FARMINGTON HILLS, Michigan — The bishop solemnly walked through the photos and illustrations documenting Nazi-led antisemitic sentiment, aided in several cases by Catholics, that doomed the Jews of Europe.

At one point he proudly noted he had befriended the nephew of a prominent Dutch Catholic resistance figure.

And when prompted to theorize why one Holocaust survivor might have taken such great effort, after the war, to sew his camp uniform back together, he gamely offered, “So people will remember.”

So far, so good for a religious leader’s interfaith visit to a Holocaust museum. But when Detroit Archbishop Edward Weisenburger spoke briefly to reporters at the conclusion of his Monday tour of the Zekelman Holocaust Center, he offered another thought — one about the present day.

“I’m deeply, deeply troubled by what’s happening in Gaza,” Weisenburger said when asked for his thoughts on the war. “And I feel that it would be a betrayal of everything that this magnificent museum stands for if we were to ignore the suffering, the pain, the unjust slaughter of tens of thousands of people.”

Following these comments, Weisenburger entered a closed-door session with local Jewish leaders, including Jewish Federation of Detroit representatives. If they were bothered by his takeaway on Gaza, they didn’t say.

“We’re a historical museum, so we don’t really comment on current events,” Rabbi Eli Mayerfeld, the museum’s CEO, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

The archbishop’s visit was part of a larger interfaith outreach effort, including other sit-downs with Jewish leaders, he has undertaken since being appointed to Detroit in March. But it was also a snapshot of a delicate interfaith moment Jewish communities are trying to navigate as Israel’s campaign in Gaza steadily loses global support. The Detroit area is home both to a large Jewish community, which is among the largest regional donors to Israeli causes, and a large Arab American community which has forcefully advocated for Palestinians. Jews and Jewish centers in the area have been targeted by activists since the outbreak of war in Gaza that began with the Oct. 7, 2023 Hamas attacks.

Both Pope Francis, who died in April, and Pope Leo have forcefully advocated for civilians in Gaza.

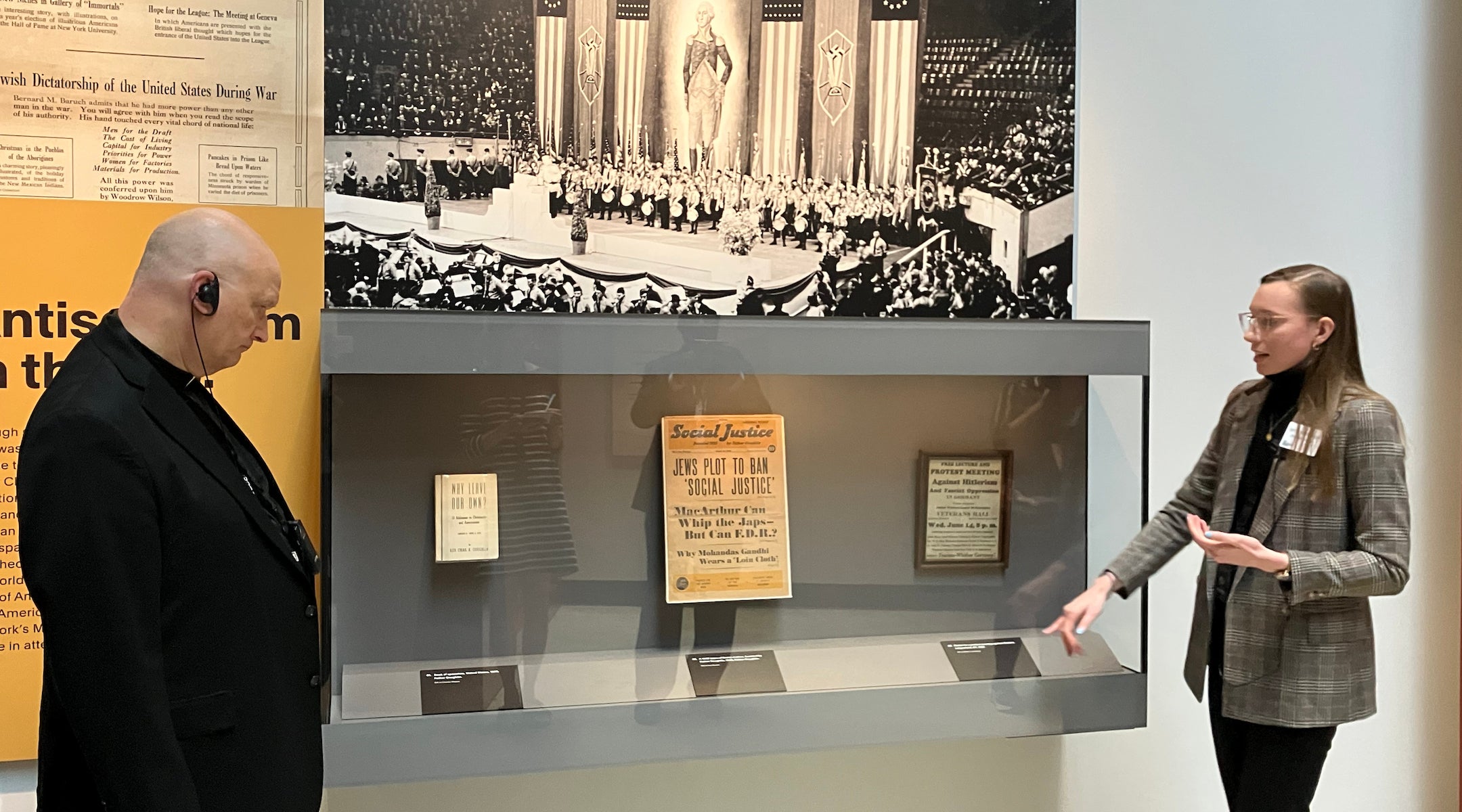

Detroit Archbishop Edward Weisenburger tours the Zekelman Holocaust Center in Farmington Hills, Michigan, Aug. 18, 2025. Weisenburger has vocally advocated for citizens in Gaza amid Israel’s ongoing war in the region. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

Detroit Archbishop Edward Weisenburger tours the Zekelman Holocaust Center in Farmington Hills, Michigan, Aug. 18, 2025. Weisenburger has vocally advocated for citizens in Gaza amid Israel’s ongoing war in the region. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

And in Detroit, where Jews and Catholics have long eyed each other warily owing to a painful local history, the sight of a Catholic leader touring a local Holocaust museum was particularly poignant. On prominent display at the center: 1930s-era writings by Father Charles Coughlin, the populist “radio priest” from Royal Oak, Michigan, who was one of America’s loudest voices stirring up antisemitic sentiment in the run-up to the war. Coughlin enjoyed the full backing of Detroit’s bishop for years while operating from his parish, the National Shrine of the Little Flower.

The museum’s education manager Jamie Miskowski, herself a Catholic, served as Weisenburger’s tour guide and drew special attention to the Coughlin section. Coughlin’s agitation, Miskowski said, was one of several examples of the Catholic antisemitism that helped lay the groundwork for the Holocaust, and one with a particularly “unfortunate” local connection.

In recent years, the Shrine of the Little Flower has more directly confronted Coughlin’s antisemitism and has sent its own delegations to the museum. Asked about what else he thinks the Shrine could do to further address Coughlin’s legacy, Weisenburger was noncommittal.

“I’ve only been here a few months, so this is all still very new to me,” he told JTA. “So many people come from different perspectives, so I’m still kind of learning the archdiocese. I would say the key is, every group must always be willing to face the truth, the truth of what happened in the past and the truth of what is happening today.”

On the significance of the archbishop’s visit more generally, Mayerfeld acknowledged that the Jewish community “is looking for allies.” He hoped the day’s visit would help. “I think overwhelmingly, the public is not antisemitic, but they need information. They’re not aware of the history. And I think having a partner like the archdiocese here helps to educate,” said Mayerfeld.

In a statement to local media, the federation said “we deeply appreciate” Weisenburger’s visit, adding, “As our community grapples with the rise of violent antisemitism in the United States, it is more important than ever to build bonds and foster understanding with other faith communities across metro Detroit.” The statement did not mention the war in Gaza.

The archbishop, a devotee of the late Pope Francis who previously oversaw the diocese of Tucson, Arizona, has been more outspoken about other issues he sees as within his purview. That includes Gaza, which Weisenburger said he visited 12 years ago and called “very dear to my heart.”

He recently urged Detroit-area Catholics to be “most generous” in donating to aid groups to help alleviate what he called “catastrophic levels” of hunger in Gaza. In a May op-ed on the occasion of Pope Leo XIV’s coronation, Weisenburger noted he has participated in remembrance events for Israeli victims of the Oct. 7 attacks. He also urged Catholics to remember Francis’ own calls to end “Israel’s campaign in Gaza,” which he wrote included “a blockade of humanitarian assistance — most notably of food — which has resulted in a global outcry.”

The Vatican has expressed grave concern about the situation in Gaza, where humanitarian conditions are grim following an Israeli blockade and subsequent limitations on aid that have prompted widespread concerns about a hunger crisis, and where the Israeli military is preparing to widen its operations. For a time Francis spoke daily with leaders of the region’s Catholic minority population and turned the Popemobile into an aid vehicle for the area. Last month an Israeli strike damaged Gaza’s only Catholic church, which Vatican officials condemned and Israel said was the result of “stray ammunition.”

Meanwhile, Weisenburger has taken other measures in his brief time in Detroit that speak to an effort to change the culture at the archdiocese in a way that would be favorable to Jewish relations. Shortly after arriving, he sharply curtailed area Catholics’ ability to recite the Latin Mass, a traditional liturgy that has long been a source of contention because it contains calls for Jews to convert (Francis had taken similar steps from the Vatican). He then fired three ultra-traditionalist professors at a local seminary who had fought back against such reforms.

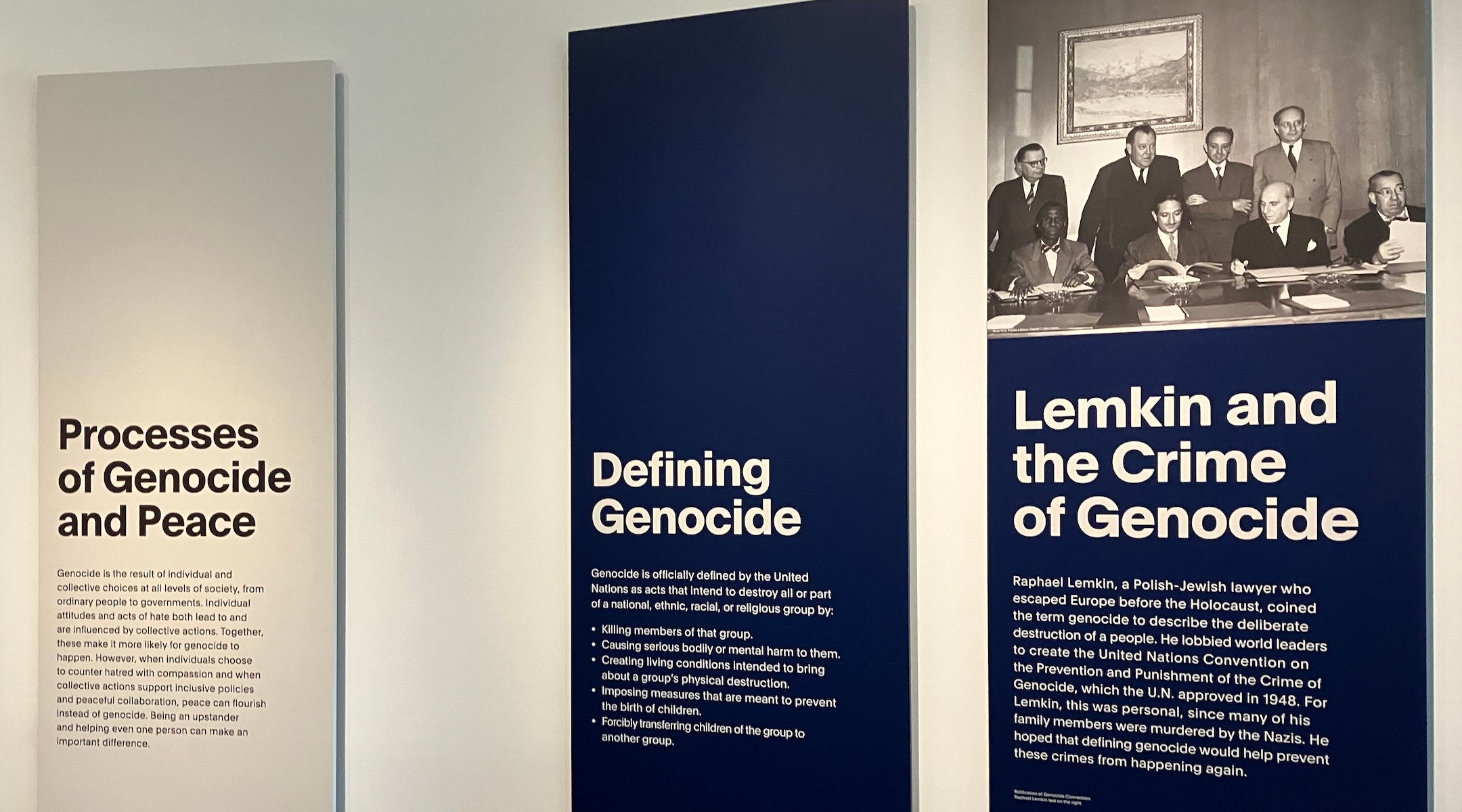

A room in the permanent exhibit of the Zekelman Holocaust Center in Farmington Hills, Michigan, discussing the origins of the term “genocide,” Aug. 18, 2025. The center’s permanent exhibit space was overhauled in 2024. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

The Holocaust center did not frame Weisenburger’s visit around these issues, nor around Gaza; the museum instead said it was a general outreach effort given the archbishop’s recent arrival to Detroit. But the center, like some other Holocaust museums, has been caught in other Gaza-related controversies since the outbreak of war. Last year the museum cut a local Holocaust survivor from its speaker roster amid that survivor’s vocal anti-Zionist activism; the survivor has participated in protests held outside the museum itself. (That survivor, Rene Lichtman, died earlier this year.)

“Jewish identity, then and now, can include religion, but also can be centered around culture, peoplehood, or a connection to the land of Israel,” Mayerfeld said in opening remarks to the archbishop.

The museum overhauled its permanent exhibition last year, in part to increase its focus on survivor stories. The redesigned space opens with a short film depicting centuries of Jewish life in Europe; visuals throughout are now lighter on images of emaciated bodies from concentration camps and heavier on stills of Jewish life as it existed before the war. At the end, following a viewing area for an “Anne Frank tree,” the museum’s final room is devoted to the concept of “genocide” after the Holocaust, and the Polish-Jewish lawyer, Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term. One plaque reads “Defining Genocide” and includes, as one example, “Creating living conditions intended to bring about a group’s physical destruction.”

Even as its CEO insisted it was not the museum’s place to comment on current events, this room provides visitors with notecards containing the phrase “What can we do?” and encourages them to write down ways they would take their lessons from the museum into the world. “When antisemitism and other forms of hate arise,” a plaque reads, “we must ask ourselves and our governments: What can we do to make a difference?”

On the day of the archbishop’s visit, one anonymous note on the wall read, in all caps, “INCREASE AID!”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.