THESSALONIKI, Greece — Fronting the Mediterranean Sea in this bustling Greek port stands a haunting monument to the city’s roughly 50,000 Jews who were rounded up by the Nazis in 1943 and deported to Auschwitz. Each year on Holocaust Remembrance Day, local dignitaries and Jewish leaders make speeches and lay wreaths at the monument in their memory.

One of those dignitaries is Akis Dagazian, Armenia’s honorary consul in Thessaloniki (known in Turkish Ottoman times as Salonika). He says the ethnic Armenian presence in this ancient city dates back to the Byzantine era, while the Jewish presence goes back even further, to Roman times. And like the Jews, the Armenians have long dominated commerce and trade, and have excelled in professions such as law and medicine.

Sadly, the Armenians share something else with their Jewish brethren: the collective trauma of a genocide. The Armenian Genocide took place 110 years ago and is still often dismissed as a consequence of the First World War.

“This is the recent official Turkish narrative. At least they admit something happened in 1915,” Dagazian said over breakfast at the waterfront Café Mazu, a few blocks from the Holocaust memorial. “According to Ottoman statistics, before the Balkan wars, more than 2 million Armenians were living in the Ottoman Empire. Now there are only 50,000. I want someone to tell me what happened to the rest of them.”

By most accounts, the Ottoman Turks are believed to have killed about 1.5 million Christian Armenians during World War I. Romania was among the first countries to welcome Armenian refugees after the genocide, but for economic and strategic reasons, Romania has yet to officially recognize that genocide.

Israel only just recognized the genocide, in comments made by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu last month following the collapse of relations with Turkey. (It comes at a time when the world is debating whether Israel is committing a genocide of its own, in Gaza, a charge that Netanyahu rejects.) President Joe Biden was the first U.S. leader to acknowledge the genocide, in a 2021 move that divided Jewish groups.

The first nation that did was Uruguay, in 1965. Greece followed in 1996 and went a step further.

“In 2014, the Greek government criminalized denial of the Armenian genocide under the same law that criminalizes denial of the Holocaust,” Dagazian said. That’s not surprising, given that Armenians have been living among Greeks for centuries, and that Armenians are also mentioned in ancient Greek literature, with ties between the two ethnicities dating back to antiquity.

The Armenian Community Center in Thessaloniki, Greece, is the heart of the 50,000-member local minority. (Larry Luxner)

Dagazian, 50, belongs to the oldest Armenian family in Greece. His forefathers arrived some 300 years ago, settling in Komotini, about 240 kilometers east of Thessaloniki. They were part of the first wave of Armenians — merchants and craftsmen who thrived in the region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, as well as the island of Crete.

The second wave consisted of Armenians fleeing first the genocide, and then the collapse of the Greek front in 1922 in what came to be known as the Asia Minor catastrophe. That brought another 80,000 to 100,000 Armenians to Greece. Yet from the mid-1920s to around 1948, most of these later arrivals returned to Armenia — by then a Soviet republic — while a significant number also emigrated to Europe and the Americas.

The community rebounded in 1991 after the breakup of the USSR, when 40,000 Armenians — the third wave of immigrants — relocated to Greece, most of them settling in Athens.

Yet unlike any other major city in Europe where Armenians wound up en masse, Thessaloniki was the only one with a Jewish majority.

A Jewish family in Thessaloniki in 1917. (Elias Petropoulos/Wikimedia Commons)

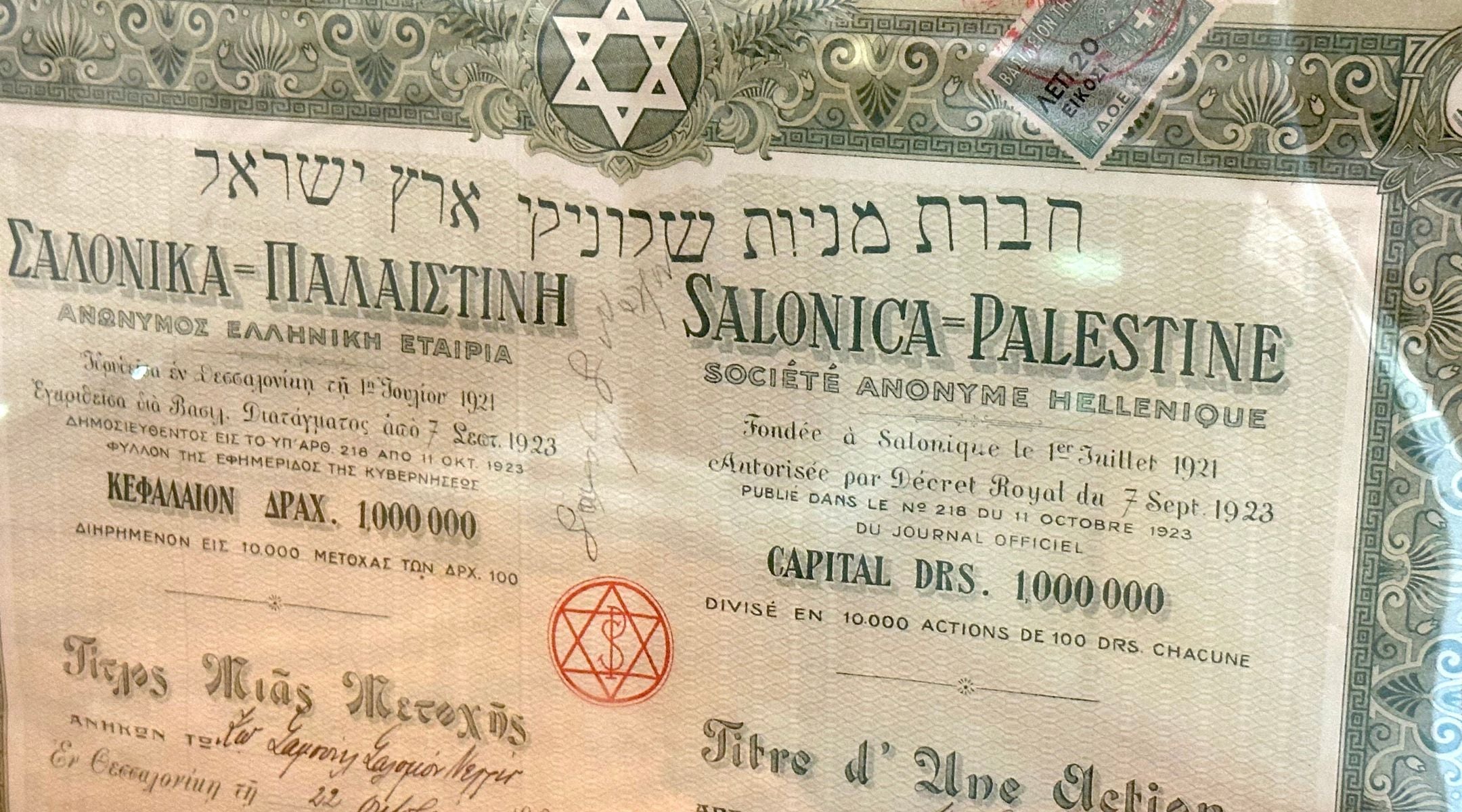

In an 1882-84 census conducted by the Ottoman government, Jews accounted for about 48,000, or 56%, of the city’s 85,000 inhabitants. And in the first census conducted by the Greek government in 1913 — two years before the Armenian genocide — Jews were less than half of the total, yet they remained the largest single group, with 61,439 Jews out of a total population of 157,889. In fact, Thessaloniki had more Jews than either Greek Orthodox Christians or Muslims, and far more than the handful of Armenians who were then living in the city.

By 1919, according to the newspaper L’independent, Jews accounted for 90,000 of the city’s 170,000 residents, or about 53%. None of other 31 Greek towns where Jews lived at that time had more than 2,500 or 3,000 members.

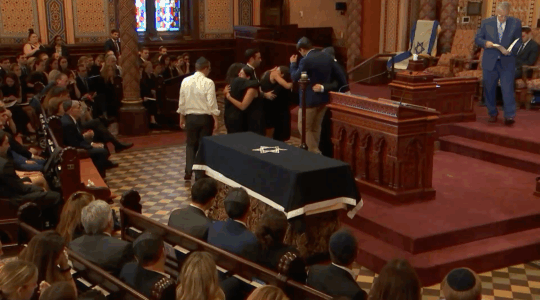

Today, as a consequence of the Holocaust, barely 1,000 Jews live here. Last year, Thessaloniki-born Albert Bourla, CEO of pharmaceutical giant Pfizer and winner of the 2022 Genesis Prize, broke ground on the Holocaust Museum of Greece. The 9,000-square-foot museum, to open in 2026, will occupy eight floors in an octagonal structure at the site of Thessaloniki’s Old Railway Station, where the first Nazi train carrying Jews to Auschwitz departed on March 15, 1943.

Genesis Prize Foundation Chairman Stan Polovets, left, with German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier at the groundbreaking for the Holocaust Museum of Greece in Thessaloniki, Oct. 29, 2024. (Courtesy of Genesis Prize Foundation)

Dagazian, who like many other Greek Armenians is in the jewelry business, can read and write Armenian, though he is not fluent in the language of his ancestors.

What keeps the community together is religion. Armenian cultural life revolves around the Armenian Apostolic Church, an Orthodox denomination that dates from the year 301 C.E., when Armenia became the first country to adopt Christianity as its official religion.

For 120 years, the focal point of community life here has been the Armenian Orthodox Church of the Virgin Mary. It’s located on Dialeti Street less than a mile from the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki, which according to its director, Xenia Eleftheriou, attracted some 30,000 visitors in 2023, triple the 10,000 who came in 2021 at the height of the COVID pandemic.

Inaugurated in 1903, the church — designed by the renowned Italian architect Vitaliano Poselli — is a single-aisle basilica with a vaulted roof, and a three-story bell tower topped by a square pyramid. The church survived the great fire of 1917, which decimated most of the city, including its historic Jewish quarter.

Akis Dagazian, Armenia’s honorary consul in Thessaloniki, stands in front of the Armenian Church of Virgin Mary. (Larry Luxner)

Agkop Kasparian is president of the Armenian Community of Thessaloniki. He said about 5,000 Armenians live in Thessaloniki, of which 1,000 are from the older established group; the rest came after 1991. Among other things, the community supports an Armenian school that offers language and history classes to some 100 students each Saturday.

“Our interest is to preserve our traditions, language and identity, and to support the Armenian state, and to stand strong in the difficult international environment,” he said. “We do this through cultural activities, dance groups, musical events and fundraising.”

Ties to their ancestral homeland are paramount among the Armenians here.

Although he no longer has family in Armenia, Kasparian has been there several times. His first visit was in 1991 — shortly after Armenia’s independence — to accompany a plane carrying 40 tons of aid for families displaced by a catastrophic earthquake three years earlier. He went again in 1993 with Foreign Ministry officials to help acquire the building that now houses the Greek Embassy in Yerevan.

In total, about 50,000 Armenians live in Greece today, according to Dagazian — but he said their cultural distinctiveness was eroding.

“Being a Christian in another Christian country, it’s much easier to assimilate after four or five generations. In the case of Jews, having a different religion is what keeps your community isolated from the others,” he said. “This actually presents a threat, in that right now, the rate of mixed marriages between Greeks and Armenians is 95%, which means that in a few generations, our kids will be hellenized.”

Despite his deep respect for Judaism and admiration for the modern State of Israel, Dagazian is disappointed with the behavior of some haredi Orthodox Jews who have humiliated priests and even spit on them in the Old City of Jerusalem.

“The attitudes of these Jews do not correspond to the values of the Talmud or the Jewish religion,” he said. “They are targeting mostly us simply because we are the only Christians living there. The presence of all the other Christian denominations in the Holy Land consists mostly of just clergy are just priests, but in our case, ethnic Armenians form a solid ethnic majority that has been living there for 1,700 years continuously and uninterruptedly.”

Dagazian noted that in some ways, it was the genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Turks against the Armenians that made the Holocaust possible. He cited a 1939 speech by Adolf Hitler, who justified his plan to exterminate the Jews with the comment: “Who, after all, remembers the annihilation of the Armenians?”

This, he said, is why global recognition of what really happened to his ancestors is so important.

“We feel so close to the Jewish community because we have experienced similar tragedies, and we face similar challenges as well,” he said. “This threat of assimilation is something we both face—not only now, but through the ages, especially the Jews, because they have been 2,000 years away from their motherland, but also the Armenians. Since Byzantine times we have been relocating to other territories. That’s why I believe we are the only ones who can really understand what it means to be a Jew — but more importantly, remain a Jew — in the Diaspora.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.