(JTA) — He demanded civil rights by invoking the Hebrew Bible, just one of the many reasons the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. drew praise, admiration and followers among American Jews in the 1960s. And when he was gunned down in Memphis, Tennessee, by an assassin on this date in 1968, JTA reported on the “profound grief” of virtually every national Jewish organization — and on incidents that foretold the deterioration of black-Jewish relations in the decades to come.

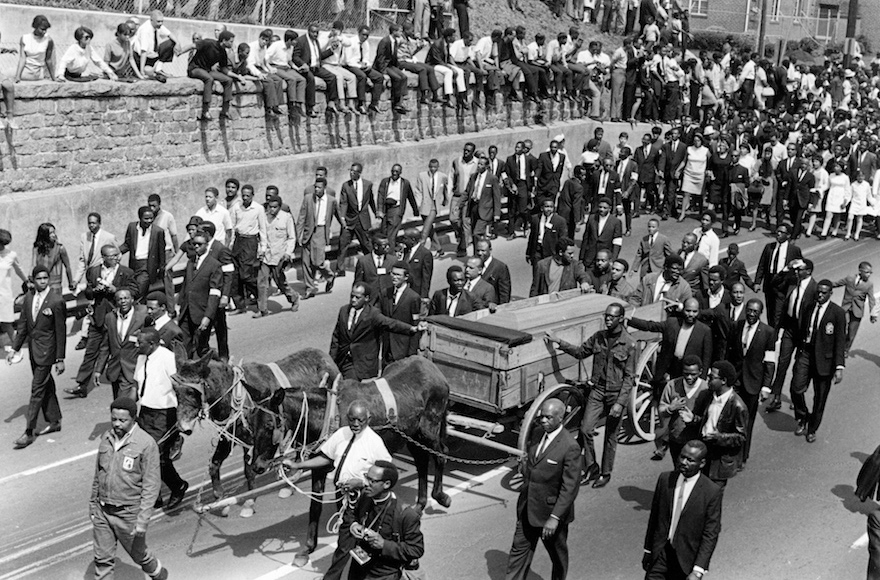

On April 8, four days after the assassination, JTA reported on a memorial march for King. “Scores” of Jewish leaders took part, and the grand rabbi of France, Jacob Kaplan, sent a telegram of condolence to King’s widow, Coretta Scott King.

That same today, the Washington Hebrew Congregation held a memorial for King where Rabbi Richard Hirsch, head of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, described the late civil rights leader as “the righteous man of our generation” and “the most American of Americans.”

Israelis, too, were touched by King’s legacy and mortified by his assassination. Israel’s president, Zalman Shazar, sent condolences to Mrs. King, JTA reported, and Foreign Minister Abba Eban called the slain leader “an historic figure in the struggle for freedom and equality” whose work “will live long after him.”

On Tuesday, April 9, the day of King’s funeral, the Jewish Education Committee of New York said that more than 700 Jewish schools in the New York metropolitan area, attended by some 150,000 pupils, were closed as a sign of respect, as were the offices of many national and local Jewish organizations.

Jewish groups also mixed mourning with calls to action.

Leaders of Operation Connection, an interreligious coalition that included the American Jewish Committee, urged Congress to pass legislation that “adequately meets the needs for jobs, housing, health and poverty funds and eliminates crippling social welfare amendments.”

On April 10, the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council — a precursor to today’s Jewish Council for Public Affairs, representing the country’s community policy organizations — called on President Lyndon Johnson and Congress to launch a comprehensive federal program to “banish inequality, injustice and poverty,” saying its members were prepared “willingly to assume whatever share may fall upon us” of the economic costs entailed.

A resolution called for a program that would provide “a decent job for all who are employable or can be made so by retraining; income sufficient to provide all others with essentials of civilized living; decent dwellings for all; medical care for all; education to the limits of each person’s capacity, and the elimination of all forms of discrimination and segregation from the life of our society.”

The resolution also denounced the “rioting, pillaging and looting” in major cities that followed in the wake of the assassination, but noted that the factors that led to the violence “lie deep in the long history of enslavement, oppression, denial, segregation and discrimination to which Negroes have been subjected in our society.”

The deliberations over the resolution also reflected another consequence of that violence: “the Jewish merchants who were among the victims of the disorders that followed the King assassination.” Community relations councils in cities where the riots occurred were urged to develop “special approaches for counseling and for practical assistance to these victims.”

A week later, on April 15, JTA reported on a survey by The Kansas City Jewish Chronicle showing that “Jewish merchants and property owners suffered some of the heaviest losses in the two days of rioting, arson and looting that shook Kansas City” following King’s assassination. “Many stores that were destroyed or looted were owned by Jews, and some merchants said they were completely wiped out and are unable or unwilling to re-open their businesses,” according to the report.

JTA would go on that spring to report on relief funds being set up for Jewish merchants in Baltimore and Pittsburgh. The urban unrest that erupted after King’s killing — or that flared the year before, during the “long hot summer” of 1967 — severed a long and often uneasy relationship between Jews and blacks living in the inner city. It accelerated the “white flight” that saw the last remnants of the many historic urban Jewish communities relocate to the suburbs.

That December, JTA would report on the 37th General Assembly of the Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds — today’s Jewish Federations of North America. Among the challenges of “crisis proportions” facing the Jewish community, delegates agreed, were threats to the survival of the State of Israel, the education of “alienated or indifferent” Jewish youth, and this: “American cities, where racial conflicts and growing Negro anti-Semitism is testing Jewish resolve to participate in the struggle for civil rights.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.