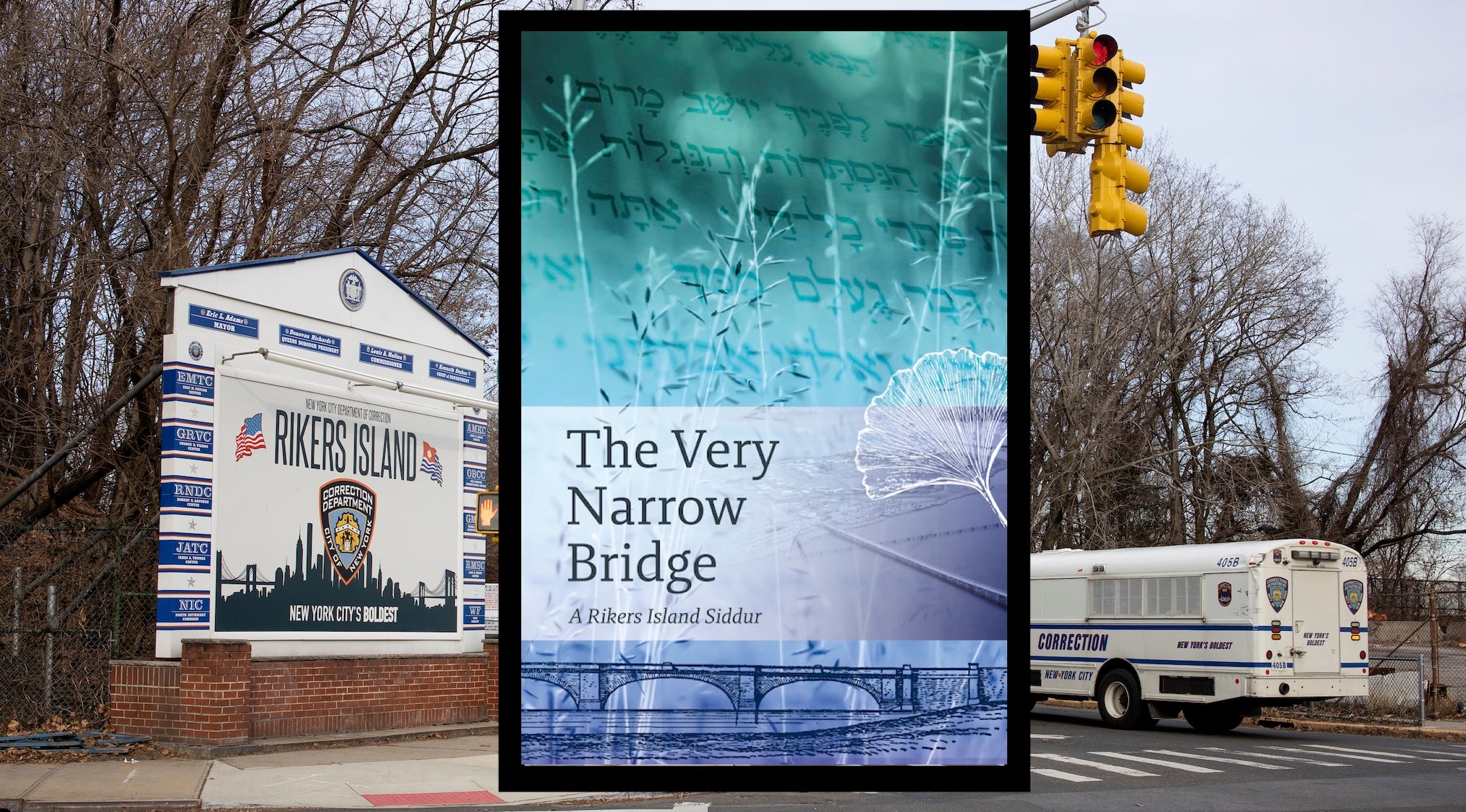

So when it came time to name the jail’s new siddur — perhaps the first ever Jewish prayer book compiled expressly for the use in a correctional facility — the choice was obvious. “The Very Narrow Bridge: A Rikers Island Siddur” entered use earlier this summer.

The one-of-a-kind siddur features bright colors, bold text and an amalgam of Hebrew, English, Russian and Ladino prayers, as well as meditations on healing and recovery and poems by individuals currently or formerly in custody at Rikers.

It replaces what Simring’s colleague, Rabbi Gabriel Kretzmer-Seed, called “photocopied packets for prayer” that the two Department of Corrections Jewish chaplains long cobbled together to try to meet their diverse congregants’ emotional and spiritual needs.

The prayer book was dedicated twice in June: during a ceremony on Rikers attended by DOC First Deputy Commissioner Francis Torres, and at the publication launch at Manhattan’s Central Synagogue, a few miles and a world away from the jail that houses more than 7,000 people and is on the verge of federal receivership because of its poor conditions.

(L-R) Rabbi Mia Simring, Rabbi Hilly Haber, and Rabbi Gabriel Kretzmer-Seed celebrate the launch of a Rikers Island prayer book at Central Synagogue, June 11, 2025, in New York City. (Courtesy New York Jewish Coalition for Criminal Justice Reform)

On hand were representatives of the New York Jewish Coalition for Criminal Justice Reform, a nonprofit that helmed the project, and its funders, including JCRC-NY, the Revson Foundation, the NY Board of Rabbis and Central Synagogue. They understood the long and winding path to create a prayer book that could meet the mix of Jewish, Jewish-curious and non-Jewish individuals who attend services on Rikers.

According to Kretzmer-Seed, the idea for the siddur project began in 2022, when Rachel Lissy, then-director of the coalition, along with Rabbi Bob Kaplan of the JCRC-NY, visited Rikers and attended one of the prayer services.

“The visit was a good catalyst,” said Kretzmer-Seed, noting how it sparked a partnership between the chaplains and the coalition and helped to bolster the prayer services by recruiting other volunteers from the “outside.”

For Lissy, however, what stood out was the condition of the prayer packets.

“The handouts were dispensable and disposable,” said Lissy, who said she saw an effect on the Rikers congregants: “Their spiritual dignity was not being honored.” She began advocating for a more substantive prayerbook for the jail’s services.

The chaplains had had difficulty finding a standard prayerbook that would match the varied needs and backgrounds of their congregants, most of whom have little knowledge of or familiarity with Jewish practice.

Although there are other Jewish organizations who work with Jews who are incarcerated, most use traditional or Orthodox prayer books from publishers such as Chabad and Artscroll. One of them, the Chabad-affiliated Aleph Institute, said in a statement that the new Rikers siddur reflected an important focus for Jewish attention.

“We are aware of the Rikers Siddur Project led by the New York Jewish Criminal Justice Coalition, of which we are proud to be recent members, and we are happy to see other Jewish organizations supporting this often-overlooked population,” the group said.

And so began a year-long project, guided by Lissy’s successor, Cynthia Johnson, to develop a prayerbook that would serve as a stable permanent spiritual resource and honor the dignity of those “in exile” within the vast Rikers jail system.

The effort involved transcending denominational lines. Simring is a Conservative rabbi while Kretzmer-Seed is Orthodox.

Kretzmer-Seed also noted that the idea behind the siddur’s development was to make a resource that “not only recognized the diversity and our own backgrounds as rabbis, but also the diversity of our congregations in our communities.”

Rabbi Bob Kaplan of JCRC-NY speaks at an event to dedicate a prayer book for use on Rikers Island, at Central Synagogue in New York City, June 11, 2025. (Courtesy New York Jewish Coalition for Criminal Justice Reform)

Although the chaplains were in agreement on including core pieces of Jewish liturgy, such as the Shema and Ashrei, they each wanted to include specific prayers that were particularly meaningful to them.

For Simring, it was important to include some of the daily morning blessings that express gratitude, and a prayer she had found for those coming out of rehab after struggling with addiction, trauma and being in or coming out of jail.

Kretzmer-Seed felt strongly about the inclusion of psalms from the Hallel service as well as a Spanish-Portuguese prayer for those in captivity, which was originally written for victims of the Spanish Inquisition.

“Gabe and I have different things that we feel really attached to, but both of us are trying to craft a service that speaks to everybody where they are,” Simring said.

She described how the siddur represents that intention in addressing the diversity of their congregants. “This siddur is both meaningful and accessible to a broad swath of people — from Orthodox to secular, from people from insular Jewish communities to unaffiliated Jews — to people who have lived adjacent to Jewish communities, people who are learning about Judaism for the first time, or even meeting Jews for the first time,” she said.

What also makes the Rikers siddur different from others is the inclusion of writings by those of other faiths who have turned to Judaism while on the island.

The formerly incarcerated poet Miguel Martinez has a poem, “Excerpts from a Letter,” included in the prayer book. Written while he was on Rikers, he described how his loneliness receded as he found connection with those in the Bible. “My journey was never alone,” he writes. “I have David, Saul, Abraham, Lot, and the All-Mighty with me every step of the way.”

As Martinez told the crowd at the Central Synagogue launch, he was on a path to self-destruction but found a lifeline at Rikers through his connection to the chaplains and immersion in Jewish learning. No longer in custody, he continues to attend Jewish services and is now on a path to conversion.

“The transformation I’ve experienced is nothing short of miraculous, a testament to the power of the Jewish tradition and the unwavering compassion of those who live its values,” Martinez said.

“It’s why I felt compelled to contribute to the Jewish siddur, to add a page that reflects the profound shift within me,” he added. “My hope is that it serves as a beacon of positive, uplifting, and inspirational thought for anyone who opens its pages, a reminder of the powerful and awesome capacity for renewal that lies within each of us.”

In addition to the range of spiritual components, the siddur is unusual for its use of colors — blues, purples and other rich hues that are layered over ancient Hebrew text. The use of vibrant colors and natural imagery was deliberate, according to the chaplains, and decided in consultation with Johnson and prayerbook designer Rachel Jackson.

Kretzmer-Seed said the goal was to “have as much color as possible, in a place where there is not always so much color or light.”

Jackson — a bookbinder, artist, calligrapher and one of a small cohort of female Torah scribes — said she welcomed the opportunity to create a ritual object of beauty for people who don’t have access to the richness of the outside world.

“How things look, particularly in ritual and prayer, can have a big effect on … the headspace that people are in,” said Jackson, who said she found meaning in drawing upon photos of prayers from turn-of-the-century prayerbooks that she inherited from her great grandparents. “And so this felt really special in that regard, to be able to sort of create what hopefully feels like an oasis amidst a very difficult place.”

For both Kretzmer-Seed and Simring, the beauty of the new siddur also represents a kind of gift to their congregants, who have access to only a few personal objects.

“The value of something beautiful and something colorful cannot be understated,” said Simring, “and having something you can hold in your hands.”

Correction: This story has been corrected to show that while Rikers Island is on the verge of federal receivership, it has not yet left the city’s oversight.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.