On stage last Sunday at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the comedian Alex Edelman told a Jewish joke that he said he once read in an academic journal.

It essentially goes like this: A man goes to heaven and meets God. Eager to please, the man asks God if He’d like to hear a joke. “I love jokes,” says God. So the man tells God a Holocaust joke. God doesn’t laugh and says, “I don’t find that funny.” “Well,” says the man. “I guess you had to be there.”

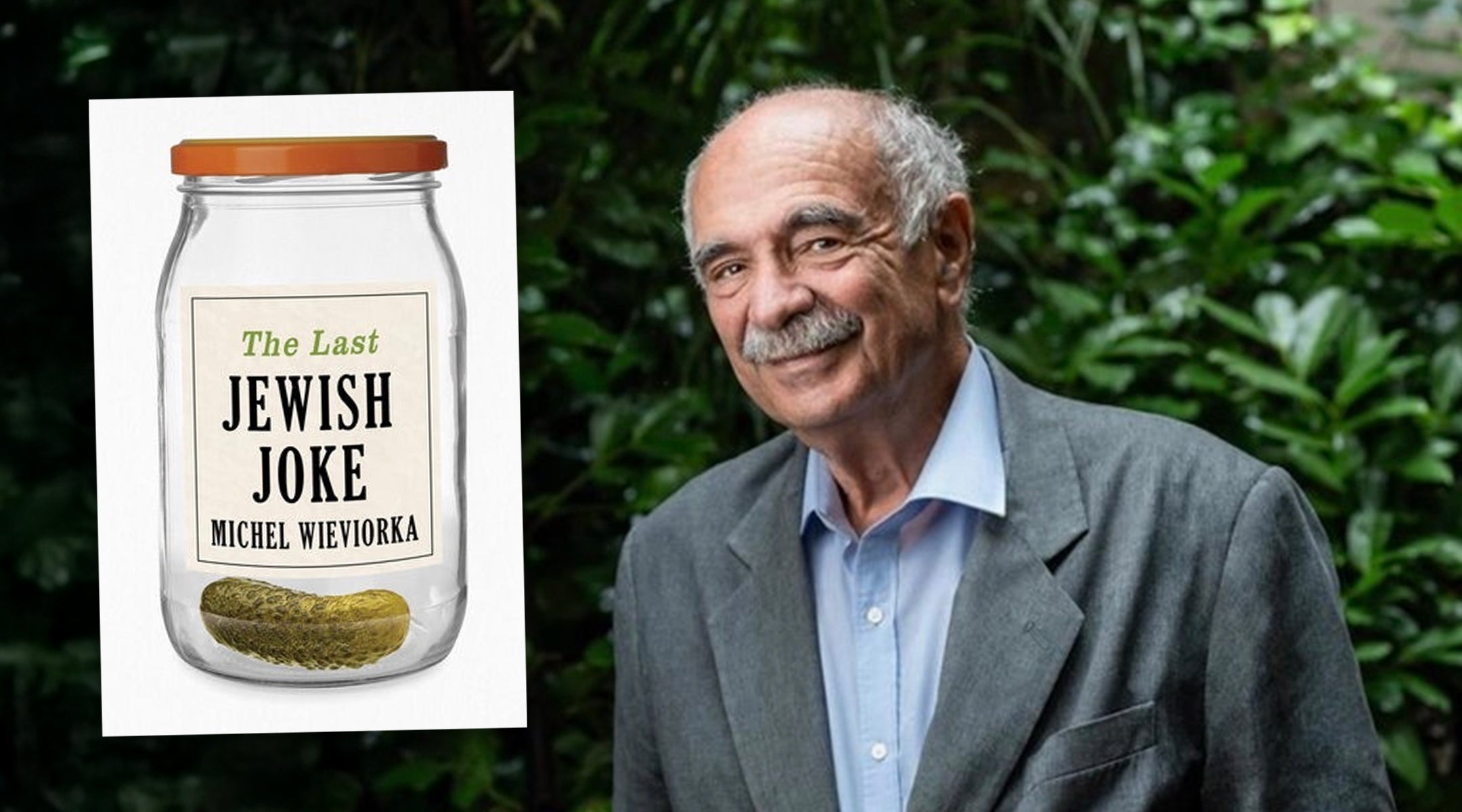

That startling punchline echoed as I read “The Last Jewish Joke,” a new book on the rise and decline of Jewish humor by the eminent French sociologist Michel Wieviorka. The son of Holocaust survivors from Poland who also enjoyed a good Jewish joke, Wieviorka, 79, asserts that after a period of communal security and acceptance that followed the horrors of World War II, the conditions that led to the flourishing of Jewish humor have been depleted, both in the United States and France.

“This book is not a catalog of Jewish jokes,” Wieviorka, professor of sociology at EHESS, Paris, told me in an interview. “It’s really an analysis of a golden age which is past.”

I understand what he means, even if I don’t necessarily agree with his conclusions. From the 1960s to roughly the year 2000, he suggests, American and French Jews enjoyed a period of openness: antisemitism was in decline, both countries moved toward a form of multiculturalism, there was a general consensus that the Holocaust was bad and that Israel was a force for good.

In such an environment, he writes, “Jewish humor had a very clear and visible place, often found in political debates and also in literary, artistic, and intellectual life.”

The past 25 years, however, saw a rise in antisemitism on both the right and the left. Islamists, Holocaust deniers and conspiracy theorists targeted Jews each in their own ways. Openness fasttracked assimilation, and a waning of engaged secular Jewishness. Israel was on its way to becoming an international pariah state, and Jews lost their status as a historically persecuted minority and were promoted to the status of privileged whites.

“The space for benevolent feelings toward Jews became narrower and narrower,” he said. “And when this space is narrower and narrower, it’s more difficult to make humor, not only for your group, but also for people other than those that belong to your group.”

The golden age that he describes — which in the United States roughly extends from the heyday of the Borscht Belt to the finale of “Seinfeld” — encouraged what Wieviorka considers three essential traits of Jewish humor. First, it laughs at ourselves — not at others. Second, it doesn’t punch down: Anti-Belgian jokes may work in Paris cafés, but Jewish humor doesn’t thrive on cruelty. Third, it needs community. You can’t tell a Jewish joke in a vacuum; you need a knowing audience, a minyan of laughter.

The ideal Jewish joke also says something funny about the Jews without giving succor to antisemites. There is an assumption, says Wieviorka, that everyone is in on the joke, Jews and non-Jews alike.

He offers an example, a joke told by a family friend who worked in the shmatte, or clothing, business: A client places a large order at a wholesale clothing store in the shmatte district. When he asks for a receipt, the perplexed clerk consults with his boss. “A receipt?” says the boss, indignantly. “What kind of scam is he trying to pull?”

Wieviorka loves the joke, first of all, because his own forebears worked in the rag trade. While the joke leans into an antisemitic trope — the wily businessman — it does it in a way that a non-Jewish audience would identify with: nobody wanted to pay taxes in postwar France. And he likes the way it is a joke Jews tell on themselves — recognizing the absurdity of the boss’s paranoia, and how his accusation is a confession.

It’s a joke that could be told without reservations from the 1970s to the 1990s, when the Diaspora, he writes, “felt things were going rather well.”

In describing how things ended up going rather poorly, Wieviorka’s analysis seems spot on. “When the genocide and indeed the shock of its discovery lose their primacy as references, when interest in the intellectual heritage and cultural vitality of Yiddishkeit begins to wane, when Israel ceases to be viewed in a positive light, and when the capacity for bringing to life a Jewishness that also interests non-Jews is absent, these jokes can only appear as vestiges from the past,” he writes.

In “The Last Jewish Joke,” Michel Wieviorka argues that the conditions that allowed Jewish jokes to flourish belong another, more welcoming, era. (Polity; Eric Garault)

Except when they don’t, and that’s where I part ways with Wieviorka. Despite his dire warnings, Jewish humor appears alive and well, at least in the United States. The new Netflix animated series, “Long Story Short,” is a satire of a contemporary Jewish family, slathered with Yiddishisms and insider Jewish jokes and references. Another Netflix series, 2024’s “Nobody Wants This,” is about a single rabbi who falls in love with a non-Jewish podcaster. It abounds with jokes about Shabbat, rabbis and, of course, intermarriage, and will return for a second season on Oct. 23.

Edelman, meanwhile, has had uncommon success with his one-man show, “Just for Us,” a stand-up comedy special about his boyhood at a Jewish day school and his more recent attempts to understand the antisemitism of white supremacists. The show moved to Broadway, is available on Netflix and launched Edelman into a higher plane: He’s in the cast of “The Paper” on Peacock. The show is a spinoff of “The Office,” NBC’s wildly popular and influential sitcom.

Even Edelman’s appearance at JTS was confirmation that Jews still love their comics. He shared a stage with the memoirist and novelist Shalom Auslander at “Spoiler,” a three-day festival celebrating the new MFA in Creative Writing program at Conservative Judaism’s flagship university, where both are teaching. The director of the program is the Israeli writer Etgar Keret, whose short-short stories seem to start as jokes — a talking goldfish grants wishes, a man dates a woman who transforms at night into a beer-drinking bro — and end with an emotional punchline.

All of the comic projects above are trying to say something new. Yes, “Long Story Short” propagates the Jewish mother stereotype and “Nobody Wants This” includes cringey “shiksa” jokes and a few unpleasant stereotypes of its own. But both shows mine laughs from specific Jewish folkways in ways even the great Jewish comedians of the ”golden era” would not have dared. The same can be said for the 2020 comedy “Shiva Baby,” Adam Sandler’s 2024 movie “You Are So Not Invited to My Bat Mitzvah,” the 2025 farce “Bad Shabbos” and choice episodes of Larry David’s sitcom “Curb Your Enthusiasm.”

Even the Holocaust joke Edelman told feels fresh. In the guise of a staple of Jewish humor — guy goes to heaven, gets to meet God — it poses the central challenge of post-Shoah theology: “Where was God in the Holocaust?” Try that in the Catskills.

So much of what we call Jewish humor — of the Ashkenazi, American kind, anyway — is based on nostalgia. That’s not a bad thing. Judaism itself is a culture of retelling old stories, in hopes of connecting generations with a common vocabulary. Jewish humor can itself be a form of identity — which is better, as Wieviorka concedes in the conclusion of his book, than a “pure and simple forgetting.”

So maybe the last Jewish joke isn’t the last after all. Maybe it’s just the latest retelling of an old story — ours — one that keeps finding ways to make us laugh when the world conspires to make us cry.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.