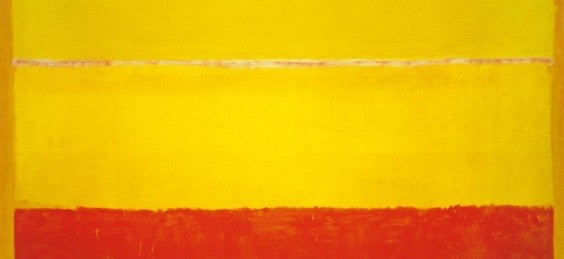

Before Mark Rothko’s famous rectangles of color were found in college dorms everywhere, before he became a key figure of Abstract Expressionist painting, he was born Marcus Rothkowitz in 1903 in Tsarist Russia.

His father, Yacov, was a self-educated secular pharmacist, but deadly pogroms in the Pale of Settlement convinced him to enroll Marcus, his youngest child, in a yeshiva. Whether it was a sudden burst of piety or an effort to keep the army from drafting his son isn’t clear.

But what is clear in Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel, Annie Cohen-Solal’s masterful Rothko biography is the role Judaism played in his career. He battled Yale’s anti-Semitism, the anti-Modernist attitudes of the 1930s and 40s, and the critics who derided his canvases as “handsome wall decorations.” He befriended Jewish collectors and curators. And his work shifted from mythological to surrealist to abstract as he sought a unity of vision, motivated by the principle of—who knew?—tikkun olam.

Rothko ended his own life after a difficult divorce and declining health. Unfortunately, he did so before seeing the completion of that chapel, a serene structure in Houston, Texas filled with fourteen of the artist’s paintings. But the book ends on a positive note, with his children opening the Rothko Art Center in Daugavpils, Latvia (formerly Dvinsk, Rothko’s hometown) and restoring its last remaining synagogue in 2013, a century after their father set sail for America.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.