I last appeared before a judge 40 years ago when I tried fighting an “unjust” speeding ticket. That didn’t go so well. As they say, “He who represents himself has a fool for a client.” My takeaway: pay the fine and don’t add insult to injury by paying court costs.

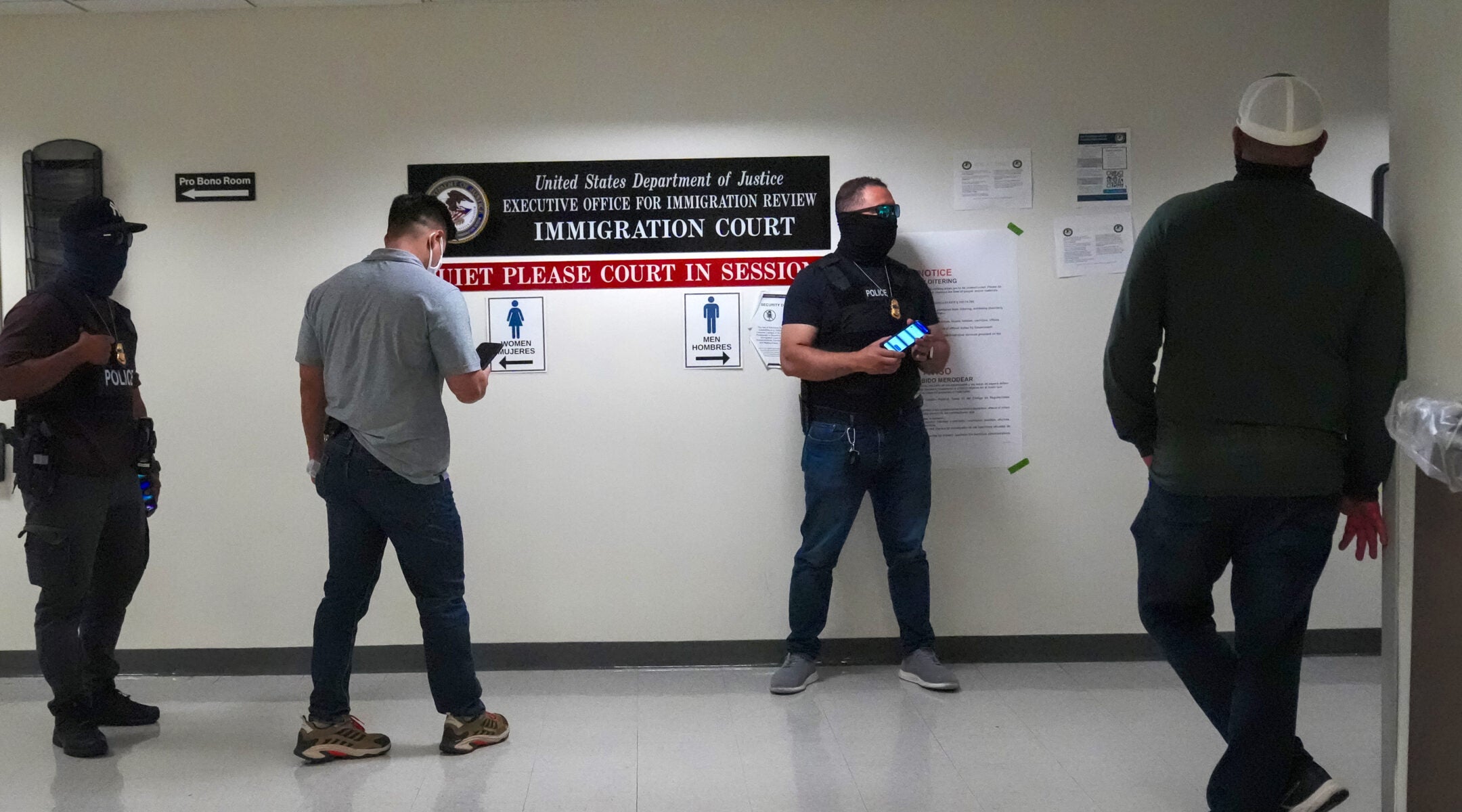

But this year, in the waning days of Elul, when Jews began reflecting about the upcoming High Holiday season, I stood before three different judges — not in traffic court but in immigration court. And not as an attorney nor, thankfully, as a respondent — a foreign-born person charged by the Department of Homeland Security with violating immigration law and facing deportation proceedings.

No, I stood as a privileged white American naturalized citizen. I stood as an online-trained ABA court observer to monitor and document immigration court hearings, as a way of holding America’s court system accountable. I stood as a rabbi spiritually tormented by today’s troubling headlines and disturbing images regarding our government’s treatment of immigrants, the very strangers the Torah commands us 36 times to welcome. And I stood as a fellow human filled with empathy for those who bravely traversed perilous terrains, with children in tow, to reach the fabled, promised land of freedom, safety and opportunity.

Some respondents have bounced around the courts since 2013. Each appearance is fraught with fear, trembling, and angst about their fate. After all, a courtroom setting can be daunting and foreboding. I sat just 10 feet — or a virtual connection away — from these modestly dressed respondents who stare nervously at the judge. And I thought about the coming Yom Kippur holiday, when I would ponder God’s decree about me in the Book of Life. Would it be a decree of life or death, prosperity or hardship?

I quietly imagined these frightened immigrants reciting their own personalized version of our millennium-old Unetanah Tokef prayer:

Who shall live freely in America AND who shall be forcibly (or by self removal) shipped to countries rife with political persecution? Who shall remain united with loved ones AND who shall fester in a rat-infested jail cell? Who shall realize their fondest dreams AND who shall return to a land where opportunity is harvested only by the elite? Who shall have access to Costco’s abundances AND who shall barely survive on crumbs? Who shall leave the courtroom with renewed hope AND who shall leave hopeless? Who shall be lucky to get another deportation delay AND who shall be unlucky to receive notice of final removal from the United States?

A 50-ish woman from Central America appeared without counsel, because she couldn’t afford one. U.S. law stipulates that she’s entitled to one, but at her own expense. ICE agents came to her door looking for someone who did not live in the house. Perhaps seeing opportunity to meet a quota of arrests, they asked for papers she did not have. They hauled her away. Now, wearing an ankle monitor as a flight risk, she told the judge in broken English, in a barely audible, trembling voice: “I have lived here for 20 years. I have a family, a job. I’m not a terrorist.” The judge gave her another 60 days to find a lawyer, pro-bono or not. Or else.

A young woman said she wanted to self-deport. The judge, surprised, offered her more time to file papers attesting to her marriage to a U.S. citizen (possible grounds for relief from removal). She replied: “I already have tickets to fly back next week. I fear ICE agents may apprehend me outside this courtroom.”

The stories are heartbreaking. Only those with a hardened heart of Pharoah would be dismissive of the human tragedies revealed in their chilling stories.

Each day I listen intently while feverishly recording the courtroom’s verbal exchanges. I remind myself I’m here to assure a transparent and fair justice system. But will my modest contribution matter?

Suddenly, on that first day in court, a thought struck me. The ABA strictly forbids observers from interacting with anyone in the courtroom during hearings. What about after the last case is heard?

I slowly stood up behind the railing as the room emptied. Seeing me, the judge asked, “Do you wish to say something, sir?” “Yes, your honor. May I first compliment your Honor on today’s hearings?” Appearing a little stunned by this uncommon question, she replied, “Go ahead.” I proceeded to compliment her integrity, empathic exchange with the respondents and fair-minded decisions.

I paused and told a story of my own. “With your honor’s permission, I’d like to give personal context to my appearance today,” I said. “I am in my 80s, a child of Holocaust survivors. In the late 1930s, my grandparents applied for a U.S. visa for asylum. They were denied. They were subsequently murdered by the Nazis.”

Silence. You could hear a pin drop. The judge, placing her hand over her heart, then replied: “I am truly sorry for your loss. Now I understand why you are here.”

Fleetingly, I felt as if I had spoken truth to power. Will that judge remember my words? I can only hope so, for the sake of future respondents who stand before her.

On this Yom Kippur, I pray that the Almighty above judge us mercifully, both individually and collectively as Jews, and renew us for another year in the Book of Life. May God’s abounding mercy soften the hearts of immigration judges across this land, and compassionately answer the fervent prayers of the strangers in our midst.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.