WASHINGTON (JTA) – Offer an open hand or a closed fist — or maybe both. Name names. Don’t name names, hint. Quietly adjust wording.

Welcome to the second week of the World of Trump, Jewish organizational edition.

Week 1 was fraught enough, with Jewish statements marking Donald Trump’s surprise election ranging from the confrontational to “it’s a new day” accommodation.

Then President-elect Trump named Stephen Bannon as his chief strategist.

The appointment of Bannon, formerly the CEO of Breitbart, the right-wing news site that has been the clearinghouse for the alt-right movement, has been the buzz in the hallways and at lunch tables at the Jewish Federations of North America’s annual General Assembly meeting here this week. More than 3,000 Jewish communal professionals and lay figures from 120 communities are attending.

Comments on the record, though, were rare, a reflection of the bafflement prevalent in the Jewish community at how to deal with a president-elect who has no experience in public office and won the presidency through a scorched-earth campaign.

The Anti-Defamation League and a range of liberal Jewish groups have condemned Bannon’s appointment.

“It is a sad day when a man who presided over the premier website of the ‘alt-right’ – a loose-knit group of white nationalists and unabashed anti-Semites and racists – is slated to be a senior staff member in the ‘people’s house,’” Jonathan Greenblatt, the ADL’s CEO, said in a statement Sunday evening after Trump made the announcement.

Bannon is believed to have authored the Oct. 13 speech Trump delivered in West Palm Beach, Florida, that cast his Democratic rival, Hillary Clinton, as part of a secretive international cabal of international financiers seeking world control — with the assistance of a servile media.

The speech did not mention Jews, but the themes were familiar to anyone with a memory of conspiracy theories featuring Jewish villains.

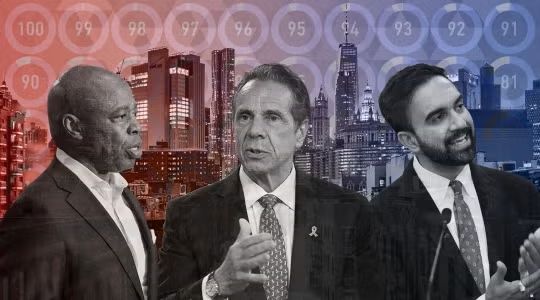

The sense that the campaign was dog whistling to white supremacists who embrace such theories was reinforced when in its last days, it ran an ad featuring excerpts of the speech accompanied by images of three prominent Jews.

Attendees at the JFNA General Assembly in Washington, D.C., Nov. 14, 2016. (Ron Sachs)

Such themes are prevalent at Breitbart, and while the site does not indict Jews per se — with rare exceptions — and is robustly pro-Israel, it also has become a nexus of the alt-right movement, where anti-Semitism has become prevalent, as well as misogyny, white supremacism and homophobia. The site does not remove anti-Semitic comments.

Bannon’s ex-wife has also, in an affidavit, accused him of disparaging Jews; he has denied the claims.

Breitbart employs Jews and confidants of Bannon insist he is not anti-Semitic. Jason Miller, a top Trump campaign official, told CNN on Monday that media examination of Bannon’s alt-right ties was “irresponsible,” and that the focus of coverage now should be on Trump’s planned policies.

Matt Brooks, the director of the Republican Jewish Coalition, speaking on a panel of Republicans reviewing the election at the Jewish Federations assembly, said he wanted to know more about Bannon, although he was confident from his statements that he was pro-Israel.

“I look forward to the opportunity to sit down with him and figure out how to work with him in the coming administration,” said Brooks, whose group, until the final days of the campaign, had avoided advocating for Trump.

The right-wing Zionist Organization of America in a release listed stories showing Breitbart as sympathetic to Israel or to Jews. Its director, Morton Klein, called on ADL to “withdraw and apologize for their inappropriate character assassination” of Bannon and Breitbart.

Liberal Jewish groups were unequivocal in their condemnation of the appointment.

“If President-elect Trump truly wants to bring together his supporters with the majority of the country that voted against him — by a margin that is nearing two million people, Bannon and his ilk must be barred from his administration,” the National Council of Jewish Women said in a statement.

The dilemma posed by Bannon’s hiring is one of access to the executive branch. It is the lifeblood of groups seeking to influence every nuance of Israel policy, as well as groups that partner with federal agencies on a range of domestic programs, including combating bias and preserving the social safety net.

Greenblatt said in a phone interview that the ADL will engage with the government on areas of common interest and strike a critical posture when necessary, as it has in the past.

“We’re prepared to engage optimistically and take the president at his word about bringing the country together but hold the new administration [to account] relentlessly on our issues, which means we’ll speak out when there’s a white nationalist as adviser,” he said.

That’s a formula that has worked with presidents until now – an array of Jewish groups, including the ADL, vigorously opposed last year’s nuclear deal with Iran, but maintained access to the White House. In its statement condemning Bannon’s appointment, the ADL took care to begin by commending Trump’s other major appointment of Reince Priebus, the Republican National Committee chairman, to be White House chief of staff.

But Trump ran a campaign that set new markers for invective, with the candidate hurling insults at reporters, politicians and just about anyone he didn’t like. The fear among Jewish leaders is that the White House will be run the same way.

Rabbi Jonah Pesner, who directs the Reform movement’s Religious Action Center, another group that condemned Bannon’s appointment, said — with resignation — that groups would likely lean more on Congress to advance their agendas.

“We network with Republicans and Democrats,” said Pesner, whose group has forged ties in recent years with Republicans seeking to protect persecuted Christians overseas and preserve voting rights for minorities, among other issues.

Pesner said he expected other organizations to step up.

“American Jewish organizations have to speak up with clarity and strength,” he said.

That did not appear to be happening, in the short term at least, among centrist Jewish organizations. The American Israel Public Affairs Committee refused to comment on Bannon, noting that it did not routinely comment on appointments. (It has, in exceptional circumstances, advocating in the mid-2000s for the Senate to confirm John Bolton as U.N. ambassador; Bolton is now on the shortlist for secretary of state.)

The American Jewish Committee also would not comment on Bannon.

“Of utmost concern is ensuring that policies proposed and put into place make good on President-elect Trump’s Election Night promise, for the benefit of all citizens of our too-divided country, and address the central concerns of the American people and our allies around the world,” said Jason Isaacson, its assistant executive director for policy. “Presidents get to choose their teams and we do not expect to comment on the appointment of every key advisor.”

At the Jewish Federations of North America, the umbrella body’s chairman of the board of trustees, Richard Sandler, counseled Jews unsettled by the election to reconcile with their antagonists and move on. Sandler suggested that Jewish Americans may have an overinflated notion of their importance.

“Let us stop to try delegitimate those who disagree with us,” he said. “We are less than 2 percent of the population of this great country.”

It is precisely the place of Jews in the American firmament that should guide their opposition to Trump, said Rabbi Jill Jacobs, who directs T’ruah, a rabbinical human rights group. Jews have former alliances with other minorities that feel threatened by Trump, and those friendships should now guide the community.

“Shtadlanut is a mode of survival,” she said, referring to the practice of some Diaspora communities of deferring to a leader in order to protect themselves. “But in the long run cozying up to authority never works. The danger for the Jewish community is cozying up to the administration to get something for ourselves but tearing ourselves from our allies.”

Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., a civil rights icon who has longstanding relationships with Jewish organizations, said younger Jews should draw inspiration from the alliances of the civil rights generation.

“We are all in the same boat,” said Lewis, who spoke at a General Assembly gathering at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture. “They burned synagogues and black churches because they are a symbol of those who march for justice.”

For Lindsey Mintz, the director of the Jewish Community Relations Council in Indianapolis who is piloting a program building alliances with African-Americans and Muslims, addressing the proliferation of anti-Semitic vandalism in the wake of the election was impossible to tweak apart from attacks on other communities.

“If this is civil rights 2.0, is the Jewish community going to show up — not just to talk but to listen and march,” she said in an interview at the conference. “That’s the question.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.