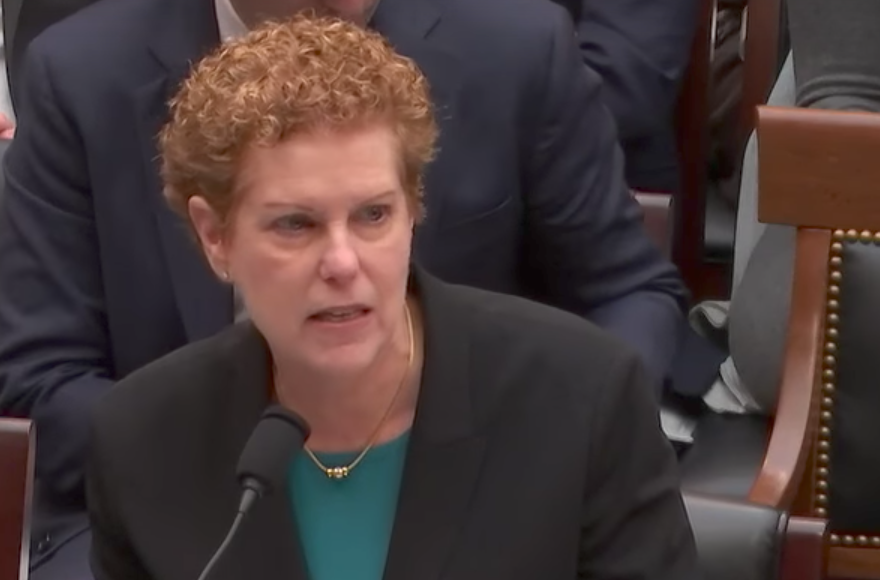

In December 2023, Pamela Nadell, a professor of Jewish history at American University, testified alongside the presidents of Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania and MIT at a congressional hearing on antisemitism on college campuses.

If you don’t recall her testimony, don’t blame her or yourself: That’s the hearing when two of the presidents, Harvard’s Claudine Gay and Penn’s Liz Magill, appeared to equivocate on how their schools were handling charges of antisemitism, and consequently resigned under pressure.

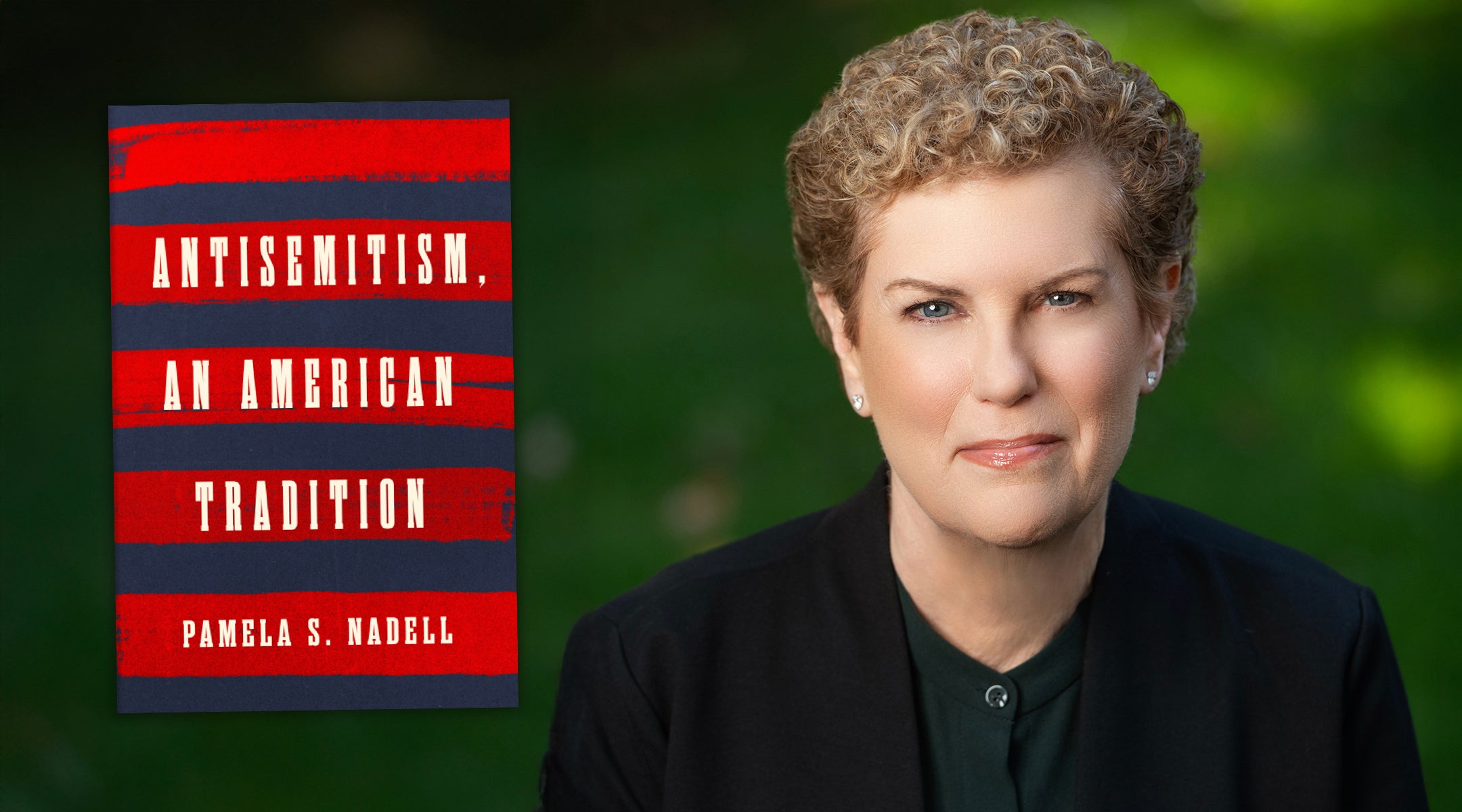

At the time, Nadell was at work on a history of antisemitism in America, and couldn’t have known that she would become a supporting player in a key moment in that story. Now she has completed the book, “Antisemitism, an American Tradition,” in which she chronicles the different forms Jew-hatred has taken from colonial times to the present.

Puncturing the largely flattering story of an America that created the conditions for Jews to flourish as never before, the book shows, she writes, “how powerfully antisemitism has coursed throughout American history and how much it impacted the lives of America’s Jews no matter where they lived.”

It’s a history that includes Peter Stuyvesant’s efforts to oust the 23 Jews who had recently landed in what is now New York in 1654; the discrimination Jews faced in the Revolutionary and Civil War eras; the anti-immigration fervor of the early 20th century; the virulent isolationism and pro-Nazism of the 1930s and 1940s, and the purported “Golden Age” that saw Jews come into their own after World War II.

It concludes with the current-day explosion of antisemitism on the right and the left: the shootings at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh and the white power marches in Charlottesville, Virginia; pro-Palestinian demonstrations that, she writes, “erased” the line between anti-Zionism and antisemitism, and the killing of two Israeli embassy staffers outside a Jewish event in Washington, D.C.

While Nadell believes that Jews are facing a “high tide” in terms of the psychological impact of what others have called the “enduring hatred,” she also stresses that hers is not a “post-Oct. 7” book. If anything, the impetus for writing the book was a remark made by a colleague years before the start of the current Israel-Hamas war, who noted how antisemitism appeared to be “all over” her previous book, “America’s Jewish Women: A History from Colonial Times to Today.”

“I was stunned,” she said. “I went back and I looked, and I had some story about an anti-Jewish encounter in every chapter. Which brings me back to the point that to be a Jew, no matter where you live or when, is to encounter anti-Judaism or antisemitism. It’s just part of that experience.”

Nadell also believes her book is one of the first to see American antisemitism through the eyes of its victims. While Jews have flourished since World War II, she takes seriously their hard-to-account-for but persistent insecurity. Call it paranoia, but the psychological impact of antisemitism, despite the Jews’ outward signs of prosperity, is “profound,” she said. “It shapes how Jews live their lives.”

Nadell, 73, is professor and Patrick Clendenen Chair in Women’s and Gender History at American University in Washington, D.C. She is a past president of the Association for Jewish Studies.

In our conversation Thursday, we talked about the distinction she makes between anti-Zionism and antisemitism, why the post-war years were less golden than they seemed and how the Trump administration is using antisemitism in its efforts to remake American universities.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to call the book “Antisemitism, an American Tradition”? What does that phrase capture?

The phrase is a nod to historian Tony Michels, who wrote an important article about 15 years ago pointing out that American Jewish historians had essentially ignored antisemitism in our histories. We wrote hundreds of books about how Jews engaged with America, but because we were products of our own time, we didn’t foreground antisemitism. Then Charlottesville happened, and then Tree of Life. After Tree of Life, many of us were meeting at the Center for Jewish History, under the auspices of the American Jewish Historical Society, and we wondered: How had we missed the story?

In “Antisemitism, an American Tradition,” historian Pamela Nadell chronicles how hatred of the Jews was a persistent theme in every era of U.S. history. (W.H. Norton)

What are some of the myths your book punctures about antisemitism in America?

I think many readers will be surprised by the persistence of Christian anti-Judaism, which surfaces from the very beginning, and why I write that it was carried over in the rucksacks of the colonists.

The other myth is that antisemitism in America was never or rarely violent. People think of the Holocaust, pogroms or the Inquisition when they hear “antisemitism,” and assume that American antisemitism was different and somehow benign. It was different, yes, but not harmless. Local attacks, arson, murders — they often never reached the national press, but they happened.

Can you unpack the distinction between Christian anti-Judaism and other forms of antisemitism?

They differ tremendously. I use the word “antisemitism” throughout, but it wasn’t coined until the 1870s. “Anti-Judaism” is theological, rooted in the charge that Jews killed Jesus. “Antisemitism,” as coined by Wilhelm Marr and others in Europe, was race-based — a belief that Jews were a racial threat to society, but they’re not looking to blame them for the murder of Jesus.

In America, because the debate over whether we are a Christian nation has never gone away, Christian anti-Judaism and antisemitism are braided together. I didn’t watch the funeral of Charlie Kirk, but I did read about the comments [by Tucker Carlson] repeating the gospel stories about the Jews murdering Jesus. Evangelical support for Israel, for example, is tied to their belief in the coming of the Messiah. So I don’t think you can separate them.

I am always amazed, and was so in reading your book, about how both the right and left have variously used antisemitism and anti-Jewish conspiracy theories as a proxy for whatever else might be fanning the flames of their extremism — economic discontent, isolationism, nativism, anti-capitalism, anti-colonialism. I almost see that as the defining feature of “American” antisemitism, and wonder if you agree.

That’s right, but it’s not unique to America. In Europe, you have “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” the Dreyfus Affair, Soviet antisemitism. Antisemitism flourishes on both the right and the left. That’s something I was careful to stress, because as I was finishing the book — I was writing the book in 2022 and 2023 — Oct. 7 happened, and suddenly all the focus was on antisemitism on the left, especially on campuses. But antisemitism from the right is just as virulent. American history shows it’s always been present on both sides.

But I guess my question is also about that most perennial of questions: Why the Jews? Why does this small minority become the scapegoat again and again?

Robert Wistrich called antisemitism “the longest hatred.” Antisemitism adapts. Whatever people are unhappy about, they can map it onto Jews. In a New Yorker interview with Isaac Chotiner, David Nirenberg [author of “Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition”] tells the story of being on the subway a few weeks after 9/11. One rider said, “It’s the Jews’ fault — they made New York the capital of capitalism.” The other replied, “And because they killed Jesus.” You can’t separate the motives. One is economic, the other theological, but they converge on Jews.

Henry Ford is the classic American example: Whatever was wrong with society, he blamed on Jews.

You devote a chapter to what some call the postwar “Golden Age” of American Jewry, but warn in the chapter title, “No Age is Golden.” What led Jews to talk about that era, roughly from the end of World War II to the 1970s, or maybe to the year 2000, as a halcyon time, and in what ways did it fall short?

It depends on how you look at it. It didn’t happen overnight. “Gentleman’s Agreement” [Laura Z. Hobson’s novel that, Nadell writes, “would expose the disgrace of genteel American antisemitism”] came out in 1947, but quotas and restrictions lingered for years. Still, real changes happened: It’s a golden age because so many of the structural barriers to Jewish success in America ultimately fell. Country clubs admitted Jews, elite universities dropped quotas, the Fair Housing Act meant restrictive housing covenants were no longer enforced, Jews rose to leadership in business and politics. We get a vice-presidential candidate who’s Jewish, and a [Senate majority leader] who is a proud Jew. So that’s the reason for the perception of the Golden Age.

But when I talk to Jews who lived through that era, I hear a different story. People remember being pelted with pennies, taunted with slurs. After Oct. 7, I kept hearing from people who said, “I never thought I’d live to see this,” and yet, in the same breath, recalled childhood antisemitism. So the Golden Age was real, but it was also never free of hatred.

Many pro-Palestinian demonstrations after Oct. 7 “erased” the line between anti-Zionism and antisemitism, writes Nadell. Above, scenes of the reinstated Gaza Solidarity Encampment at Columbia University on its fourth day, April 21, 2024. ( Abbad Diraneyya/Wikimedia Commons)

If some saw the post-war years as the high point in terms of Jewish acceptance, of their cultural and political impact, what was the nadir?

Historians long called the 1930s the “high tide” of American antisemitism — plots to hang Jews in Hollywood, pro-Nazi rallies, Father Coughlin [the influential antisemitic priest] on the radio. But I’ve been saying for a while now that we may have to rename that period. Because of antisemitism from both left and right, and especially because of social media, I think we are living through a new high tide of American antisemitism right now. That’s because of the violence coming from both the right and the left.

I’d like to push back on that somewhat: Despite the violent attacks in Pittsburgh and Poway, California, and the eruption of anti-Zionism on campuses and in the streets, Jews are disproportionately successful. Jews have flourished in academia and in the professions, law firms hire Jews, most Jews live in prosperous neighborhoods. Does antisemitism really have the power to affect Jewish lives?

You mean structurally?

Yes, that’s a better way to ask the question.

Structurally, no. Jews are not going to face quotas in universities again. But I come at this from a slightly different angle. When I toured for my last book, I began asking audiences if they had ever experienced antisemitism. The stories poured out — incidents from 50 years earlier, told in vivid detail, with pain and anguish.

What jumped out at me then, and what I have said publicly since, is that — even if other people want to say their anti-Israel positions are not antisemitic — it’s how Jews internalize what they face as antisemitic that has a lasting effect on Jewish lives. Now, some of this may be because I’m married to a clinical psychologist, but what we’re seeing now is that, psychologically, the impact is profound. It shapes how Jews live their lives. I keep reading all these studies of the numbers of Jews who won’t disclose that they’re Jewish.

My son told me recently he was in an Uber. I called him and said, “Shana Tova.” He answered, “You too.” Later he admitted he hadn’t wanted to say “Shana Tova” out loud in front of the driver. That’s how antisemitism affects Jewish lives — by shaping behavior, by instilling caution.

The current debate — and any present or future assessment of the degree to which we are living through a new wave of antisemitism — often centers on when anti-Zionism crosses a line to become antisemitism. The Anti-Defamation League has its own way of determining when an act is antisemitic or not. What criteria did you use in describing an act or statement as antisemitism?

For me, calling for Israel’s destruction is absolutely antisemitism. Criticizing Israeli policies is not — Israelis themselves do that every day. But increasingly, “Zionist” has become a slur, a new code word, just as “Jew” was pejorative in the 19th century, so that Jews themselves preferred to call themselves “Israelites.” NYU’s student conduct code even recognizes that “Zionist” can be used as a term of hate.

But an anti-Zionist Jew, for example, might argue that they don’t have an issue with an individual’s religious beliefs or biology, but are opposing anyone who chooses to support what they consider an oppressive, colonialist state.

I’ve been in conversations with colleagues who have done that, saying “Oh, I’m not an antisemite, but Israel has no right to exist.”

How do you respond?

My response is, “You and I are never going to agree on this.”

Your book is not prescriptive, but did you find a common theme in what approaches work best to combat antisemitism?

What hasn’t worked is the belief that education will end antisemitism — “If only people knew the Jews, they wouldn’t hate us.” That’s been said since the 19th century. Now we have a huge new National Endowment for the Humanities grant [to the conservative Tikvah], NEH’s largest grant ever, which is going to educate about the Jews and that is optimistic that educating about the Jews will change people’s attitudes towards them. And yet the reality is, Jews are the most favorably regarded religious group in Pew surveys, yet millions of Americans still hold antisemitic stereotypes.

What does help is allies. When government or institutions act, antisemitism can be checked. But there will always remain that irreducible percentage of people — maybe 10% of Americans — who hold strong antisemitic beliefs.

Speaking of allies, as a historian, have you ever seen anything similar to what’s going on now where the government is committed to fighting antisemitism, but is doing it in a way that’s going right at your livelihood — that is, punishing universities and withholding federal funds and using antisemitism as, depending on your politics, a reason or an excuse for demanding changes, from scrapping DEI programs to disclosing “foreign influence” to banning transgender students from women’s sports. Have you seen this before and, to ask another perennial question, is it good for the Jews?

It’s bad for the Jews. You’ll recall that in December 2023, I testified alongside the university presidents — two of whom later lost their jobs. Just a month before, Trump was campaigning on taxing university endowments to fund a new “anti-woke” university. That idea went into the dustbin, but antisemitism became the pretext for going after higher education. In 2021 J.D. Vance gave a speech saying conservatives need to “aggressively attack the universities.” Antisemitism is giving them the coverage to do that now.

Pamela Nadell testifying on antisemitism before a House Judiciary Committee on Nov. 7, 2017, three months after white supremacists chanting “Jews will not replace us” paraded at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. (Screenshot from YouTube)

And why is that bad for the Jews?

The danger is that when the tide turns, Jews will be blamed for the diminishment of American universities, for the loss of their global standing. That’s a disastrous place to be.

With all this in mind, are you optimistic or pessimistic about the Jews’ place in America and the waning of antisemitism?

I take solace in history. After the high tide of the 1930s, things improved. My hope is that will happen again. My concern is the unprecedented role of social media, which amplifies antisemitism in ways we’ve never experienced. Campus encampments declined last year, vandalism declined, but antisemitism online exploded. That’s what worries me most.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.