Returning to Chicago from an artist residency in Maine, Gabriel Chalfin-Piney-González surveyed the local Jewish museum scene and found it wanting.

“When I came back to Chicago, I wanted to get involved with the ‘Jewish Museum of Chicago,’ and, you know, lo and behold, it doesn’t exist,” said Chalfin-Piney-González, who uses they/them pronouns. “I found that kind of strange.”

So Chalfin-Piney-González set about creating the museum they dreamed of — a cultural center without walls that would offer a hub for Jewish artists in Chicago to connect and showcase their work.

The Jewish Museum was founded during Passover in 2023 and described itself in its first Instagram post that August as a “community-run museum crafting accessible multi-faith and multigenerational entry points to diasporic storytelling, organizing, and cultural art practices.”

It has also found an additional motivation — to create a community space for anti-Zionist Jews in Chicago who have been galvanized during the war in Gaza but feel that the city’s Jewish institutions are not welcoming to them.

“A lot of the people I know who are interested and involved in this community are people who are trying to find meaning outside of any sort of state, any sort of government,” said Chalfin-Piney-González. “I left Judaism for a long time because I didn’t see any of their options, and I think that this community is surfacing because it needs to.”

Two years later, the museum has hosted over a dozen exhibitions and Jewish community events, beginning with its founding “Liberation Seder” in 2023 and continuing through the recent announcement of an artists collective that drew dozens of applications.

The Jewish Museum of Chicago presents Chicago Artists for Palestine Exhibition + Fundraiser, organized in partnership with ACRE from May 18 to June 2, 2024. (Brittany Sowacke)

So far, the initiative hasn’t taken firm steps toward its ultimate goal of having a brick-and-mortar space in Chicago. But it has gained attention from both Jewish and non-Jewish artists in the city — and from Jewish critics who believe anti-Zionism is a rejection of a key component of contemporary Jewish identity and a repudiation of the safety and security of the 7 million Jews who live in Israel.

Sarah Zarrow, a professor of Jewish history at Western Washington University, said the Jewish Museum of Chicago stands out against other contemporary Jewish museums like the Jewish Museum in New York.

“This is a Jewish museum that will be out of step with the Jewish mainstream,” said Zarrow, who has studied Jewish museums. “So in that regard, this museum seems totally new, that it will just be an absolute minority, presenting a minority view within the Jewish community.”

Indeed, Jay Tcath, the executive vice president of Jewish United Fund, Chicago’s Jewish federation, said the new project was “not representative of a significant swath of the American or Chicago Jewish community.”

Despite the pushback, the initiative has borne out the ambitions of Jewish anti-Zionists who say there is a need to add distinctively Jewish content to the coalition building they have done since the start of the war in Gaza.

“It was really a special experience to work with the Jewish Museum of Chicago because they’re really cultivating a different generation and a different community of Jewish people who normally don’t have as much of a grounding presence within the art world,” said Grace Gittelman, a ceramicist who showed an exhibition titled “The Dybbuk in the Mirror” with the museum last fall.

“If we mean to fight the weaponization of our identities, we will have to create a version of them we can fully inhabit,” Arielle Angel, the editor of Jewish Currents, wrote in a recent essay calling for new institutions for anti-Zionist Jews. “If we hope to weaken Zionism within Jewish communities, we will need to develop a substantial vision for contemporary Judaism; we will need to meet those who want an exit from the rot with something beautiful and real. We cannot ask them to jump and decline to catch them.”

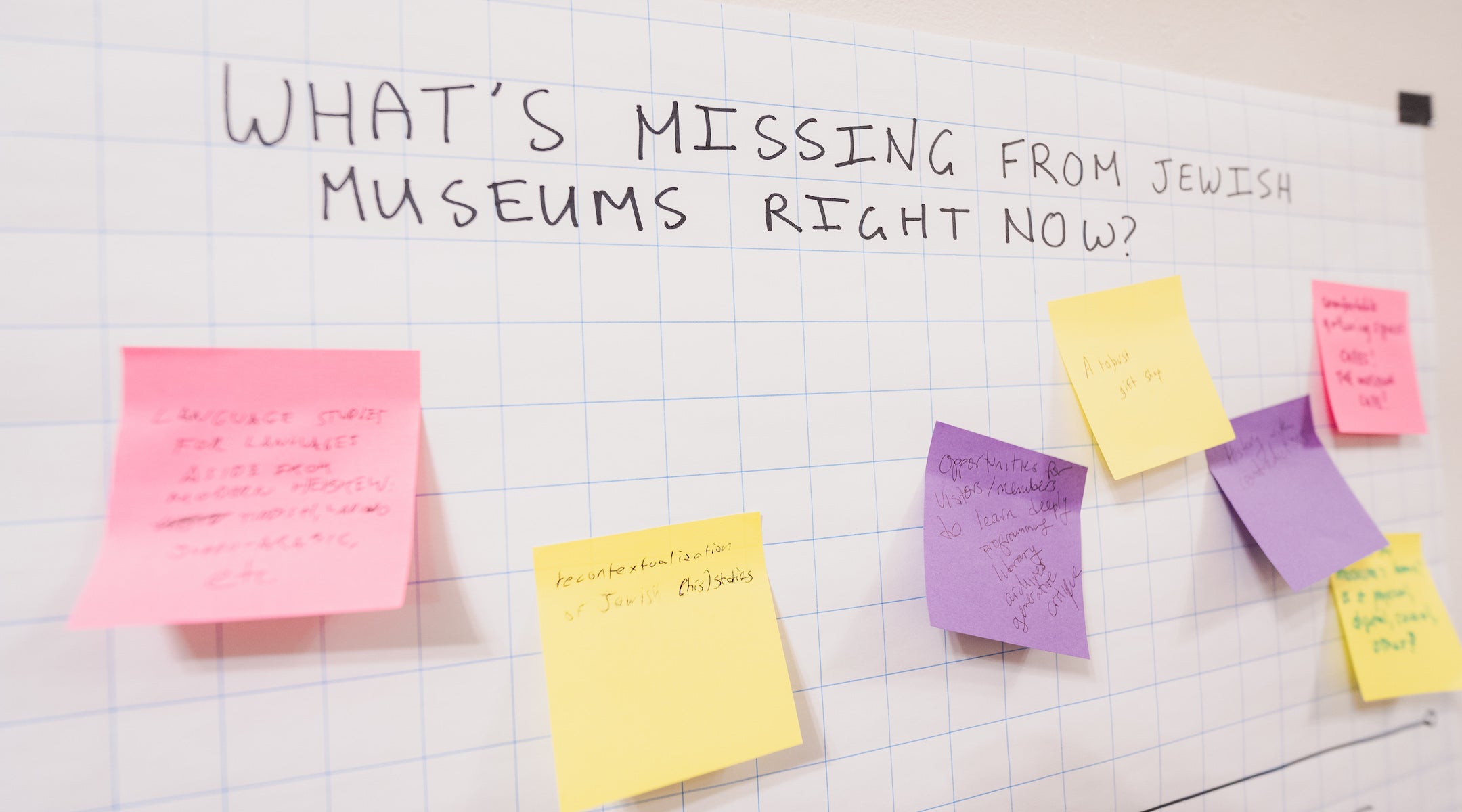

Attendees at Comfort Station in Chicago worked together with the leaders of the Jewish Museum of Chicago to brainstorm the Museum’s ideological and practical framework on Dec. 13, 2023. (Ricardo E. Adame)

Chalfin-Piney-González has a foundation to build on in Chicago. The city is home to the first anti-Zionist synagogue in the United States, Tzedek Chicago, with which it collaborated for a Purim event this year.

Brant Rosen, Tzedek Chicago’s rabbi, praised the museum as part of a “growing ecosystem in Chicago of anti-Zionist projects,” including the Chicago chapter of the pro-Palestinian activist group Jewish Voice for Peace, the traditional egalitarian minyan Higaleh Na and the Klezmer band Upshtat Zingerai.

“What we share is these common values of looking at Judaism from a Diaspora point of view, rejecting Jewish nation-statism as the primary lens for understanding what it means to be Jewish collectively,” Rosen said, adding, “They’re doing it from the lens of artistic expression, and we’re doing it in the lens of spiritual expression, and I think there’s a lot of overlap.”

Rosen said that Tcath’s characterization of the Jewish anti-Zionist community in Chicago as representative of a tiny minority was “problematic,” adding that “many Jews, and particularly young Jews, are disaffiliating from identification with Zionism and with Federation-style Judaism.” Tzedek Chicago has added around 100 new families since Oct. 7, 2023, Rosen said.

“If organizations like the Jewish Federation and other Jewish institutions that are pro-Israel and Zionist represent the Jewish people, then, God help us,” said Rosen. “We are small and we are modest, but we are growing, and we are ready to receive the numbers of Jews who will undoubtedly peel away from a Judaism of oppression and genocide, and will be happy to build a new Judaism.”

Tcath said that JUF would not be promoting, endorsing or funding the museum’s activities, adding that he believed their involvement would be at odds with the museum’s mission.

“From what I’ve read from their worldview, they should feel sullied were they to seek out our hekscher [kosher endorsement] or our money because we, in their worldview, are part of the complicit American Jewish establishment, complicit in the misrepresentation of the Holocaust, what the Holocaust means to Jewish life in the alleged oppression of the Palestinians,” said Tcath.

Chalfin-Piney-González grew up going to Temple Beth-El, a Conservative congregation in Poughkeepsie, New York, where they attended Hebrew school and celebrated their bar mitzvah.

A fissure came when they were 14 and began taking a Wednesday night class about “conflict in the Middle East,” Chalfin-Piney-González said. When they asked a question about the Palestinian perspective, it did not go over well.

“I was reprimanded in front of the class, and then asked to not continue coming to that class, so I stopped going to the school altogether,” said Chalfin-Piney-González.

It wasn’t until around 2020 that Chalfin-Piney-González reconnected with Judaism, and not until the following year that they began to encounter a way of engaging with tradition that felt like a clear fit. That year, Chalfin-Piney-González moved to Maine to establish an artist residency at the Colby College Museum of Art. There they discovered the Maine Jewish Museum, which hosts rotating contemporary Jewish art exhibits.

During their time in Maine, the Jewish museum hosted several artist talks, a virtual art auction, a cyanotype printing workshop and exhibitions.

When they returned home in 2022, they looked for that kind of community locally — and came up short.

The Spertus Institute, a longstanding center for Jewish education in Chicago, offers an academic approach to Jewish culture and history, with scholarly programming and a vast closed-stacks and remote-access library — but not much in the way of arts or community activities.

The Chicago suburb of Skokie is home to the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, which doesn’t focus on Jewish art and, Chalfin-Piney-González said, runs counter to what many Jewish artists aim to showcase in their work.

“A contemporary Jewish art museum and the Holocaust being synonymous with each other, to me, is not fair to Jewish art at large,” they said. “We want to tell stories that are not just about strife and suffering, but are also about joy and longevity and not based around fear.”

Tcath pushed back on the museum’s comparison to the Skokie Holocaust Museum, which he described as “unfair and wrong.”

“It’s unfortunate, but also telling, that they feel compelled to define themselves in critical contrast to the vast majority of the Chicago Jewish community, whether it be the Zionism of that community, the understanding of the importance of Israel and the Shoah to our community, and the misrepresentation of our wanting to learn and educate about the Holocaust as being some type of white, privileged Ashkenazi-motivated impulse,” said Tcath.

In the Jewish Museum of Chicago’s first social media post after Oct. 7, Chalfin-Piney-González wrote that they hoped the platform would offer those interested in anti-Zionism “space to grieve, tangible forms of solidarity and care, organizing and art opportunities,”

Last year, the group hosted a series of art auctions from dozens of Chicago artists and donated the proceeds to Palestinian families, according to Chalfin-Piney-González. It also partnered with Pushcart Judaica, an online shop that sells Jewish art and ritual items, to host a pop-up market, fellowship exhibit, and community workshops.

With the museum’s work unfolding amid Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza, Chalfin-Piney-González said the project has drawn backlash on social media as well as in-person confrontations they described as “very dogmatic and very one-sided.”

“I think it’s emboldened a lot of hate in many directions.” said Chalfin-Piney-González, adding that they had grown exhausted from moderating the amount of “hate mail” coming into the museum.

But for the artists who have already been drawn to the Jewish Museum of Chicago, the endeavor has brought relief.

Gittelman, whose work often explores their upbringing in a Korean-Jewish household, said their exhibition with the museum last fall was the “first time” they were able to present their work primarily as a Jewish artist.

“I feel like it really changed the way that I felt about myself as a Jewish artist,” said Gittelman about the exhibition experience. “I felt really proud to be a part of the Jewish Museum, and I felt like, okay, this is something that I can do and not be so scared of what it would feel like to be the only Asian person in a space.”

Gittelman said that prior to the museum’s founding, they had recognized a lack of a “home base” for Jewish artists in Chicago.

“I saw that Gabriel had started this museum, and I was immediately very excited about it, because of the need that I had already seen within Chicago to create this kind of sense of community within Jewish artists,” said Gittelman.

Grace Gittleman and Eleanor Frick at an exhibition titled “The Dybbuk in the Mirror” with the Jewish Museum of Chicago on Oct. 27, 2024. (Ricardo E. Adame)

Maya Kosover, a multi-media collage artist who is the initiative’s artistic director, said the project is a “supplement” to Chicago’s Jewish ecosystem. For her, the museum’s anti-Zionist underpinnings are only part of the story, and its mission is ultimately about building something broader.

“I imagine it being a really active hub for a lot of this cultural arts building and community building,” said Kosover. “It really has a transformative justice ethos, and it’s really a love-based project for ourselves as Jews and for the communities that we’re in solidarity with.”

To that end, the team is now in the process of forming an artists collective.

While the effort is still in process, Chalfin-Piney-González said that an initial inquiry form collected about 65 applications.

Nearly two years on from the museum’s founding seder, Chalfin-Piney-González said that they hope the project remains “able to change” and “adapt to the needs of the community.”

“We’ve decided to keep the name Jewish Museum of Chicago, but if you look at what we’ve actually been doing, it’s much more of like a community center than anything else,” Chalfin-Piney-González said. “I think that’s really where it’s going,”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.