For the first time in decades, a long forgotten major league baseball player has been posthumously identified as Jewish.

Monte Pfeiffer, who played a single game for the Philadelphia Athletics some 112 years ago, had vanished into baseball obscurity — until a sharp-eyed Yankees fan uncovered a surprising truth written in Hebrew. The discovery, rooted in dusty box scores, old newspaper articles and genealogical detective work, adds Pfeiffer to the rarest of rosters: Jewish major leaguers.

“It’s really like fishing: You throw out your line, and nothing, nothing, nothing,” said Zak Kranc, a 27-year-old lawyer from Connecticut. “Then when you get a hit, you start reeling.”

Such finds are rare. Only about 200 of the more than 23,000 men to play major league baseball since 1871 have been conclusively identified as Jews. It’s a surprisingly tiny fraternity, given the outsized number of honors they have earned over the years, including Rookie of the Year, Most Valuable Player, Cy Young Award and Gold Glove.

Journalist and author David Spaner did most of the detective work in the 1990s. He spent a year sifting through records at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, phoning players and their relatives, and assembling family trees, all in an effort to find unknown Jews. The Vancouver native went on to reveal dozens of newly discovered Jews in “Total Baseball,” a scholarly series edited in part by a baseball historian born to Holocaust survivors.

“There was a form the Hall of Fame sent to family members of the deceased,” Spaner said in an interview. “One of the questions concerned nationality, and a number of players put ‘Jewish’ on it.” He also scrutinized players of unknown heritage who had Jewish-sounding names, and that too yielded discoveries. But Pfeiffer, a German name often associated with Jews, somehow escaped detection.

Thanks to Kranc (pronounced “Krantz”), Pfeiffer is unknown no more.

Montefiore “Monte” Pfeiffer, also known as Moshe Ben Shmuel Yosef, was born in New York City in 1890 to Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe: Fanny Pfeiffer and husband Samuel, a seller of women’s hats. He began playing baseball for money in 1911, at age 19, for the Haverhill (Massachusetts) Hustlers.

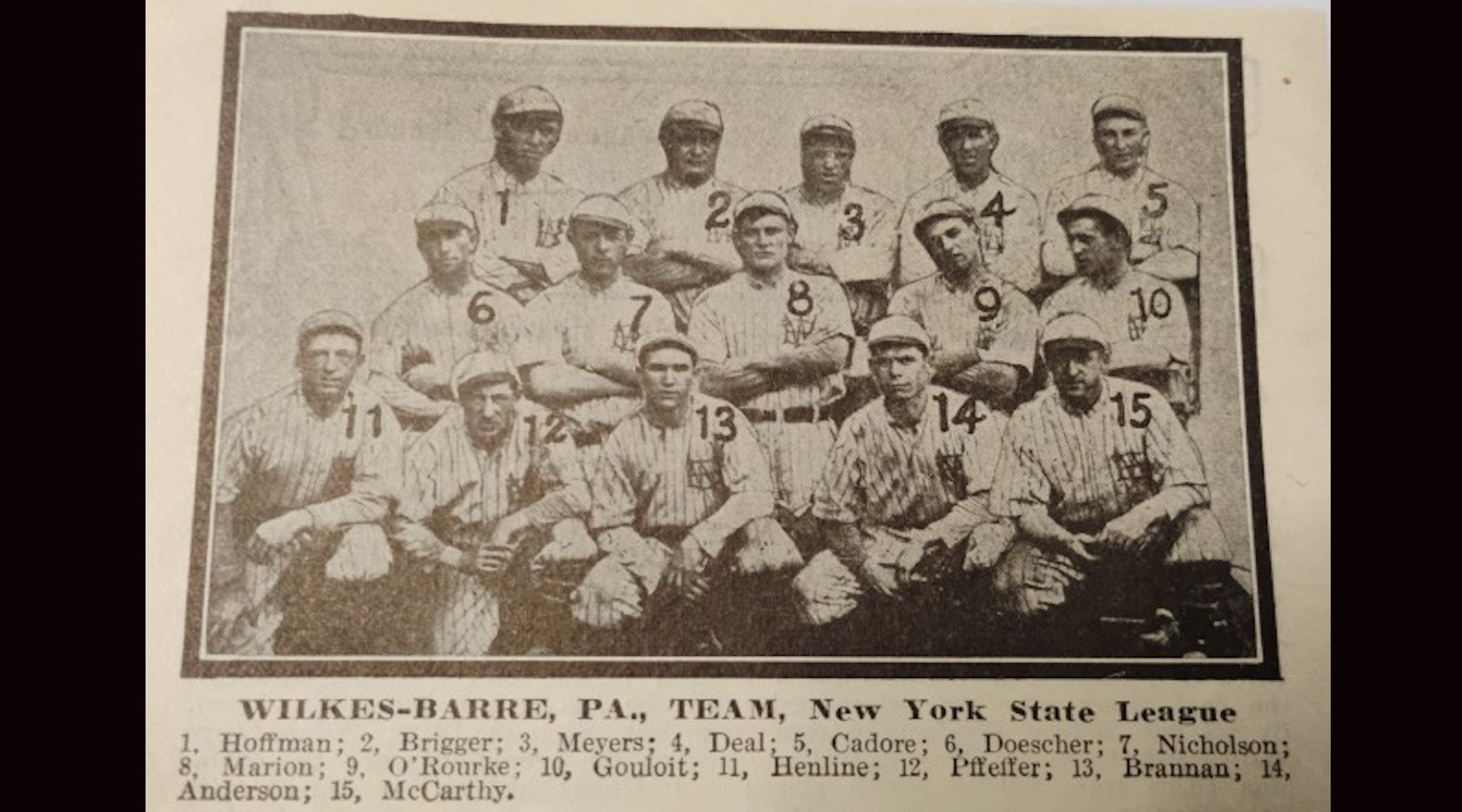

Statistically speaking, Pfeiffer was a middling hitter and error-prone fielder. But he thrilled fans with his speed and jaw-dropping plays. Reporters, too, were dazzled by his exploits, comparing the 5-foot-4-inch infielder to legends like future Hall of Fame inductee Honus Wagner. The Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record called Pfeiffer a “sawed off giant” who carried “a lot of hitting power in his broad shoulders,” according to writer Darren Gibson.

The 1913 season saw breakthroughs for Pfeiffer, as well as a breakdown. Playing for Joe McCarthy, the Wilkes-Barre Coal Barons manager who later led the New York Yankees to seven World Series titles, Pfeiffer attracted major-league scouts — but not before vowing to quit baseball and return to his Bronx pool hall over an alleged antisemitic incident.

According to contemporary news reports, a teammate allegedly told a young woman Pfeiffer fancied that the player was “a Jew and a tightwad who never spent a nickel” — an insult that enraged the shortstop and nearly drove him to quit baseball. Despite McCarthy initially claiming to be “through with ball players that fall in love,” he convinced Pfeiffer to return.

Lucky for Pfeiffer. He wasn’t back on the diamond for long before Connie Mack, legendary manager of the Philadelphia Athletics, chose to rest his “$100,000 infield” for the 1913 World Series and yank three young men, including Pfeiffer, out of regional obscurity to temporarily replace them. The Philadelphia Inquirer cheekily dubbed the trio the “Kindergarten Brood.”

Pfeiffer made his debut in enemy territory: Griffith Stadium, home of the Washington Senators. An estimated 15,000 fans, far above the team’s 4,000 average, would crowd the stands on Sept. 29, 1913 to celebrate George McBride Day, in honor of the Senators’ team captain and shortstop. U.S. Vice President Thomas Marshall would make an on-field presentation.

Observers predicted the three rookies would hit nothing but air against fearsome pitcher Walter Johnson, who arrived that day with a 35-7 record and an ERA hovering just above 1.00. Even Detroit Tigers legend Ty Cobb — a cutthroat Hall of Fame centerfielder who ended the major-league career of another Jewish ballplayer, Jesse “Tiny” Baker, by brutally spiking him with his cleats — was terrified the first time he faced Johnson. “Something went past me that made me flinch,” he said, according to Ken Burns’ documentary “Baseball.” “The thing just hissed with danger.”

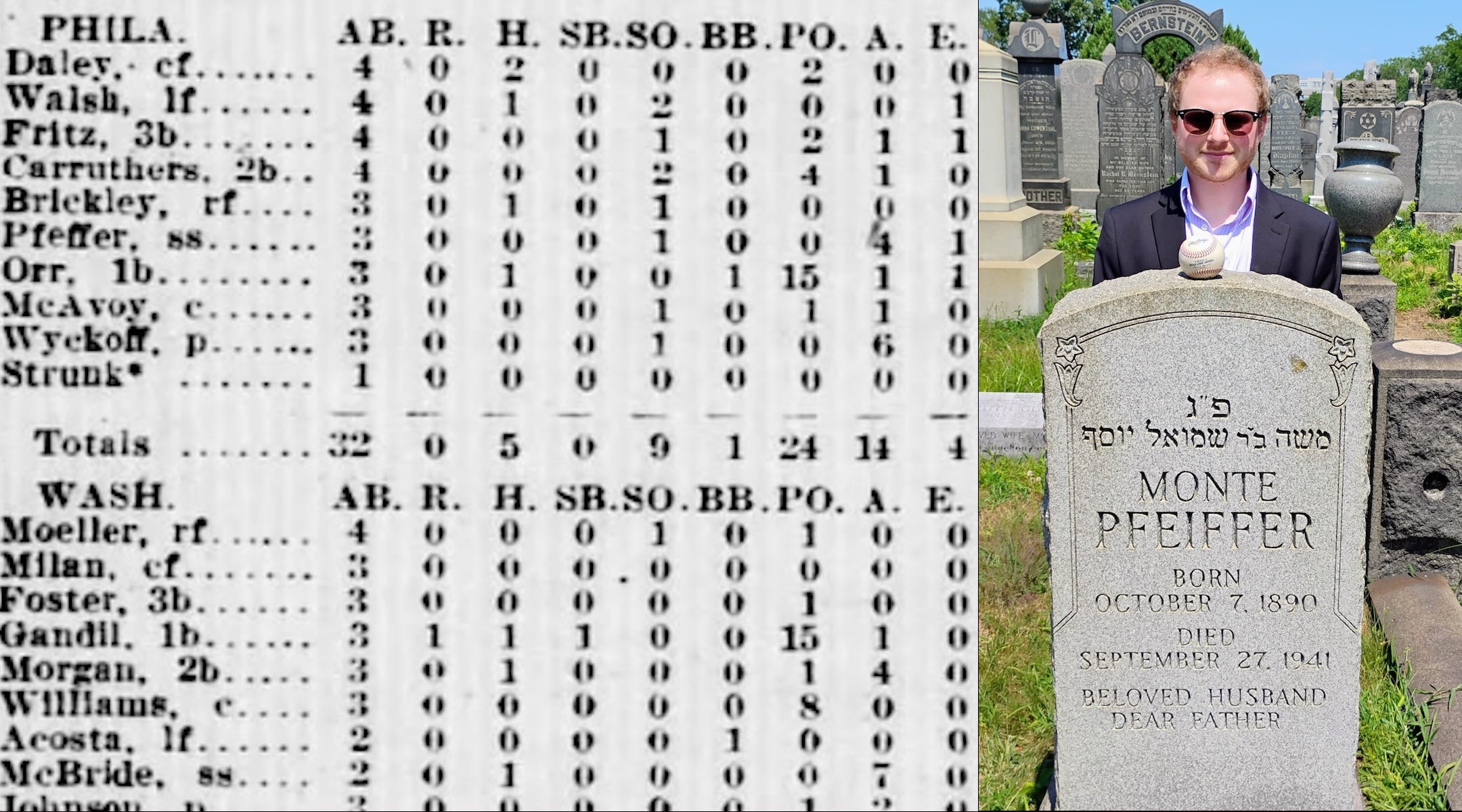

The box score of Monte Pfeiffer’s lone Major League ball game. At right, Zak Kranc poses at Pfeiffer’s grave in Acacia Cemetery, a Jewish cemetery in Queens, New York. (Courtesy Kranc)

Although the Senators wound up blanking Philadelphia 1-0, Pfeiffer never buckled, even after Johnson grazed his sleeve with a pitch. The Washington Times Herald said the 23-year-old “played a smashing good game at short” despite flubbing a grounder. The Washington Post said the “stocky little shortfielder…made several sensational stops” and was “robbed” of a sure hit off Johnson in the 6th inning.

Gibson, who has profiled more than 60 one-game players for the Society of American Baseball Research, sees Pfeiffer as a hard-luck case. “I found it wildly unfortunate that in his one major-league game, Pfeiffer had to square off against Johnson,” he said in an email.

The story of how Kranc discovered Pfeiffer is remarkable in its own right.

The antitrust attorney’s first exposure to Jewish ballplayers came at his bar mitzvah, when he received a framed collection of baseball cards. “It was just a cool thing,” he said. “And I kind of put it to the side.”

Years later, when COVID hit, Kranc thought about the collection. “Everyone was hunkered down and just looking for something to do, looking for an escape from all of the isolation and difficulties,” he said. “And I was like, hey, you know, I like being Jewish. I love baseball, right? I’m going to take this up a level.” He began to hunt for more Jewish baseball cards and autographs — and to search for an undiscovered player.

Several months ago, Kranc was casually scrolling through the website Baseball Reference when he spied a feature called “Cup of Coffee Players”— a nod to those whose big-league careers lasted just one game. Paging through the bios of hundreds of men, he stumbled upon a player listed as “Monte Pfeffer” who had been buried in Acacia Cemetery, a Jewish cemetery in Queens. A few clicks of the mouse took him to Find a Grave, where he located a tombstone he surmised was Pfeiffer’s.

“I saw the Hebrew writing, and I said to myself, ‘Okay, I think we have something here,'” Kranc recalled. He continues to be awed by his unlikely discovery. “I would venture to say the odds of this particular event happening are lower than a perfect game, a triple play, or almost anything else we might find on the field.”

Like Spaner and others before him, Kranc took a disciplined approach to confirming Pfeiffer’s Jewishness. He gathered photos, inspected family trees, read obituaries, and hunted down cemetery records. He also found a descendant, the Honorable Louis “Lou” Meisinger.

A newspaper article about Monte Pfeiffer’s lone major league baseball game as it appeared on Sept. 14, 1913. The Washington Senators honored their captain, George McBride, shown shaking hands with Vice President Thomas Marshall. (Courtesy Zak Kranc)

Meisinger, a retired California judge and entertainment lawyer, never met his great-uncle Monte Pfeiffer, but they shared an important connection: Meisinger’s late mother, Eleanor, was raised with Pfeiffer’s daughter, Frances. Meisinger also briefly owned Pfeiffer’s mitt, though he didn’t understand its significance at the time. “My mother gave me the glove, which she said was given to her by her Uncle Izzy, presumably Monte’s brother,” he said in an interview. “I used the glove in Little League and, unfortunately, discarded it when I graduated to better equipment. It was not in good shape.”

Like many other Jewish sports fans, Meisinger enjoys reading about Jewish athletes. But “there was no family lore about [Pfeiffer], other than that he once played in the major leagues. Nobody provided any details.”

Alas, Pfeiffer’s major league tenure was as scant as the details. When the Athletics returned to Griffith Stadium a day after losing to Johnson’s Nationals, Pfeiffer’s two cohorts were in the lineup, but he had been cut loose. The Wilkes-Barre Record reported that the rookie was “struck on the head by a batted ball and rendered unconscious.”

Pfeiffer’s career swiftly nosedived. In true journeyman fashion, he began the 1914 season with the Kansas City (Missouri) Blues of the American Association, traveled north to join the Marinette-Menominee (Wisconsin) Twins of the Wisconsin-Illinois League, and signed with the Topeka (Kansas) Jayhawks of the Western League. The following year, in 1915, Pfeiffer wrapped up his baseball sojourn in Manitoba, Canada with the St. Boniface Bonnies of the Northern League. His best batting average over the two seasons was a dismal .176.

Pfeiffer also suffered misfortune at home. Things briefly had looked up in late 1914 when he married 18-year-old Rose Schechter, a Jewish native of New York City who soon became pregnant. But two weeks after giving birth to their daughter, Schechter died. Pfeiffer, presumably bereft and unprepared to raise the infant, asked his older sister Mamie to do so. He went on to work as a signal or subway repairman — public records are unclear — and briefly enlist in the military during World War I. As far as we know, the widower never remarried. He was just 49 years old when he died of heart disease in 1941.

Today, Monte Pfeiffer’s great-great-grandnephew Aric Berg pitches for Fordham University — a reminder that, more than a century after his lone appearance, Pfeiffer’s story is still being written.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.