WASHINGTON (JTA) – Add sweeping school reforms – and with them, funding for private schools that Orthodox groups embrace and secular Jewish groups fear — to the campaign promises that Donald Trump plans to fulfill.

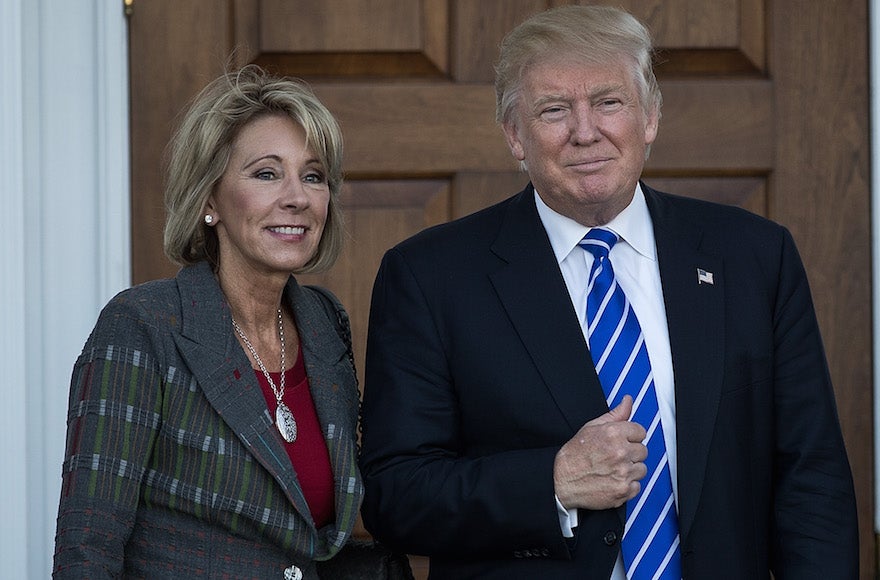

Last week, just before Thanksgiving, the president-elect named Betsy DeVos, a billionaire education reform activist and champion of charter schools and public funding for private schooling, as his education secretary.

As leader of the American Federation for Children, a group that promotes charter schools, DeVos promotes exactly the model advanced by Trump’s son, Donald Trump Jr., at the Republican convention in July. The elder Trump has said he would earmark $20 billion in federal money to charter more independent schools or for vouchers for poorer families to pay for private schools. By picking DeVos, whose advocacy and funding for lobbying has led to sweeping changes in her home state of Michigan and elsewhere in how schools are funded, he seems to be moving in that direction.

“Under her leadership, we will reform the U.S. education system and break the bureaucracy that is holding our children back so that we can deliver world-class education and school choice to all families,” Trump said Nov. 23 in announcing the DeVos nomination.

“School choice” is music to the ears of Orthodox Jewish groups, sometimes joined by other proponents of Jewish day schooling, who have argued for decades that constitutional church-state separations should not cut off day schools from public funds. Jewish day school tuition can cost $14,000 a year, and at least twice that for Jewish high schools, especially in the New York area.

Agudath Israel of America, welcoming the announcement, said it has worked with DeVos for years “to give parents educational options for their children.”

Opponents of the broader choice DeVos favors have illustrated flaws in the Michigan model to make the case for the public school system and its regulatory oversight. Michigan’s national ranking has dropped commensurate with the expansion of charter schools as a result, in part, due to her advocacy, critics point out.

Nathan Diament, the Washington director of the Orthodox Union, called the DeVos nomination “encouraging.” He said that parental oversight would act as a corrective once parents have a broader range of school choice.

“The regulators of the schools should be the parents, the parents who care for their children,” Diament said. “They’ll see if the school is making a good education and if it’s not, they will move their child to another school.”

Jewish groups that advocate for stronger church-state separations, including the Anti-Defamation League and the Reform movement, were silent on the DeVos pick, declining JTA requests for comment. That’s not in itself unusual, as Jewish nonprofits generally observe the “if you have nothing nice to say, say nothing at all” rule when it comes to presidential personnel choices.

General church-state separationists were less circumspect.

Americans United for Separation of Church and State called the DeVos nomination an “insult to public education.”

“Private school vouchers violate the fundamental principle of religious freedom because they fund religious education with taxpayer dollars,” it said in a statement.

Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers and heir to a long tradition of Jewish advocacy in and for public education, said the DeVos appointment is “about the decimation of a public school system for children.”

“I’m not surprised those who want vouchers are celebrating this choice,” Weingarten said in an interview.

She said the inequities that Orthodox Jews say are embedded in restrictions on public funding for religious education — high taxes for services they don’t or can’t use — are better addressed through government paying for nonsectarian activities and needs.

“We found ways to spend public dollars for remedial education, for transportation, for special needs” for Orthodox Jewish day schools, Weingarten said. “We found ways to ensure that people who had reason to want religious education and yet at the same time … were entitled to public dollars, to get them.”

In recent years there has been a softening of opposition among non-Orthodox groups to government-funding ideas for parochial schools, as the cost of day schooling has soared and its benefits in building Jewish identity are seen as incalculable. Jewish federations have been active in efforts to obtain state money for things like technology and textbooks, while some Jewish groups are supporting state programs that provide tax credits for donations to private schools.

Nevertheless, in May, the Jewish Council for Public Affairs, representing a network of local Jewish community relations councils and national agencies, reiterated in a policy compendium that it “opposes policies that divert resources from public schools, such as voucher programs that provide public dollars to non-public schools, whether secular or sectarian; we strongly support private funding for Jewish day school education.” The Orthodox Union dissented.

Fears of sweeping changes may be overstated. Democrats, while in the minority in the Senate, are still able to filibuster laws, and much of the education system is run at the state and local level.

Diament said he saw the DeVos choice as one of setting a tone encouraging broader school choice through advocacy and federal funding incentives.

“Even without legislation, first of all, from the bully pulpit, she can be an advocate to the states and local government agencies to do more in terms of school choice,” he said.

Marc Stern, general counsel for the American Jewish Committee, said the changes that DeVos hoped to achieve would face a number of practical hurdles. The expansion of the use of vouchers for private schools, for instance, would invite greater government scrutiny, he said.

That could meet resistance among the haredi Orthodox, whose schools emphasize religious studies over secular studies. Last year, the New York City Department of Education launched an investigation of three dozen yeshivas suspected of failing to meet standards in secular subjects such as English, math and science.

“It may have some implications for the Hasidic community, where accountability has been a hot-button issue in recent years,” Stern said.

Church-state separationists would also likely seek to enforce anti-discrimination laws on schools benefiting from vouchers, Stern said, leading to battles over whether schools must hire staff or admit students whose families deviate from conservative moral codes.

“What if you have to admit children of gay marriages?” he asked.

Stern said a Trump administration could learn, as it facilitates public spending for private schools, that not all comers would be to its ideological liking – but there would be little the administration could do to discriminate.

“Who’s to prevent Farrakhan from applying” for public funds for schools, he said, referring to the leader of the radical anti-Semitic Nation of Islam movement.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.