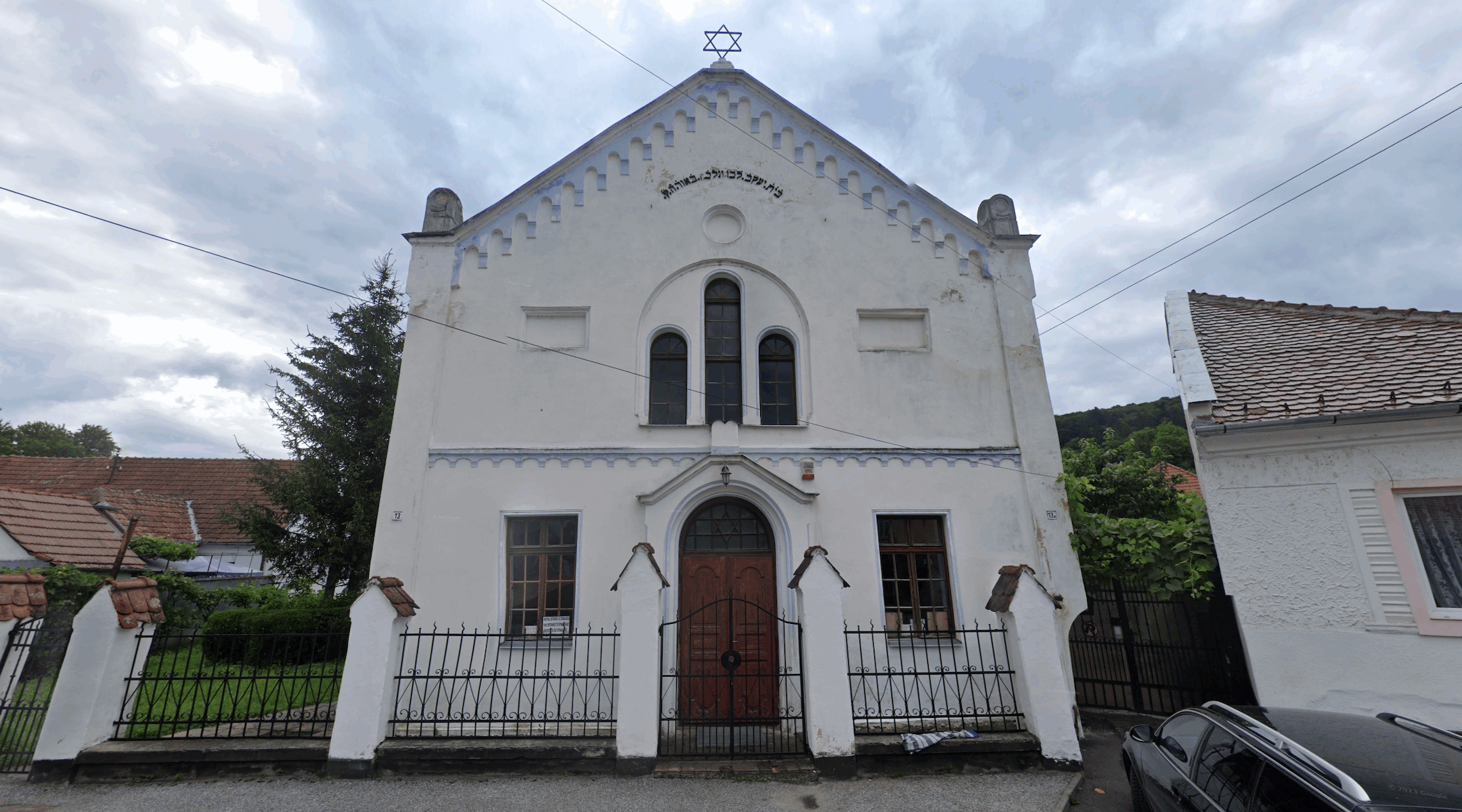

SIGHIȘOARA, Romania — Only a 10-minute stroll down a maze of cobblestone streets from the birthplace of Vlad Dracul — who inspired the fictional, bloodsucking Count Dracula — sits an empty but remarkably well-preserved synagogue in a fairy-tale town that no longer has any Jews.

Built in 1903, the Sighișoara Synagogue was, for a time, the spiritual center for roughly 200 Yiddish-speaking Jewish families. But the Holocaust claimed most of them, and the few who survived World War II eventually left for Israel. In 1984, the last prayer service took place, and the sole remaining Jew — a lawyer named Radicanu — died in 2009.

Around that time, an American lawyer, David Blum, financed the renovation of the building at 11 Tache Ionescu St. in memory of his parents and grandparents. Since then, Viorica Baluța — an Orthodox Christian who lives next door — has been entrusted to care for the building.

“He invested so much money that it would be a shame if this place fell apart,” Baluța, 73, said of Blum. “Sighișoara is a tourist town, and lots of people come here from all over the world, regardless of their religion. People appreciate this synagogue, even if they aren’t Jewish.”

Yet not everyone does. In 2014, vandals tried to set fire to the shul, noted for the whimsical palm trees painted on either side of the ark, and its ceiling, which resembles a starry night. The following year, two teens spray-painted the entrance door with swastikas.

And that was long before the current war in Gaza sparked a wave of antisemitism throughout much of Europe including Romania, which has a poor track record of protecting its Jews.

“It’s getting worse for sure,” said Alexandru Muraru, a member of Romania’s parliament and vice-president of its National Liberal Party, who is not Jewish. “In Western Europe, they have big Muslim communities, which generates antisemitism. In Romania, there are only one or two mosques, but our antisemitism has historical roots.”

Indeed, it does. In the 1930s, Greater Romania was home to some 800,000 Jews — giving it the world’s fourth-largest Jewish population after the United States, Poland and the Soviet Union.

“Back then, Jews made up an important proportion of Romanian society,” said Gilbert Șaim, who’s been the gabbai, or custodian, of Bucharest’s famous Choral Temple for the last 10 years. “Despite widespread discrimination, there were villages, towns, and cities with large Jewish majorities — even villages established by ethnic Jews centuries ago, like Podu Iloaiei.”

A group of Romanian Jews departs Vienna for Israel in 1950. (Photo by David Rubinger/Corbis via Getty Images)

Around half of Romania’s Jews, roughly 400,000 people, were killed by the Nazis and their local collaborators — a statistic cited by a trilingual monument in the Choral Temple’s courtyard. In Iași alone over a three-day period in June 1941, more than 13,000 Jews — more than a third of the city’s Jewish population — were massacred, marking one of the worst pogroms of World War II.

Even so, Șaim said, a 1947 census showed 167,000 of Bucharest’s 650,000 residents still identifying as Jewish. At that time, the capital had around 150 functioning synagogues. But in the ensuing years, many young Jews emigrated — particularly during the 24-year Ceaușescu dictatorship, which allowed 1,500 Jews to leave every year from 1965 to 1989 in exchange for cash payments of between $2,000 and $25,000 each, plus Israeli military assistance to Romania.

Leaving offered Romanian Jews the only chance to preserve a Jewish identity in an era when communism was aiming to quash religious expression.

“Communism did what the fascists and Nazis didn’t manage, to make an entire community nearly disappear,” said Muraru, 43, whose grandfather survived the Iași pogrom. “These days, you cannot imagine a state selling its own people in order to receive money and weapons. But for a country that suffered a lot, like Israel, it was important to bring everyone home. Less important was how they did it.”

By the time Ceaușescu was overthrown and executed in 1989, only 11,000 Jews remained in Romania. And today, barely 2,500 Jews live in this country of 19 million, said Șaim, who at 52 is among his congregation’s youngest members; the rest, he said, are mostly in their 80s and 90s.

Alexandru Florian, director-general of the Bucharest-based Elie Wiesel National Institute for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania, said only 20% of Romanians know about the Holocaust or its wartime role under pro-Nazi puppet Ion Antonescu.

“Antisemitism is exploding on social media, Facebook, TikTok and Telegram, though less visible in traditional mass media. The COVID pandemic amplified conspiracy dating back to the late 19th century,” he said, adding that despite a ban on glorification of Nazi heroes, “at the end of November 2024, there was a public ceremony to commemorate a fascist leader. Those who participated are under criminal investigation.”

Added Muraru: “The extreme right was very powerful here in Romania in the 1930s. And today, these extreme parties present themselves as mainstream, and sometimes they try to legitimize themselves by attending Jewish events or conferences in Israel. This is a very worrying trend given the fact that our parents and grandparents were deported or killed by such people.”

Those fears were recently exacerbated by the 2024 presidential aspirations of Calin Georgescu — a far-right candidate representing the Alliance for the Unity of Romania party, known as AUR, and a self-avowed admirer of Romania’s rabidly antisemitic Legionnaire Movement of the 1930s. The party drew criticism in 2023 after calling the Holocaust “a minor topic.”

George Simion, president of Romania’s right-wing AUR party, attends a protest about COVID-19 rules in Bucharest, Dec. 21, 2021. (Daniel Mihailescu/AFP via Getty Images)

Romania’s Supreme Court cancelled that election, citing concerns about Russian interference, and Georgescu was replaced on the AUR ticket by George Simion, a populist who opposed Romania’s commitments to NATO and the European Union.

In the May 2025 runoff, centrist candidate Nicușor Dan, the mayor of Bucharest, defeated Simion with 54% of the vote — a margin too narrow to calm Muraru’s concerns.

“It was a major victory for Romanian democracy, but as Americans say, we’re just buying time,” he said. “I don’t know if we bought three years, five years or 10 years. But imagine that 5.3 million Romanians voted for an extremist candidate who is also very violent.”

Andrei Dumitrescu, 43, manages a classic car museum across the highway from Bucharest’s international airport. He grew up in the Israeli city of Haifa but came back to Romania, where he was born, at the age of 18, he said, because life was so hard there.

“I don’t think Nicușor is the greatest president, but he was better than the alternative,” Dumitrescu said. “I would never believe that in 2025, we’d be worried about fascism. The problem is that people don’t know history.”

Alexandru Florian, director-general of the Elie Wiesel National Institute, displays a blueprint for the planned National Museum of Romanian Jewish History and the Holocaust. (Larry Luxner)

To that end, Florian’s institute is planning a National Museum of Romanian Jewish History and the Holocaust to be located in central Bucharest. The seven-story, 10,000-square-meter building, projected to cost $50 million, will trace the trajectory of Romania’s Jews from the time of the Bar Kochba Revolt in 135 C.E. to the present day. It’s expected to be completed by 2029 — though fundraising has been slow-going.

Klaus Iohannis, Romania’s president from 2014 to 2025, recently endorsed the project, saying, “The museum will be an ally of education against ignorance, a fortress of solidarity and civic patriotism in the face of intolerance, antisemitism and discrimination.”

Meanwhile, 600 students — 40% of them non-Jews — are learning about the Holocaust and Israel at the prestigious Laude-Reut Educational Complex founded in 1997 by Jewish philanthropist Ronald Lauder. The private school’s Israeli-born founder and principal, Tova Ben-Nun Cherbis, said classes run from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., and that tuition runs €12,000 per year.

“We have 200 staffers including 11 Hebrew teachers, and everybody studies Hebrew,” said Cherbis, who has lived in Romania for the past 30 years.” Whoever comes here knows it’s a Jewish school, and that it’s considered a bridge between Romania and Israel.”

Jewish and non-Jewish students participate in a mock United Nations debate at Bucharest’s prestigious Laude-Reut Educational Complex. (Larry Luxner)

During the presidential campaign, said Cherbis, a number of teachers privately approached her, warning that if Simion won, they’d consider leaving Romania.

“The people that surrounded him were not prepared to be leaders. They are violent,” she said. “Simion wanted to visit our school twice, but we politely turned him down.”

David Solomonovich, a senior at Laude-Reut, said he’s been called names “multiple times” since the war in Gaza began nearly two years ago, causing him to cut ties with classmates he thought were his friends. Some Muslim youth in his neighborhood have even threatened to stab him, he said.

“Before Oct. 7, I used to wear a Star of David necklace. Now I’m more cautious,” said Solomonovich, 18. He said many of his classmates seemed to think all Israelis are murderers: “If you ask them why, they’ll say they saw it on Instagram or maybe on TV.”

His non-Jewish classmate Sofia Bordei, 17, agreed.

“The vast majority of my generation is against Israel,” she said. “All I see on the internet from people my age are social media platforms promoting antisemitism. And these kids are very easily convinced, because these sites spread misinformation.”

Antisemitism or not, in recent years Bucharest’s Choral Temple — with its imposing Moorish-style architecture and elaborate façade — has become a top attraction for both locals as well as foreign tourists, despite the strict security now required to get past the front gate.

“I have people coming from Iran and the Gulf,” Șaim said. “Muslims are interested in our history and heritage — sometimes, I’m ashamed to say this, more than many of my Israeli visitors.”

Israelis comprise the second-largest source of tourism to Romania after Germans. This is mainly thanks to Israel’s large Romanian Jewish diaspora community and the fact that Romania is a relatively inexpensive travel destination less than three hours by plane from Tel Aviv.

An interior view of Bucharest’s Choral Temple, the largest synagogue in Romania, as seen in April 2024.(Photo by Soeren Stache/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Asked if there’s hope for Jewish life in Romania, Șaim answered with a resounding yes.

He estimates that maybe 20 of Romania’s 80-odd synagogues still conduct services. A few may even offer a daily minyan — perhaps in the cities of Brașov and Oradea — but the Choral Temple is by far the most active synagogue in Romania. Its Shabbat services attract 30 to 40 people; between 200 to 300 come for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

“I have no doubt that, for the foreseeable future, there will be a small number of local Jews here, and an increasing number of Israelis,” he said. “God knows how many, but this is our future.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.