Allegations of Christian influence surface as World Zionist Congress election heats up

Around the time he was preparing to release his new book earlier this year, David Friedman, the former U.S. ambassador to Israel under Donald Trump, was approached by an advocacy group that focuses on fostering support for Israel among Christians.

The group, known as Israel365, asked Friedman to support a slate of candidates in next year’s election for the World Zionist Congress, a longstanding yet obscure organization that gives Jews around the world direct influence over Israel’s governance.

Established by Theodor Herzl in 1897, the congress and its representatives from Jewish communities around the world allocate $1 billion to Jewish causes every year and oversee Israel’s so-called national institutions, including the World Zionist Organization, which carries out the congress’ vision; the Jewish Agency, which plays a central role in immigration to Israel; and the Jewish National Fund, which owns 13% of Israeli land.

Coming at a pivotal moment in Israeli history, the upcoming election is widely viewed as an important contest in the battle for the country’s uncertain future, with new slates forming on both the left and, in the case of the group that approached Friedman, on the right.

Friedman agreed to the group’s request to use the title of his book, “One Jewish State,” as the name of the slate, signifying their shared support for strengthening Israeli control over the West Bank and their opposition to the two-state solution.

But last week, after the slate had gathered enough signatures to make the ballot, Friedman took to social media to address the “confusion” that made some people think he was involved in the slate.

“To clarify, I am NOT affiliated with any slate or candidates seeking election and I have not authorized anyone to speak on my behalf,” Friedman wrote.

He concluded, using the Israeli government’s preferred term for the West Bank, “I believe that the World Zionist Congress should support the Jewish communities located in Judea and Samaria and I support the slates which share this view.”

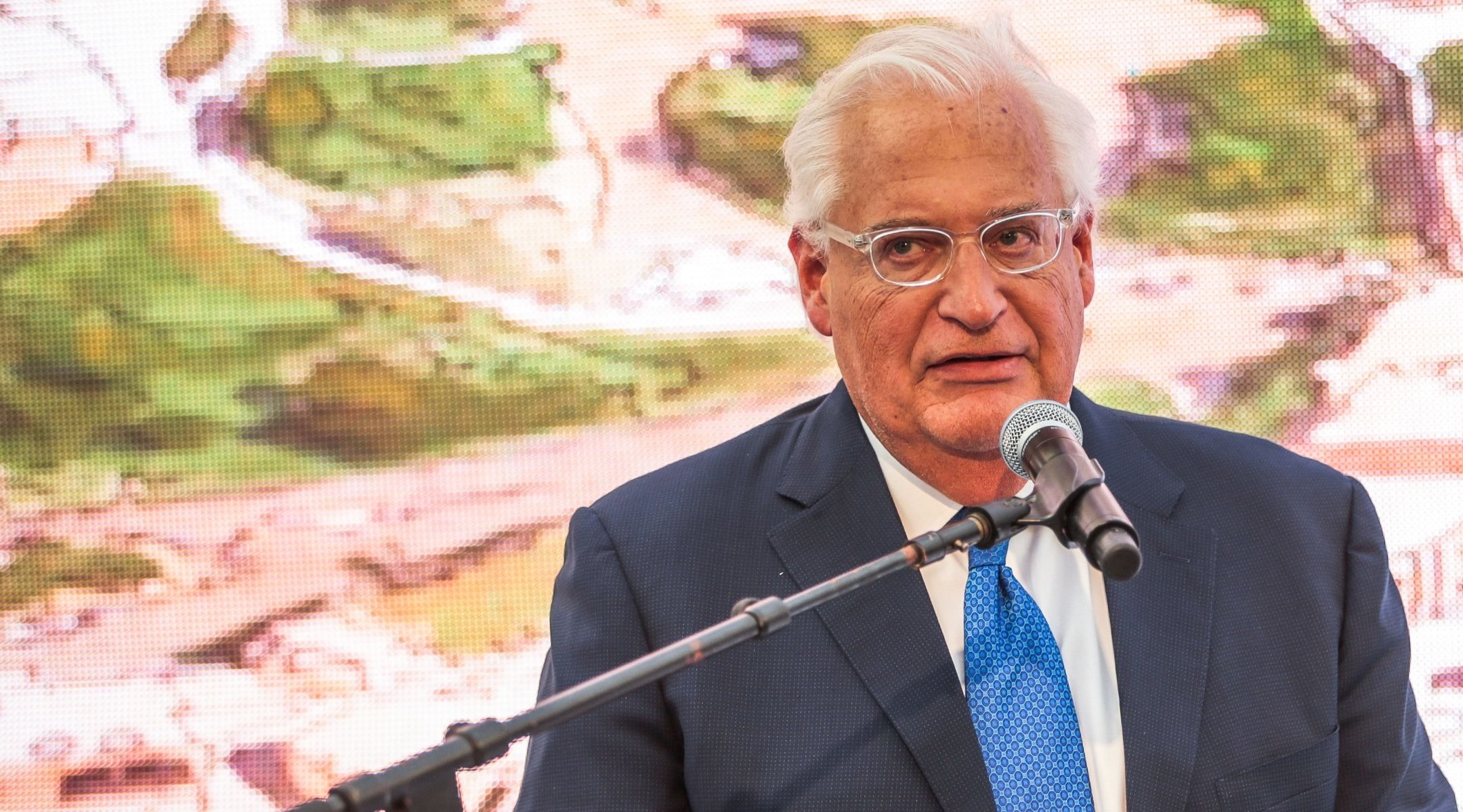

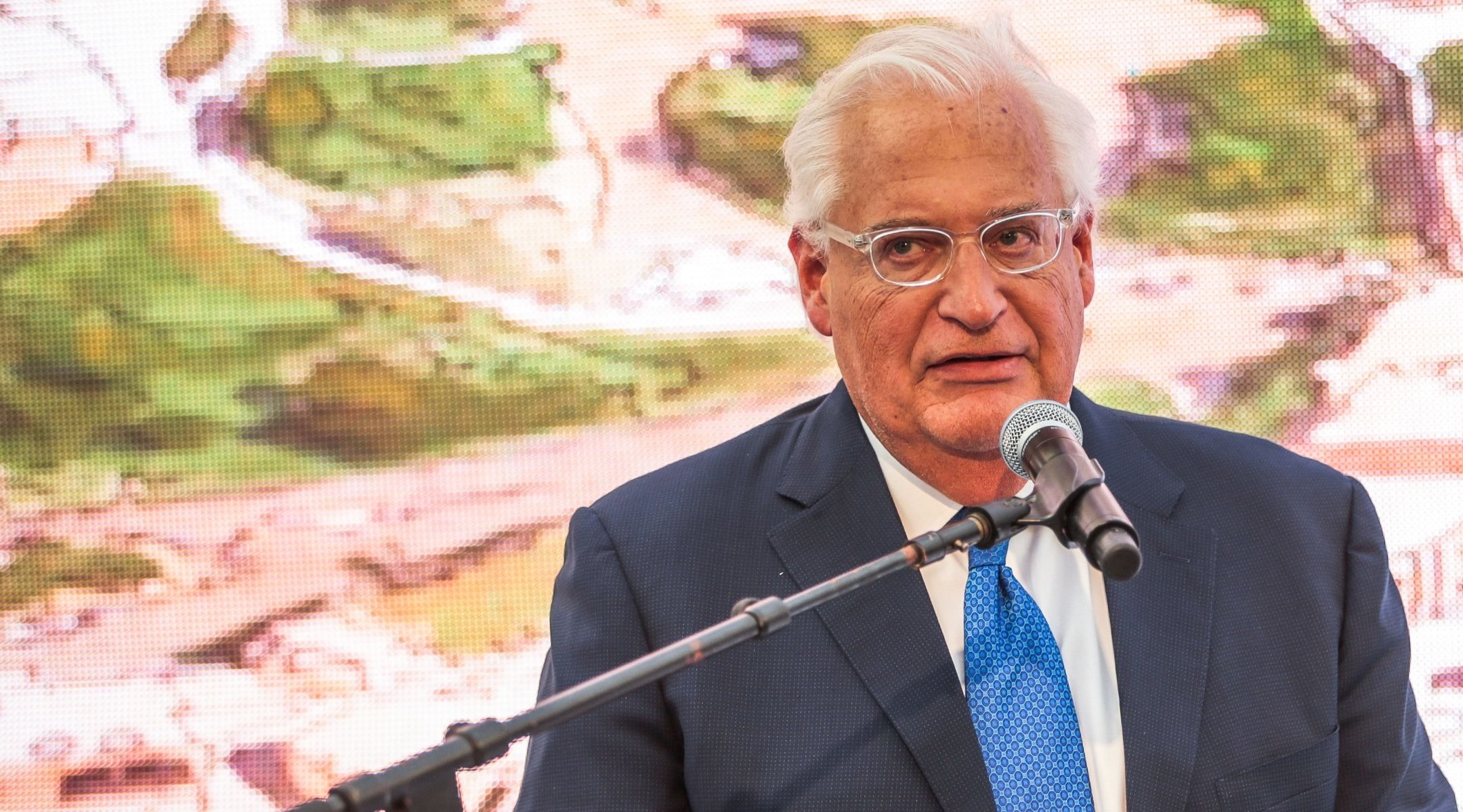

U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman speaks at the opening of Pilgrimage Road at the City of David archaeological site in the eastern Jerusalem neighborhood of Silwan, June 30, 2019. (Flash90)

Friedman’s post brought into public view an internal controversy, which has been marked by allegations that the slate had engaged in a bait-and-switch by using Friedman’s name to advance a hidden Christian agenda. Israel365, which denies the allegations, recently filed paperwork to change the slate’s name to Israel365 Action.

The controversy, which caused dozens of people to leave the slate, comes amid anxiety about Christian influence in an election that’s supposed to involve Jews only. With Israel’s government increasingly drawing its most reliable support Stateside from U.S. evangelicals, and with religious identity increasingly fluid, those who are tuned in early to the World Zionist Congress election say they fear non-Jews could cast ballots or otherwise shape the results in contravention of the election’s by-laws.

Such concerns have even prompted a change to the process for determining voter eligibility.

In the past, voters have had to state that they were Jewish and Zionist, criteria that exclude, for example, the tens of millions of Americans who identify as Christian Zionists. Now, voters will have to affirm that they are Zionist, Jewish, and that they “do not subscribe to another religion.”

Herbert Block, the executive director of the American Zionist Movement, which administers the election online in the United States, said the change was not prompted by the allegations against One Jewish State, but by a general desire to protect the integrity of the vote from people who may identify as Jews but should not be counted as such.

“Some members of our elections committee expressed concerns about Messianic Jews, or Jews for Jesus, or others voting,” Block said.

The coming election is shaping up to be hotly contested. At the deadline last month, nine new slates had gathered the requisite 800 signatures to register to run, on top of the 14 slates that have already existed since at least the last election in 2020. About 125,000 American Jews voted in 2020, out of the millions of American Jewish adults.

“There’s particular interest in the election — American Jews are more engaged with things related to Israel and Zionism, especially since the Oct. 7 attack,” Block said.

The slates represent different demographic groups, with variation by religious, ideological, and ethnic affiliation, but two major camps have emerged. On the left are those that support the two-state solution and a pluralistic Israel, and on the right are slates that want to bolster Israeli sovereignty in the West Bank and emphasize the country’s Jewish identity. Most of the new slates belong to the latter group.

Both sides are treating next year’s contest as a critical referendum on the soul of Israel, and they are battling over what’s seen as the biggest prize of the election: the American Jewish vote, which decides about one-third of the representatives in the congress. (The other two thirds are split between Israel, whose representation is predetermined according to the proportion of seats each party holds in the country’s parliament, and the rest of the world, which is difficult to fight over because of how widely Jewish communities are dispersed.)

Surveys show that American Jews favor the two-state solution and pluralism in Israel, but the question is, Which side will turn out to vote in greater numbers?

One of the people urging American Jews to vote is Yizhar Hess, the vice chairman of the World Zionist Organization, and the senior representative in the organization from the left-leaning Conservative movement of Judaism. He said he’s worried the religiously Orthodox and politically right-wing parts of American Jewry will be overrepresented — as they were after the last election — and add to the large Israeli bloc that already leans that way.

“It would be a historic calamity to allow Zionism to be controlled by only one side of the religious and political map,” he said in an interview. “If it happens, I am worried about the future of Israel and Zionism. The involvement of the entire Diaspora in the shaping of Israel is more critical than ever before.”

The screening of voters is based on the honor system, with each voter asserting their eligibility. But Block said his group does spot checks and looks for patterns that could indicate cheating. He said he doesn’t expect to face a problem of ineligible voters.

Even if the eligibility change is just a precaution, it reflects a growing fluidity in religious identity in the United States, where a fifth of people now attend houses of worship that don’t match their stated religious affiliation.

Even more to the point, the number of people in the United States who say they are Jewish but are not considered as such by conventional standards is significant. The Pew Research Center in 2020 estimated that 1.4 million American adults who identify as Jewish do not have a Jewish parent and do not consider Judaism their religion, perhaps because they are married to a Jew or because they are Christians who associate Jesus with Judaism. That’s in addition to 200,000 people who say they practice Judaism and another religion.

Then there are those who are religiously invested in Israel’s future but are not Jewish at all: evangelicals. They are the target constituency of Israel365, the nonprofit running the slate formerly named for David Friedman’s book.

A former candidate for the slate, Tilly Feldman is among the most outspoken critics of Israel365 Action, which she has accused of being a “Christian slate.” She said so on social media in response to Friedman’s post on X, joining another former candidate, Seth Leitman, who also called it a “Christian slate.” Leitman, an environmental activist from suburban New York, wrote, “Folks, we got grifted off this amazing man’s vision.”

Several others made similar points in off-the-record interviews with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Feldman, an activist for right-wing and pro-Israel groups in Los Angeles, told JTA she was thrilled to join an effort that appeared to be backed by Friedman. A video posted by Israel365 in July is titled, “Ambassador David Friedman endorses the One Jewish State party in the World Zionist Congress.”

What Friedman said in the 46-second clip can be interpreted in more than one way. He said he was flattered the slate chose to name itself after his book and cast the decision as an endorsement of his own efforts to start a movement. He then said, “I endorse their efforts.”

Feldman and others say the slate used clips like this to trick them into thinking Friedman had a formal role, and she complained to the AZM.

“I am writing to express my serious concerns regarding the slate One Jewish State and their misrepresentation of who they are and what they stand for,” Feldman wrote in the complaint, which she shared with JTA. “When I initially signed up, I believed, as did hundreds of others, that this slate was being led by ambassador David Friedman. This belief was central to their campaign and was a key reason so many delegates joined.”

She also urged people to defect from the slate. Dozens of people suddenly emailed AZM to withdraw their signatures, according to Block. (Even with the defections, Block said, the slate had more than enough signatures to register.)

In an email to JTA, Rabbi Tuly Weisz, the founder of Israel365, rejected the allegation and said the slate’s leadership had never misstated its relationship with Friedman.

“Since the war broke out, we have been working closely with him on behalf of Judea and Samaria,” Weisz wrote. “In the summer, we discussed with Ambassador Friedman calling our party ‘One Jewish State’ which at the time seemed like a great idea since his book was coming out a few weeks later, and he enthusiastically endorsed our slate. In the subsequent weeks, there was some confusion since his book and our movement were separate entities, so we decided to change our name to Israel365 Action.”

With the name change has come a shift in the slate’s platform. In the platform submitted to election officials months ago, the language hews closely to the principles found in Friedman’s “One Jewish State” book. But the slate’s new website contains additional language with a focus on the relationship between Israel and its Christian allies.

“Israel365 Action will direct resources towards engaging and educating the younger generation of Christians, thus ensuring that strong Christian support for Israel will continue into the future,” the website says.

Feldman said she would never have supported the slate to begin with if that were its platform.

“This is completely contrary to what many of us signed up for,” she wrote in her complaint. “It has left me, and others, feeling deceived and disillusioned by their lack of transparency and honesty.”

In his email, Weisz said that Israel365’s work with Christians is longstanding and well-known and that it was not concealed during the effort to gather signatures. He also said that the group, which counts many Christian followers, has taken care to communicate that only Jews are allowed to vote.

“For 13 years, Israel365 has carefully built bridges and nurtured relationships between Zionist Jews and Christians,” he wrote. “We hope that when Israel365 Action gets a seat at the Zionist table, we can help forge even stronger relationships between the Jewish community and our tens of millions of non-Jewish allies and thereby transform Israel into a ‘light unto the nations’ and the most beloved country in the world.”

Election officials do not plan on taking action in response to the complaints.

“I know they had some internal differences,” Block told JTA. “Every slate has its own internal issues and, unless something is a violation of some rule, then that’s not in our purview.”

Australia saw antisemitic incidents quadruple after Oct. 7, Jewish group reports

(JTA) — Jews in Australia experienced a record number of 2,062 antisemitic incidents over the year following Oct. 7, 2023, according to an umbrella group of Jewish organizations.

A new report from the Executive Council of Australian Jewry found that the number quadrupled from the previous 12-month period, when it tracked 495 incidents. The group detailed a rise across all categories of antisemitic incidents: assault, vandalism, verbal abuse and harassment, messages, graffiti, and posters and other public speech.

One of the most notable increases showed up in physical assaults — 65 Australian Jews were assaulted, up from 11 people the year before.

The report described a surge of high-profile incidents during the last months of 2023, in the immediate aftermath of Hamas’s Oct. 7 attacks on Israel. Those attacks and Israel’s ensuing war in Gaza have sowed division and turmoil in Australian society, rattling many members of the country’s Jewish community, who number about 120,000.

In one viral event two days after the Hamas attacks, a group of pro-Palestinian marchers shouted “F— the Jews” outside Sydney’s famed opera house. Witnesses also claimed to have heard “Gas the Jews,” but a police investigation reported the chant they heard was “Where’s the Jews?” — a finding that did little to comfort Jews in Australia.

Over the following weeks, several Jews were attacked in public, including a man in Sydney who was beaten by a group that demanded to know if he supported Israel; a boy in Perth who was slapped and called a “dirty Jew”; and a man in Melbourne who was called a “dirty rotten Jewish c—” by an attacker who threatened to kill him.

Another flashpoint came on Nov. 10, 2023, when police evacuated a Melbourne synagogue while a pro-Palestinian protest occurred nearby. Hours later, violence broke out between pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel factions.

ECAJ made a distinction between anti-Israel and antisemitic events. They said the report only included anti-Israel expressions in the context of a “clear and specific anti-Jewish element,” such as anti-Israel graffiti placed on a synagogue or the phrase “Free Palestine” shouted at someone only because they appeared to be Jewish.

The group’s deputy president, Robert Goot, was one of hundreds of Jewish creatives in a WhatsApp group that was doxxed in February, in a painful episode for Australian Jews that led to harassment and threats including against a 5-year-old Jewish child. Activists said they exposed the group, along with its members’ names, photos and personal information, because some participants lobbied for firing pro-Palestinian figures.

Goot was part of a conversation in the WhatsApp group about Antoinette Lattouf, a short-term radio presenter for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Members of the WhatApp group organized a letter-writing campaign against Lattouf for her pro-Palestinian views. Goot wrote that he received information the ABC would fire Lattouf because of her “stance on Israel” and encouraged other members to “keep writing” letters about her.

Lattouf was sacked on the same day as Goot’s messages and is suing the ABC for unfair dismissal. According to her claim, the stated reason for dismissal was a social media post sharing a Human Rights Watch report that said Israel was using starvation as a weapon of war.

The Australian antisemitism data follows a slew of tallies in other locations, many documenting a sharp rise in antisemitic incidents in the months immediately after the Oct. 7 attack. The Anti-Defamation League, the prominent antisemitism watchdog, found three times as many antisemitic incidents in the United States in the year after the attack as in the same 12-month period before — an unprecedented rise that was smaller proportionally than Australia’s.

Trump promised ‘all hell to pay’ if the hostages aren’t freed. What does that mean?

WASHINGTON — When Donald Trump vowed that there would be “all hell to pay in the Middle East” if hostages are not freed by the time he takes office, what did he mean?

The president-elect’s statement, coming after the revelation that American-Israeli Omer Neutra was killed on Oct. 7, 2023, was long on fury and short on details.

“Everybody is talking about the hostages who are being held so violently, inhumanely, and against the will of the entire World, in the Middle East — But it’s all talk, and no action!” Trump said in his statement posted on Truth Social, the social media platform he owns.

“Please let this TRUTH serve to represent that if the hostages are not released prior to January 20, 2025, the date that I proudly assume Office as President of the United States, there will be ALL HELL TO PAY in the Middle East, and for those in charge who perpetrated these atrocities against Humanity,” he said. “Those responsible will be hit harder than anybody has been hit in the long and storied History of the United States of America. RELEASE THE HOSTAGES NOW!”

Trump’s statement could just be bluster, said observers, or it could be a sign of real intentions: to target a regional military figure, or sanction countries that harbor Hamas officials, or create the conditions for Israel’s far-right politicians to accept a ceasefire deal. The president-elect could also be positioning himself to claim credit if a ceasefire is reached before his inauguration, some suggested. The unlikeliest scenario is that he would put American soldiers’ lives at risk in the battle against Hamas.

The immediate assumption among Israelis and American Jews who are in Trump’s orbit is that he was referring to the 101 hostages still held by Hamas in the Gaza Strip, though Trump did not specify further and a spokesman did not respond to a request for clarification.

“I want to thank President Trump for his strong statement yesterday about the need for Hamas to release the hostages, the responsibility of Hamas, and this adds another force to our continued effort to release all the hostages,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said in a statement.

But if Trump is referring to the Hamas-held hostages, what means could he use to pressure Hamas that haven’t already been exercised?

And most saliently, does his threat to hit the perpetrators “harder than anybody has been hit in the long and storied History of the United States of America” mean that the United States will attack Hamas directly?

According to analysts across the political spectrum, the answer to that second question is no.

“The concept of Americans coming back in body bags serving in the Middle East is not popular with Americans, not just with Trump,” said Shira Efron, the senior director of policy research at the Israel Policy Forum.

In the end, Efron said, Trump has a penchant for inflammatory rhetoric — and an aversion to war: In 2017, he threatened “fire and fury like the world has never seen” on North Korea for testing a nuclear warhead-carrying missile. Before long, they were meeting in Singapore.

“I just feel like these statements, I don’t know what he’s going to be — he could be much more experienced than last time and not make statements in vain, but I don’t know,” she said. “We have precedents to show that there are statements that are followed by different steps.”

What would those steps be? Israel, with American funding and weapons, has already been relentless in its pursuit of Hamas, killing much of its leadership, driving the rest into retreat and destroying much of the Gaza Strip’s infrastructure.

Israel, with American funding and weapons, has already been relentless in its pursuit of Hamas. Above, smoke rises after Israeli attacks on the northern Gaza Strip, May 21, 2024. (Ashraf Amra/Anadolu via Getty Images)

Trump ordered the assassination of Qasem Soleimani, an Iranian commander, in 2020. But this time, it’s not exactly clear which individuals he could target. Hamas has not named a leader since Israeli troops felled the architect of Oct. 7, Yahya Sinwar, in September.

The “hell” that Trump is threatening could be more applicable to Hamas’ enablers in the region, said Jonathan Schanzer, the vice president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a think tank that favors a more confrontational posture toward Israel’s enemies than the Biden administration has demonstrated. He suggested that Trump’s threats referred to non-military tactics.

“Saying ‘all hell’ may have been an exaggeration, but we have not imposed sanctions on the Turks believed to be harboring and financing Hamas,” Schanzer said in an interview. “We have not put full pressure on Qatar,” whose humanitarian aid bankrolled the Hamas regime, until recently. Qatar last month pledged to eject Hamas leaders from its territory, though it is not yet clear if that has happened.

Schanzer recommended threats to draw down major U.S. military presences in both countries. “The Turks have been supporting Hamas, and yet we maintain very sensitive weapons and personnel in Incirlik,” he said, referring to the U.S. airbase in Turkey, which is a member of the NATO transatlantic alliance.

EJ Kimball, an expert on counterterrorism at the U.S.-Israel Education Association, also called for pressure on Hamas’ enablers, although he acknowledged that it could be complicated by the complex relations the United States has with some of the countries, particularly Turkey.

“Turkey is a much bigger challenge, especially the NATO factor,” he said. “However, there are messages that can be passed along to Turkish leadership to understand the role that they need to play.”

One message, Kimball said, is that nations like Turkey and Qatar should not only expel and cut off funds to Hamas officials; they should extradite them to the United States.

Extradition to the United States is also one of a number of recommendations Richard Goldberg, a senior adviser to FDD, put together in late August. Another is to make clear to countries including Turkey and Qatar that the United States will not stand in the way of Israeli attempts to eliminate the Hamas officials wherever they are.

“The United States should also make clear to all countries that it supports Israeli efforts to kill or capture Hamas officials wherever they reside,” Goldberg, a staffer on Trump’s first term national security council, wrote in August.

That contrasts with the Biden administration’s uneasiness with Israel’s presumed assassination in July of Ismail Haniyeh, Hamas’ political leader, in Tehran. Biden officials feared the killing on Iranian soil would lead Iran to escalate its conflict with Israel, which proved to be the case.

But if Trump does turn the screws on countries that house Hamas leadership, Efron said it was not at all clear that the terror group would change course and release the hostages. Israel has decimated Hamas, she said, and Netanyahu has steadfastly resisted the group’s demands for a ceasefire: the release of Palestinians held prisoner in Israel, and a complete Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip.

“The question is, really, will Hamas care at this point?” Efron said.

David Makovsky, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, said Trump’s threat could be part of a joint ploy with the Biden administration to push Hamas toward a deal. In this scenario, Trump is playing bad cop opposite Biden’s good cop.

“We are hearing about how the transition teams, when it comes to foreign policy on both sides, are actually showing signs of working together, unlike after the last two rounds of U.S. elections,” said Makovsky, whose think tank has sources deep in the U.S. and Israeli governments.

Efron, whose group supports a two-state outcome to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, noted there were some positive signals a deal is pending, among them Hamas’ isolation after its Lebanese ally, Hezbollah, last week agreed to a ceasefire with Israel.

She said Trump may sense that a hostage deal is pending and may be putting out “bombastic” statements to take credit when it happens.

“Trump may be thinking, like, ‘there’s all this chatter. I’ll issue a statement, and if something happens, I can also take credit for it,’” she said.

Or, she suggested, the statement may be a means of pressuring far-right elements in Netanyahu’s cabinet, who have resisted any end to the war in Gaza, and who are hoping to reestablish Jewish settlements in the enclave.

Not only that, she said, Netanyahu may have solicited the statement for that purpose: She noted that Trump issued the statement after meeting with Netanyahu’s closest adviser, Ron Dermer.

“Trump, because he’s seen here [in Israel] as so pro-Israel, it‘s very difficult … to say no to this guy,” she said. If Trump pushes for a hostage deal, Efron said, “Netanyahu can go to Smotrich and say ‘What do you want? We can’t say no to him. He’s not Biden.’” She referred to the hard right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich. “Trump has leverage, here at least,” she said, referring to Israel.

Either way, Schanzer hopes Trump’s rhetorical shift will be enough to move the region to squeeze Hamas into a deal.

“Trump is changing the tone of the conversation,” he said. “But the conversation should have been changed a while ago.

New York awards record $63.9M in security funding for organizations at risk of hate crimes

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul said Tuesday that the state will direct a record $63.9 million in funding to organizations at risk of being targeted by hate crimes.

The funding will pay for physical security measures and cybersecurity at 336 organizations in the state, Hochul said in a statement. The organizations receiving the funding include nonprofits and community organizations at risk of hate crimes due to ideology, beliefs or their mission — including but not limited to religious groups.

Since 2021, New York State has awarded $131.5 million in similar security grants. The outsize sum comes after a year in which antisemitism has spiked in New York City, following the Oct. 7, 2023 Hamas attack on Israel that launched the war in Gaza.

“Creating a place where all New Yorkers feel safe, accepted and supported — no matter what may set them apart — is one of my top priorities, and I’m committed to using every possible tool to do just that,” Hochul said.

The funding will mostly go to organizations in New York City, the mid-Hudson region and Long Island. The state’s Division of Criminal Justice Services is informing applicants who will receive the funding on Tuesday. The governor’s statement did not disclose any information about the applicants or those receiving the grants, including how many applications were filed.

The state program comes in addition to more than $44.8 million in federal security funding for 223 New York religious organizations at risk of attacks from terrorists or extremists. That funding, from the Nonprofit Security Grant Program, will allocate $36 million to organizations in the New York City metro area and $8.8 million to other parts of the state.

The federal government will spend nearly $150 million more this year than it did in 2023 to secure religious institutions, a jump aimed at addressing a rise in antisemitism nationwide since Oct. 7, 2023. The federal total for this year is $454.5 million, the largest sum ever allocated toward the program.

The funding from the programs can cover measures including physical equipment such as reinforced doors, active shooter training and security contractors.

The funding is not specifically for Jewish institutions, but synagogues and other Jewish organizations use the grants for security and Jewish organizations have long advocated for the program. In this year’s federal allocation, 37% of recipients were Jewish groups, according to Jewish Insider.

Jewish New York lawmakers hailed Hochul’s announcement, including Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader, and state Assemblymember Jeffrey Dinowitz of the Bronx, who said in a statement that the allocation “sends a powerful message that hate has no place in our state.”

In New York City, Jews are consistently targeted in hate crimes more than any other group. Anti-Jewish attacks have surged since Oct. 7, 2023.

NYPD data released on Tuesday said Jews had been targeted in 21 hate crime incidents in November, more than the 19 crimes targeting all other groups combined.

An August report by Tom DiNapoli, the state comptroller, found that antisemitic hate crimes had increased by 89% from 2018 to 2023 across New York State.

In addition to security funding, New York legislators have sought to use legislation to protect Jews. Last week, Hochul signed legislation that criminalizes the removal of someone else’s religious garb, including kippahs and hijabs.

In Long Island’s Nassau County, the legislature passed a bill proposed by Israeli-American Mazi Pilip that bans masks at protests, a common sight at pro-Palestinian demonstrations that, according to law enforcement, has impeded the prosecution of people who perpetrate crimes. Jewish groups and other pro-Israel activists have pushed for a similar statewide law.

Hochul said earlier this year that she would back legislation expanding the number of crimes eligible for hate crimes prosecution, but the bill has not yet passed.

Loved ones gather to memorialize American-Israeli soldier Omer Neutra

Omer Neutra was killed more than one year ago, more than 5,000 miles away. But at his memorial service Tuesday morning on Long Island, the sanctuary overflowed with relatives, friends, Jewish leaders and at least one other hostage family.

Coursing through the crowd was the pain of learning — after nearly 14 months of unending hope and activism — that Neutra had been killed in battle alongside his fellow Israeli soldiers on Oct. 7, 2023, the day Hamas terrorists abducted his body to Gaza. It is still being held there.

“I pled for a sign of life; I didn’t get any,” said Orna Neutra, Omer’s mother, during the service at the Midway Jewish Center, a Conservative synagogue in Syosset, New York. “Instead, we received, on a daily basis for over 423 days, signs of hope and love: notes in our mailbox, flowers, meals, prayers for Omer and good deeds and thoughts from all over the world.”

She recalled the feeling of her son’s bear hugs.

“For over a year now, we’ve been breathing life into your being, my beautiful boy, with no physical sign back from you, but with hope and love of so many, we kept going and going, keeping you alive, speaking your name from every outlet and every stage, pushing away any hint of despair, not stopping to breathe or to take in the deep pain of your absence.”

Orna and Ronen Neutra, Omer’s father, have been among the most prominent activists in the movement to free the hostages held by Hamas in Gaza, of whom roughly 100, living and dead, remain captive. They traversed continents, spoke with President Joe Biden and President-elect Donald Trump, and appeared at the Republican convention in addition to many other venues.

They were joined at the memorial ceremony by Rachel Goldberg and Jon Polin, the parents of another American-Israeli hostage, Hersh Goldberg-Polin, who have also been among the most visible advocates globally for the hostages’ release. Goldberg-Polin and five other hostages were killed in captivity at the end of August; hostage families have called on Israeli leaders to make a deal for their release, so that the same fate does not befall those who are still alive.

“They did what they could, but they were taken hostage, and now it’s Israel’s turn to show its love and get him and all his team and everybody else back with more [than] 100 hostages still there,” Ronen Neutra said at the service. “One hundred-and-one families are craving, like us, to get them back.”

The family will sit shiva Tuesday to Thursday in Long Island, and will complete the weeklong mourning period in Israel.

Also in attendance were ADL CEO Jonathan Greenblatt; Nassau County lawmaker Mazi Pilip, an Israeli-American who ran for Congress earlier this year; and New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, who ordered all New York State flags to be flown at half-staff Tuesday in Neutra’s memory.

Neutra, who was 21 when he was killed, grew up on Long Island, and attended Jewish day school and camp. Speakers recalled childhood memories of him: a banana costume he wore in fifth grade, his affection for the Knicks, and his penchant for competing to eat the last slice of pizza.

Alyssa Mendelowitz, who became friends with Neutra in first grade, recalled sitting across from him in a 10-person Hebrew class.

“I did not only want to listen to whatever Omer Neutra had to say, but I wanted to find a way to learn from him and become more like him,” Mendelowitz said. “To me, Omer wasn’t just a classmate or close friend. He was someone that challenged me to want to do more and be better.”

Wearing a jacket that was once Omer’s, his younger brother Daniel lamented that he would soon be older than his brother will ever be.

“I have to grow old without him by my side,” Daniel Neutra said. “At least when I have to explain to my children and grandchildren who Omer was, I will have thousands of interviews, articles and documentaries to reference.”

Hanging over Tuesday’s service was the shadow of that long effort, and the realization that Omer would not be returning to his home an ocean away.

“The truth is that we prayed, and the truth is that we davened, and the truth is that we sounded the shofar to crash the heavens, and the truth is that we lit extra Shabbat candles,” said Midway’s Rabbi Joel Levinson. “And the truth is that we wanted a different end to this story.”

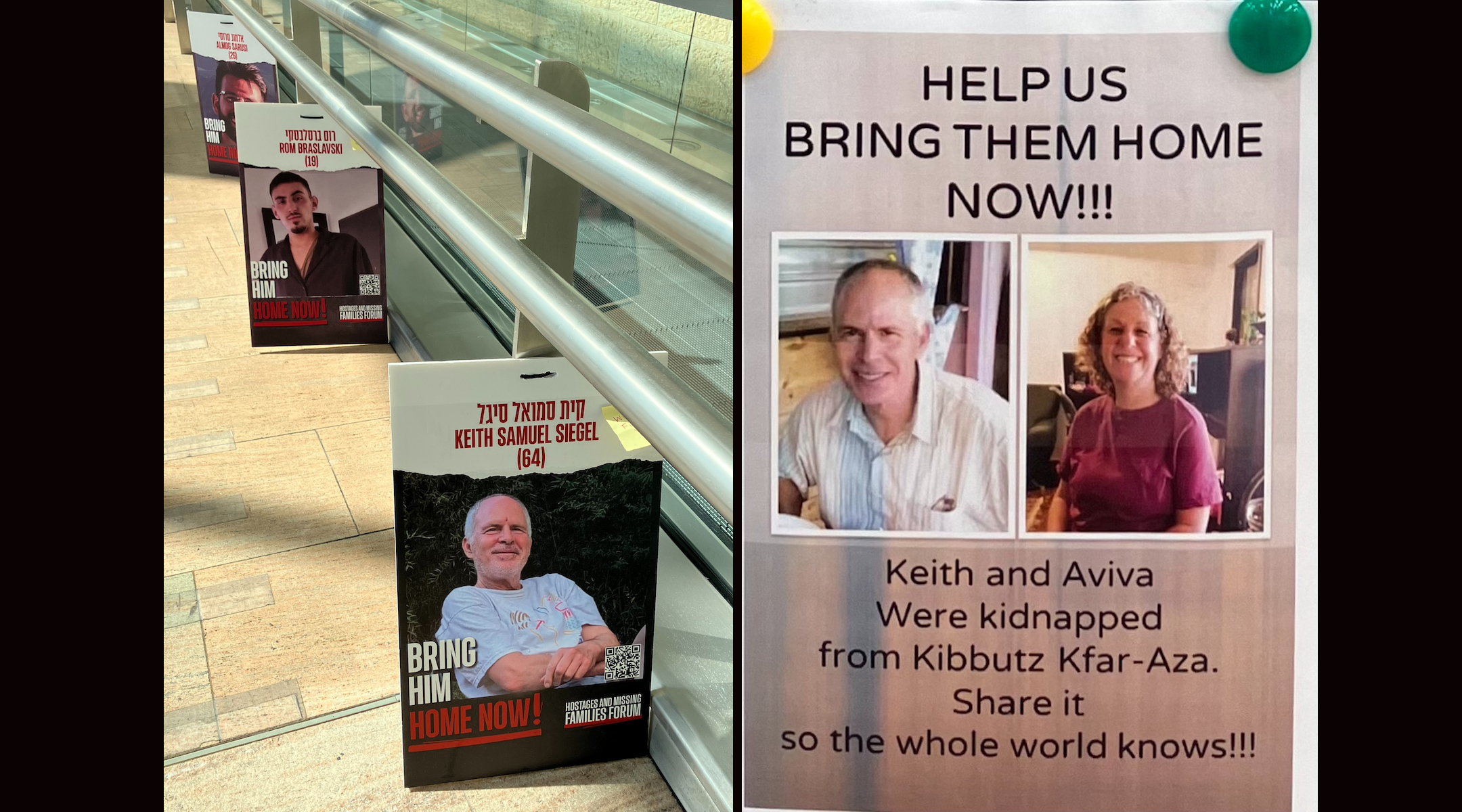

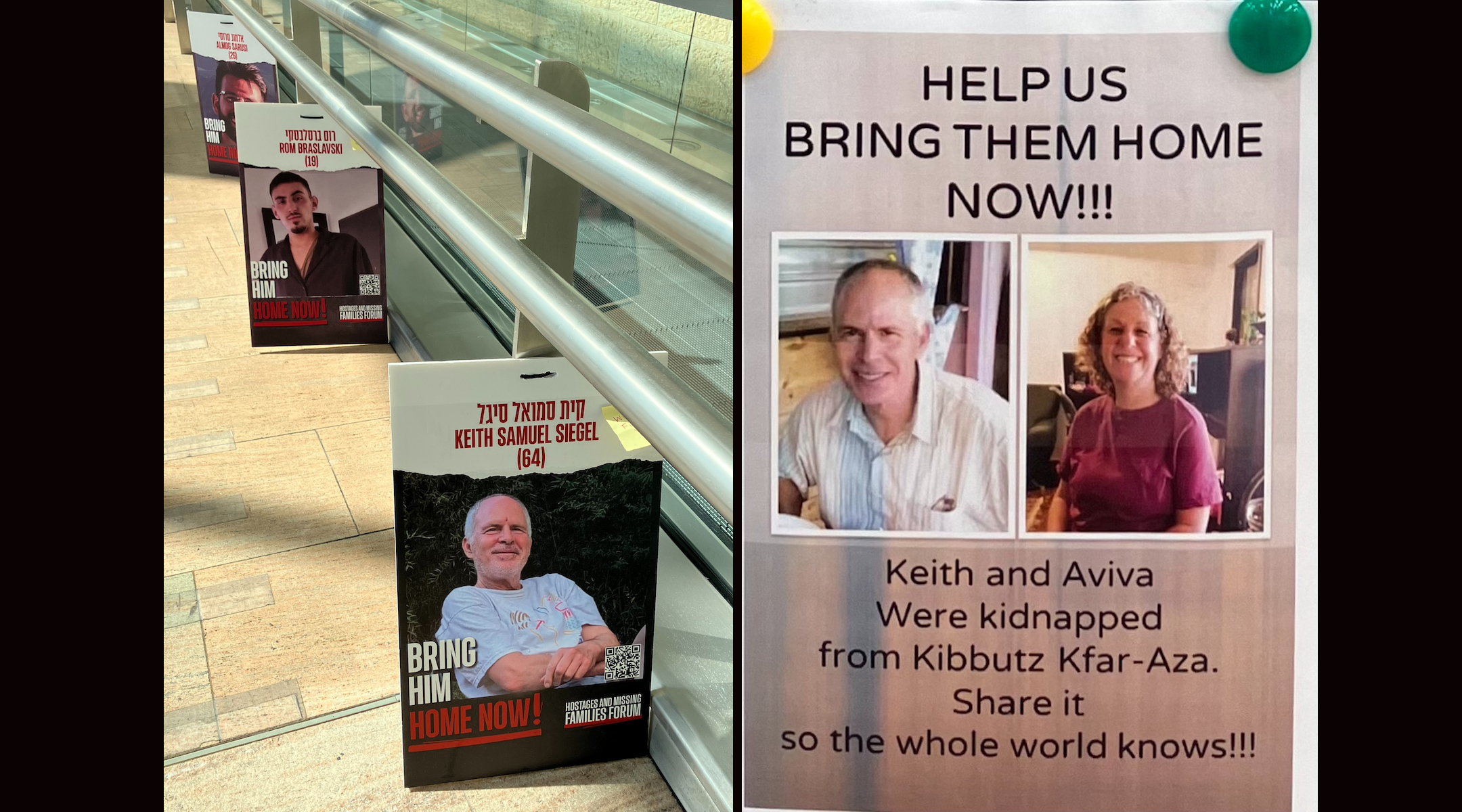

Family of hostage Keith Siegel buries its matriarch, 424 days into his captivity in Gaza

In a different world, Keith Siegel would have joined his siblings at their mother’s bedside as she breathed her last breath on Sunday.

Instead, Gladys Siegel, the family’s matriarch and a pillar of her local Jewish community, slipped away at 97 — unaware that her youngest son had been a hostage of Hamas for 421 days.

The family had shielded Gladys, who had dementia, from the horrifying reality, even as they devoted themselves to advocating for Keith and the rest of the Israeli hostages in Gaza.

“We are thankful that our mother did not have to suffer the pain and suffering of every day that Keith, her youngest child, her baby, has remained a hostage,” Lee Siegel, the oldest of Gladys’ four children, said during her funeral Tuesday at Beth El Synagogue in Durham, North Carolina, where I grew up.

Keith’s wife Aviva, released from captivity a year ago after 51 days, has met President Joe Biden, testified in the Knesset and spoken at rallies on multiple continents. This week, she was in North Carolina, part of the ingathering of the Siegel diaspora as Gladys stopped eating and began to fade.

In a eulogy, Aviva shared a detail from her time in captivity, recalling a moment two weeks into the ordeal when Keith broke the silence their captors had demanded.

“He came up to me and he whispered, and he said, ‘The first thing that I want to do when I get out of here is to go to my mom to give her a hug,’” she shared. “So Gladys, I’m here telling you that from Keith, because he would have loved being here, and it’s just unfair for him not to be here.”

Gladys Ruth Concors was born on July 11, 1927, in Brooklyn. After graduating from Syracuse University, she met and married Earl Siegel, a pediatrician who died in 2001 after more than 50 years of marriage. The couple lived in the San Francisco Bay Area before moving to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 1965, where Gladys became an enthusiastic and devoted booster of the local Jewish community and the Carolina Tar Heels.

In addition to making history as the first woman president of both the Conservative Beth El Synagogue and the Jewish Federation of Durham-Chapel Hill; heading the local chapter of Hadassah, the Jewish women’s organization; and steering Beth El’s 1987 centennial celebration, Gladys Siegel drew attention with her elegant nails — often painted in the signature blue of the University of North Carolina’s vaunted basketball team.

Gladys Siegel, her nails painted Carolina Blue, inscribes a pillar at Beth El Synagogue in Durham, North Carolina, during its renovation in 2018. (Jane Gabin)

During her funeral, Rabbi Daniel Greyber recalled where Gladys would sit each Shabbat, and where she would stand to share the names of any of her loved ones who were in need of healing during the Misheberach prayer for the sick.

“And when there was an injured Tar Heel basketball player, or when [Coach] Roy Williams was having knee surgery, she would proudly and wildly include their names, combining Gladys’ two religious life commitments, Judaism and Carolina basketball,” Greyber recalled.

Gladys Siegel’s generosity to her community was legendary, from the 50 years she spent delivering Meals on Wheels to her habit of visiting the sick to the weekly open-door policy she followed when it came to populating her Shabbat dinner table.

“I always used to talk to and ask her, how many people do you have on Friday for supper? And she said, I don’t know — yet,” Aviva Siegel recalled.

I was one of those guests one of the last times I saw Gladys, when I took my then-infant son to Chapel Hill, my hometown, to let my parents show him off to the community where I grew up. I have no memory of first learning that Gladys was an unparalleled pillar of that community, playing a role even in my very existence — as she sought to set up my mother, then her tenant, with my father more than four decades ago.

This week, I dug out my records from my 2010 wedding to confirm that, yes, Gladys was there, as she was at so many simchas. I also rediscovered something I had forgotten: that her gift to me and my husband was characteristic of her spirit: a donation to Mazon, the Jewish hunger relief organization.

“I don’t know if you guys know about the 50 years of Meals on Wheels that she did … I don’t think she needed to do more than that,” said her grandson Natan Siegel, who lived with his grandmother after moving from Israel to attend UNC.

For her children — Lee, David, Lucy and Keith — Gladys was an unflagging advocate — applying the same zeal, some of them recalled, to their Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts projects, their music lessons and their schoolwork as she did to her civic activities.

“She was solid, steady, supportive and interested in each of her children,” Lucy Siegel said, recalling that her mother turned their basement into a Girl Scout cookie distribution center each year. “She made time for each of us, individually and in connection with our activities.”

Gladys was active and involved well into her 90s. In her final years, she received frequent visits from her children; from her many friends; and from Greyber, who regularly posted selfies from her senior home.

There, her family took pains to ensure that she would never be aware of the tragedy that had befallen her son Keith, at his home in Kibbutz Kfar Aza, and her beloved Israel. Gladys Siegel is survived by four children, 10 grandchildren and 13 great-grandchildren.

A hostage poster showing Keith Siegel can be seen at Israel’s Ben-Gurion Airport. His wife Aviva was freed from Gaza in November 2023. (Jane Gabin)

“Lucy, you were simply a hero, protecting your mom, keeping her from heartbreak, helping her to live out the last days of her life with chocolate in her mouth and peace in her heart,” Greyber said.

The rabbi said he had dreaded Gladys’ funeral, doubting that he could find the right words to match the woman who in many ways built the community he leads.

“I don’t know what a world looks like without my dear Gladys, I don’t know what the future holds for Keith, this precious family, or Israel, or our community. I don’t know, and if I’m honest, it’s pretty scary right now to try and imagine where the light is going to come from,” Greyber said.

“But Gladys taught us, ‘Maalin bakodesh,’ we go up in holiness,” he added. “We have to have the courage to light the candles ourselves, to bring more light into the world, to call and send emails of lovingkindness and connection, to march for hunger and bring and make home-cooked meals, to send hugs, and hugs and more hugs — now that Gladys’ light has gone.”

To that charge, Lee Siegel added another.

“We ask that the Beth El community honor our mother’s memory with renewed and urgent efforts to help us bring Keith and the other hostages home,” he said. “We must continue to believe that with hard work, a better day is coming — as that will always be our mother’s legacy.”

Thessaloniki breaks ground on new Holocaust museum

For half a millennium until the Holocaust, the cosmopolitan city of Thessaloniki, Greece, had a unique claim to fame: it was Europe’s only major city with a Jewish majority.

But the golden age of Thessaloniki’s mostly Sephardic Ladino-speaking Jewish community came to a sudden end with the Nazi occupation of Greece in 1941 and turned cataclysmic with the deportation two years later to Auschwitz of nearly all the city’s Jews. By the end of World War II, some 65,000 Greek Jews — 87% of the total and 96% of those from Thessaloniki — had been killed, leaving barely 2,000 survivors in Thessaloniki (also known as Salonika).

Among them were the parents of Dr. Albert Bourla, a veterinarian who would go on to become the chairman and CEO of Pfizer, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies.

In 2022, Bourla won the Genesis Prize — often described as the Jewish Nobel — for having led the development of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine. Stan Polovets, co-founder and chairman of the Genesis Prize Foundation, said in announcing the reward, “Millions of people are alive and healthy because of what Dr. Bourla and his team at Pfizer have accomplished.”

Now, with global antisemitism at its worst levels since World War II, Bourla is about to realize another milestone: the long-awaited opening of a Holocaust Museum of Greece.

Bourla donated the $1 million Genesis Prize money toward construction of the museum. The museum is also being funded by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, and the governments of Greece and Germany. The management of the museum is currently trying to raise an additional $10 million.

“Those who know me know that in addition to being very proud of my Jewish heritage, I am equally proud of being Greek,” Bourla said in an emotional June 2022 speech in Jerusalem accepting the Genesis Prize. “My mother’s courage and optimism came from her experience of narrowly escaping death at the hands of the Nazis. In fact, both of my parents turned their experience surviving the Holocaust into something positive and life-affirming. This clearly shaped my worldview.”

The 9,000-square-foot museum occupying eight floors in an octagon-shaped structure will be located at the site of Thessaloniki’s Old Railway Station, where the first Nazi train carrying Jews to Auschwitz departed on March 15, 1943.

But the museum, slated to open in 2026, won’t be just about the tragedy of the Holocaust. Exhibits and artifacts will tell the story of more than 2,300 years of Greek Jewish history in Thessaloniki and 38 other communities, beginning with the ancient Romaniote Jews who settled in Greece during the reign of Alexander the Great.

At an Oct. 29 groundbreaking ceremony in Thessaloniki, Polovets was joined by German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou, and local dignitaries and Holocaust survivors.

“I was honored to participate and was moved by the ceremony, during which President Steinmeier said he ‘felt shame’ and that the memory of what was done to the Jewish people on this site ‘cannot be erased.’ That is why this museum is so important,” Polovets said. “The memory of this once-vibrant Greek Jewish community and its near destruction by the Nazis — especially during the current wave of rising global antisemitism — must never be erased.”

Only about 5,000 Jews remain in Greece: About 4,000 live in Athens, and the remainder live in Thessaloniki, Ioannina, Rhodes, Corfu and other communities. Meanwhile, Greece has not been immune to the wave of antisemitism sweeping Europe. Vandalism of Jewish cemeteries and Holocaust memorials is fairly commonplace.

A 2014 global survey of antisemitism by the Anti-Defamation League found that 69% of Greeks harbor antisemitic views — the highest percentage of any country in the world outside the Middle East. While those findings are sometimes disputed, Greece continues to struggle with antisemitism.

However, physical violence against Greek Jews is extremely rare, and the current Greek government, as well as the one that preceded it, are considered among the most pro-Israel in Europe. Greece observes International Holocaust Remembrance Day, and in 2014 the parliament outlawed Holocaust denial.

A big push for the Holocaust museum came from Thessaloniki’s former mayor, 82-year-old Yiannis Boutaris, who died on Nov. 4, less than a week after the Holocaust museum’s groundbreaking ceremony. Boutaris announced that his city would build the museum at a 2017 event attended by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and other dignitaries.

“It will symbolize our shame,” Boutaris said at the time, “for what happened, for what we did, and mostly for what we could not or did not wish to do… during and after the war.”

In addition to Bourla, other famous Jews with roots in Thessaloniki include actor Hank Azaria, Israeli businessman and philanthropist Leon Recanati, his sister the philanthropist Jude Recanati, actress Lea Michele, former Nevada congresswoman Shelley Berkley and Belgian-born American fashion designer Diane von Fürstenberg.

Polovets said Bourla’s donation aligns with the Genesis Prize Foundation’s values and mission of inspiring Jewish pride.

“With the rise of global antisemitism, education will be at the center of the museum’s activities, hosting permanent and temporary exhibitions and archives that will highlight the value of preserving the remembrance of the Holocaust, acceptance and respect for diversity, human rights, and freedom,” he said.

Polovets said he hopes the museum will inspire visitors to fight hatred from spreading today.

“Hatred in any form leads to denial, disrespect and destruction,” he said. “Democracy and respect for others are values that can never be taken for granted, and each of us has a responsibility to stand up to all forms of hatred.”

Suspect in October hate crime shooting of Orthodox man found dead in Chicago jail

The man accused of shooting a Jew on his way to synagogue in Chicago in late October has been found dead in his jail cell.

Sidi Mohamed Abdallahi, 22, had been arrested and charged with terrorism and hate crime charges for shooting the Orthodox man in Chicago’s West Rogers Park neighborhood on Oct. 26, a Shabbat morning.

Abdallahi, an immigrant from Mauritania, had subsequently exchanged fire with law enforcement when police and paramedics arrived on the scene, and was taken to a local hospital after sustaining a gunshot wound.

Abdallahi was initially charged with 14 total felony counts — including attempted first-degree murder and aggravated discharge of a firearm toward a police officer. But the shooting unleashed a firestorm in Chicago, where the initial lack of hate crime charges drew sharp criticism from local Jewish leaders. Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson also faced backlash for omitting mention of the victim’s Jewish identity in his response to the shooting.

Days later, amid the blowback, hate crime charges were filed against Abdallahi.

At a detention hearing on Nov. 22, prosecutors presented evidence showing that Abdallahi had mapped several Chicago synagogues and Jewish day schools in the days prior to the shooting, including a synagogue one block from the scene of the attack, according to the Chicago Sun-Times.

Abdallahi was found dead Saturday, Nov. 30 at 3:30 p.m. during a routine security check at the health center in Cook County Jail. He was found unresponsive in an “apparent suicide attempt by hanging” in his cell, the Cook County Sheriff’s Office said. He was then taken to Mount Sinai Hospital, where he died.

The Illinois State Police Public Integrity Task Force is conducting an investigation, according to the sheriff’s office, which said there was no sign of foul play and that Abdallahi was not considered a suicide risk. An autopsy is also being conducted, according to a local ABC affiliate.

“My community has been on edge for quite some time,” Alderwoman Debra Silverstein, herself an Orthodox Jew who represents West Rogers Park, told the Sun-Times. “I hope this will bring a small measure of closure.”

Silverstein, who had expressed outrage at the initial lack of hate crime charges, also said she hoped the investigation would continue. “We would still like to find out all the details about what happened,” she said.

‘Words alone have no power to comfort’: Family of hostage Omer Neutra, killed by Hamas, calls for deal to save living captives

For months, the family of Omer Neutra has called, in speech after speech, for a deal that would free him and the other Israeli hostages held in Gaza.

Now, in their first statement following the announcement that Neutra died in Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, attack, his parents and brother are repeating that call. They said the past 423 days, before they found out he had been killed, had been harrowing, and appealed to President Joe Biden and President-elect Donald Trump to bring about the release of the remaining hostages.

“It was an unimaginable nightmare to be acting based on the hope that he was alive, despite having little information or signs of life since he was seen on video being taken on October 7th,” Ronen and Orna Neutra, his parents, and Daniel, his brother, said in a statement on Monday, following the Israeli military’s announcement of his death. Neutra, an Israeli tank commander, was killed in battle during the Oct. 7 attack.

“In the 423 days since October 7th, we expected our leaders to demonstrate the same courage displayed so bravely by Omer and rise to the occasion on behalf of those who were killed and kidnapped, just as our beloved Omer showed until the very end,” continued the statement from the family, who live in Long Island. “While we appreciate the support we have received from so many in our community, in New York, in Israel and across the world, the feeling today is very difficult. The grief is heavy”

The Neutras have been among the most prominent families advocating for the hostages’ release, and spoke at the Republican National Convention in July. Their statement Monday included an appeal for leadership, both to the outgoing president and the incoming one.

“Sadly, time has run out to bring Omer home alive and words alone have no power to comfort,” the statement said. “Leadership will only be revealed in actions and results going forward. We call upon the Israeli government to work with President Biden and President-elect Trump, to use all of their leverage and resources to return all 101 hostages — living and the deceased — to their families as soon as possible.”

Following the news of Neutra’s killing, Trump said there would be “all hell to pay in the Middle East” if the hostages are not released by his Jan. 20 inauguration. Biden said he was “devastated and outraged” by Neutra’s killing and pledged, “I will not stop working to bring your loved ones back home where they belong.”

A memorial service for Neutra will be held on Tuesday. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has ordered flags on state buildings to be flown at half-staff on that day.

Andorra, where non-Catholic houses of worship are illegal, gets its first full-time rabbi

The last few years have brought a string of Jewish milestones for Andorra, a tiny, landlocked microstate in the Pyrenees where non-Catholic houses of worship are prohibited by law.

Last year, a Jewish lawmaker joined the legislature for the first time. And this summer, the lawmaker’s brother told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that the local Jewish community was negotiating with the government to secure land for a cemetery.

Now, Andorra has gotten its first-ever full-time rabbi — a Chabad emissary named Kuty Kalmenson.

The Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement announced Kalmenson’s appointment on Sunday at its annual conference for emissaries in Brooklyn, called the Kinus, which drew 6,500 rabbis who are stationed in more than 100 countries. It said in a news story that he and his family — his wife Rochel and their five children — had until recently been living in Ningbo, China, a city of more than 9 million south of Shanghai, but left because there were no longer Jews living or visiting there.

Their arrival last month increased the number of Jews living in Andorra by perhaps 10%. Locals this summer told JTA that the official Jewish community, which operates a cultural center in an underground office building to sidestep the prohibition on synagogues, had 73 members.

Kalmenson, who will take over leadership at the cultural center, told Chabad.org that he believed the actual number of Jews living in Andorra to be substantially higher — perhaps 250 among a total population of around 80,000.

In addition to helping locals obtain kosher food, receive Jewish education and fulfill other commandments under Jewish law, Kalmenson’s duties will include serving Jewish travelers who visit the principality, which officially has two heads of state: the French president and the Catholic bishop of Urgell, in the Spanish region of Catalonia. Last year, roughly 10 million people visited Andorra, drawn by its luxury duty-free shopping and ski resorts.

“We hope to bring everyone together — the veteran community members and those who’ve never been involved in Jewish life before,” Kalmenson told Chabad.org.