It’s not easy getting teens to think about God. Even if they go to Jewish day school.

When one Jewish educational organization asked day school students in middle school and high school several years ago to respond to the question, “What percentage of your time in Judaic studies do you spend talking explicitly about God?”, some 80% of survey respondents put the figure at less than 10%.

“We don’t have time,” explained one 10th-grader from a Modern Orthodox high school. “We’re too busy studying Talmud.”

“That’s an oy vey,” said Sharon Freundel, managing director of the Jewish Education Innovation Challenge (JEIC), which conducted the survey in 2017. Her organization has been working for several years in small and mid-sized communities to help Jewish educators bring God into the classroom in a systemized and organized way.

This spring the organization – which was founded in 2012 by the Maryland-based Mayberg Foundation to improve Jewish day school education through innovation, experimentation and collaboration – held an Innovators’ Retreat in Seattle.

“The aim is to help kids develop their own relationship with God, or whatever they deem God to be,” Freundel said.

“Kids and adults alike today are thirsting for a spiritual connection to something larger than themselves,” Freundel said. “Whether you call this nature, or global community, or universe, or — as we do — God, we want to help schools and teachers facilitate this relationship formation for each of their students.”

The idea is that connecting to God will assist children in their Jewish identity formation and help ensure they’re more committed lifelong Jews, according to JEIC.

Over the past few years, some 200 schools have received some form of support from JEIC, in part to facilitate God-centered learning — from Reform schools to nondenominational ones to Orthodox yeshivas.

God-centered learning can take myriad forms: pairing off students for discussions, using technology to get kids to think, asking students to meditate or sit in nature, having students listen to music or create art. What’s important, educators say, is to create a lesson plan whose goal is to get students to think about and talk about what God means — or doesn’t mean — to them.

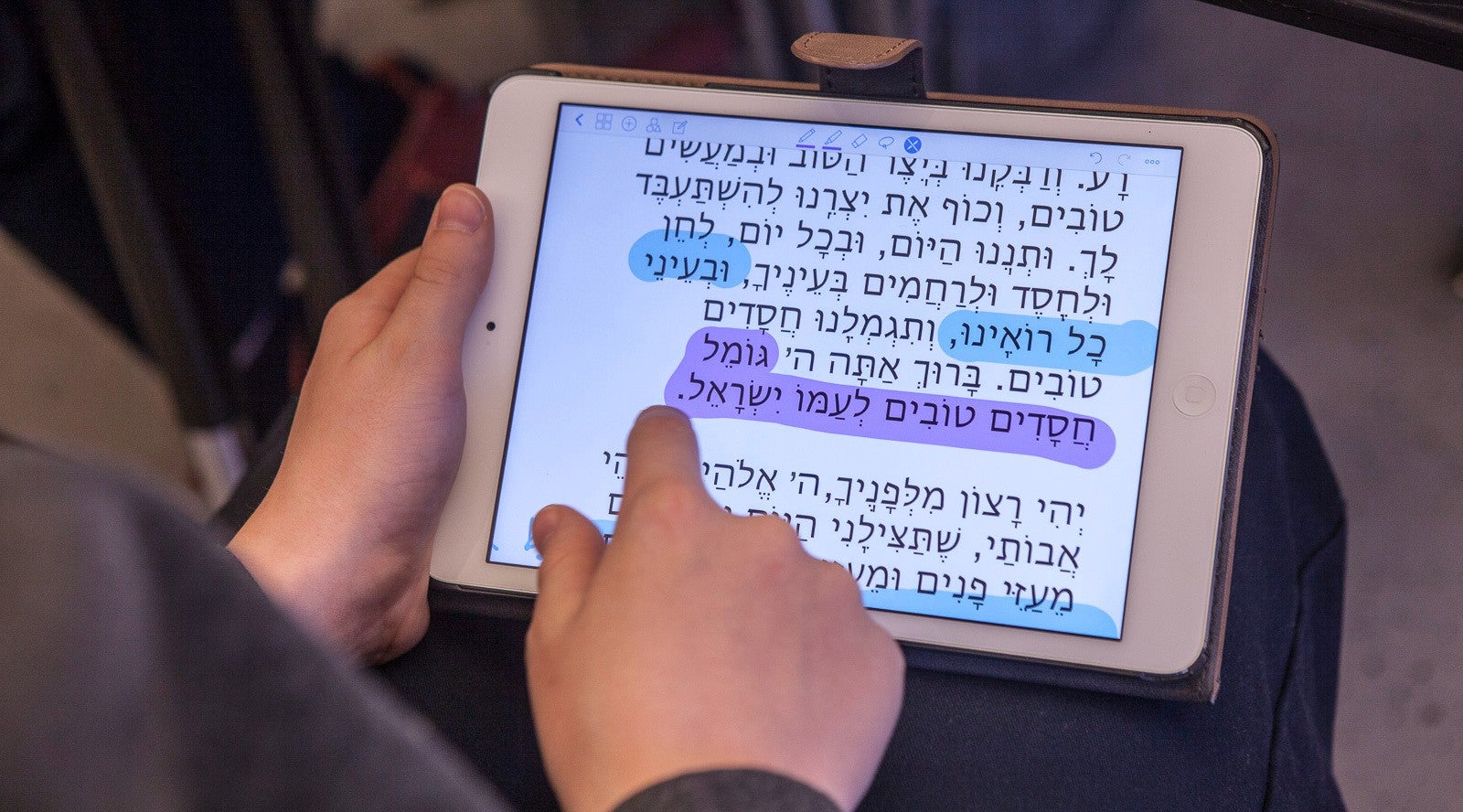

In New York, JEIC worked with the Manhattan Day School to create a program that uses a digital prayerbook app to help students make Jewish prayer more personal. In the program, called Tefillah ReImagined and created with support from JEIC, students are encouraged to highlight passages, write questions in the margins, or even add pictures or doodles. Then, in weekly meetings with a prayer adviser, the students discuss what they added to their prayerbooks and how to make routine prayer more meaningful.

Chaya Elishevitz, head of school for the Chabad MMSC Day School & Seattle Jewish Montessori, said God-centered learning at her schools begins among the youngest students.

Preschoolers are taught “how lucky we are that we have God in our lives, that He’s there for us, protecting us,” and as students get older they learn that “a relationship with God is not simple,” Elishevitz said. “There’s a lot of room for questions.”

At B’nai Shalom in Greensboro, North Carolina, Rabbi Rebecca Ben-Gideon and Eliana Light piloted and developed a program with the help of the Jewish Education Innovation Challenge in which middle schoolers focus on names — both their own and the many names used for God.

In Tefillah Reimagined, students from Manhattan Jewish Day School use a digital prayerbook annotation app to make Jewish prayer more personal. (Courtesy of JEIC)

First, students complete worksheets about themselves, including their given names, whom they’re named for, nicknames, character traits they’re known by, traits they’d like to have and “special names that people call you,” said Ben-Gideon, now an educational coach.

The point is that “your name’s not the same as who you are; it captures part of who you are,” Ben-Gideon said. “The same is true about God. God has many names, but God’s names are not the same as God.”

She notes that the Kaddish prayer uses the word “l’eyla” — “beyondness” — for God: “Just like love, which we can feel but find hard to put into words, our understanding of God goes beyond what we can put into words,” she said.

Rabbi Yehuda Chanales, director of the Lifnai Vlifnim, a Jewish organization that supports schools in developing spiritual growth, worked with the Jewish Education Innovation Challenge on ways to encourage youngsters to develop a relationship with God through active listening. He recommends pairing off students and having one tell about an experience or a story while the other simply listens.

“Someone is listening to you. You’re learning how to talk and feel heard without someone saying anything,” he said. “Then, take it up a level and say: Now, let’s talk to God.”

OpenDor Media’s Unpacked for Educators series, which provides teachers with tools to make Jewish spiritual learning accessible and substantive, created 10 videos with JEIC’s support focused on various Jewish aspects of spirituality, including God, the afterlife, prayer, and why Judaism has so many rules. Alex Harris, senior educator for the program, suggests asking students to try “hitbodedut” — the practice of solitary personal meditation and prayer pioneered by the late 18th century sage Rebbe Nachman of Breslov.

“Go outside, ask them to go into a quiet place, sit, walk around, think and talk to God,” Harris said. “Having a conversation with God is the idea, not to have anything scripted.”

Children should talk about what they’re seeking, what they’re thinking about in their lives, what their worries are, he said.

“Everyone, including young students, has a capacity to have these really deep, important conversations — whether it’s about prayer, whether it’s about free will, whether it’s about God, about Shabbat, but oftentimes they don’t have the language to do so,” Harris said.

The aim of the exercise is to give them the tools for what he called “a lifelong process.”

When over 90 Jewish educators, leaders and funders from around the country came to the Jewish Education Innovation Challenge’s recent retreat in Seattle, which was co-sponsored by the Seattle-based Samis Foundation, they focused in large part on discussing how to implement God-centered learning in their schools. A 2026 retreat is scheduled for Atlanta.

“It’s going to look different in every single school,” Freundel said. “If God is infinite, as we believe, then God-centered learning can have an infinite number of manifestations.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

This article was sponsored by and produced in partnership with the Jewish Education Innovation Challenge, a bold initiative to radically improve the quality of Jewish education in day schools across North America. This article was produced by JTA’s native content team.

More from Jewish Education Innovation Challenge