BARTAA, Israel (JTA) – The line in this bifurcated Arab village where Israeli sovereignty ends and the Palestinian Authority’s jurisdiction begins isn’t marked by a sign, fence or checkpoint.

There’s just a dry, trash-strewn riverbed and a traffic-choked roundabout filled with cars trying to maneuver through throngs of shoppers.

Yet the invisible boundary that separates western Bartaa, which is part of Israel, from eastern Bartaa, which is in the West Bank and under Palestinian jurisdiction, holds a great deal of consequence.

Those who come from the western side of the line are Israeli citizens. They carry Israeli identity cards, can travel and live anywhere in Israel, and may vote in Israeli elections. Those who come from the Palestinian side have none of those rights.

Day to day, residents cross the unseen line without a second thought. But over the past few months, it has created another disparity: Only those from the Israeli side can get COVID vaccinations at will. Israel has vaccines in abundant supply, but by and large has not given them to Palestinians.

So when Israel launched a temporary vaccination site here starting in January to make it easier for Bartaa’s residents to be vaccinated locally by opening the site for an afternoon every week or two, the color of one’s identity card made all the difference.

A man receives his second vaccine dose at a temporary vaccination site in Bartaa. (Uriel Heilman)

A man receives his second vaccine dose at a temporary vaccination site in Bartaa. (Uriel Heilman)

Those with Israeli identity cards, which are blue, were quickly processed and got their shot. Those with Palestinian identity cards, which are green, were technically not eligible to be vaccinated. Nor were Palestinians who hold Jordanian passports – a group that comprised a large proportion of the Palestinians at the site.

“Generally, people with green identity cards can’t get the vaccine,” said Kaisar Kabha, director of Israel’s Basma regional council, which includes Bartaa and two other nearby Israeli-Arab towns. “But in Bartaa that doesn’t make sense because people from all over the West Bank come to the business district on the Israeli side. If you have a Palestinian grocer who interacts with Israelis, you also have to protect him so he won’t infect others.”

Within the confines of Bartaa, a village of 15,000 in north-central Israel, the distinctions between Israelis and Palestinians are difficult to discern. An informal agreement allows both nationalities to move about freely on both sides. Plenty of Israeli Bartaa residents live on the Palestinian side of the city because their spouse is Palestinian, and vice versa. Every morning, scores of children from Palestinian Bartaa travel to school in Israeli Bartaa because they hold Israeli citizenship, even though they reside on the Palestinian side.

Israelis of all backgrounds flock here on weekends to bargain hunt in the countless auto accessory stores, furniture outlets, pet stores and supermarkets on both sides of the line. Palestinians cross into the Israeli side to run businesses, visit family or just grab lunch.

Yet the Palestinians who live here are not allowed to travel anywhere else in Israel, and they’re practically cut off from the rest of the West Bank, too, because the West Bank security fence lies a couple of miles east of this uniquely divided town. To leave Bartaa and travel into the rest of the West Bank, they must cross through an Israeli military checkpoint or sneak through one of the many holes that have turned the security fence into Swiss cheese.

Although most Palestinians don’t technically qualify for Israeli vaccines, the lines also have blurred at Bartaa’s immunization site, which sits squarely on the Israeli side of the city. Abed Tabaha, a Palestinian from the West Bank side of Bartaa, said many of his compatriots were able to be vaccinated at the site despite not holding Israeli citizenship.

“When they first opened this site, they were only giving vaccines to Palestinians with Jordanian passports, but afterward they took those of us with Palestinian identity cards without a problem,” Tabaha said. “We’re getting vaccinated.”

As Israel’s vaccination rates have skyrocketed, Palestinian access to vaccines has become a matter of controversy. Israel has vaccinated some 120,000 Palestinian laborers from the West Bank who have permits to enter Israel, inoculating them at military checkpoints using the Moderna vaccine, while Israeli citizens have gotten the Pfizer vaccine.

But Israel thus far has refused to offer its vaccine stockpile to Palestinians more broadly in the West Bank and Gaza. Critics say the Israeli government bears responsibility for the Palestinians as the occupying power. Israel argues that responsibility for inoculating Palestinians rests with the Palestinian Authority, whose vaccination campaign has been proceeding slowly.

Israel allowed some Palestinians with Israelis in their immediate families to get the vaccine under “family unity” considerations, according to Kabha, the municipal official. He also said that when there were extra vaccines at the Bartaa site at the end of the day, the limits on who could receive them were relaxed.

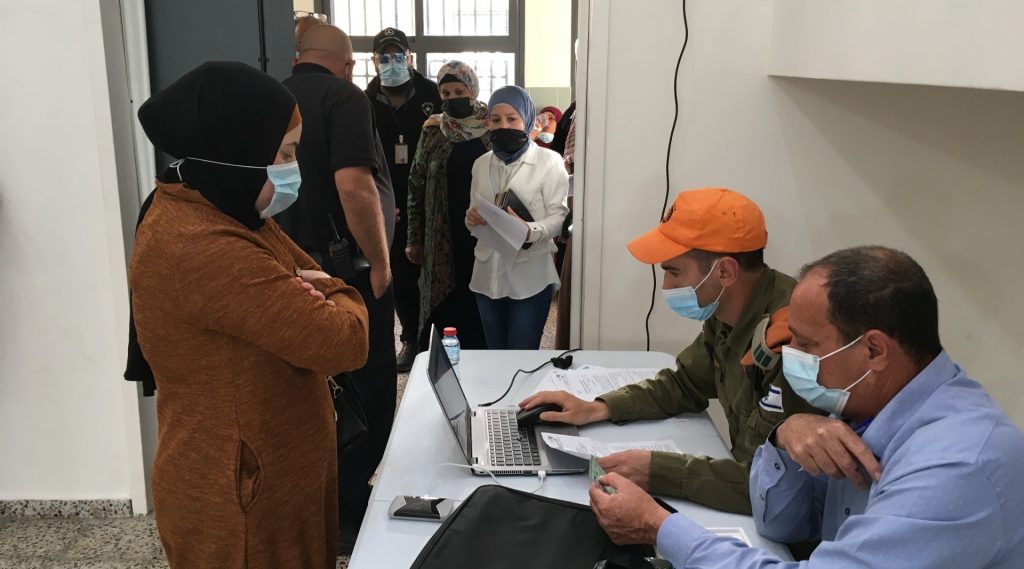

Roi Wolf, at computer, a sergeant in the Israeli army, processes would-be vaccination recipients while Kaisar Kabha, director of the Basma regional council, checks their identity documents. (Uriel Heilman)

“This is the only place I know of where the Israeli Defense Forces’ Home Front Command gave us a certain amount for Palestinians,” Kabha said. (An IDF spokeswoman referred questions about vaccine implementation to the Israeli Health Ministry, which is officially responsible for the site.)

On one recent Thursday afternoon, it wasn’t clear what policy dictated vaccinations at the site, nor who exactly was in charge.

Formally the site is under the aegis of the Health Ministry, which has established temporary vaccination sites in places like this one where, as in many Arab-Israeli municipalities, vaccination rates lag behind the Israeli average. But no Health Ministry officials had come to Bartaa that day; the actual inoculation work was outsourced to a private company to operate the Bartaa vaccination site. On this particular day, the company had sent two staffers to run things.

The real authority at the site appeared to be one of the three unarmed IDF reservists on hand to supervise the operation and keep the peace. A sergeant from Jerusalem named Roi Wolf quickly took charge when the crowd began to grow unruly after it became apparent there weren’t enough shots to go around. The company administering the vaccine sent 120 doses instead of 180, and the two staffers giving the shots appeared feckless and overwhelmed.

“You, go vaccinate,” Wolf barked at one of the staffers sitting at a computer. “I’m taking over. Go work. Yalla, yalla!”

Wolf has been coming to Bartaa frequently over the past year as part of his reserve duty.

“The pandemic doesn’t stop at any border, and we’re making an effort to vaccinate as many people as we can,” he said.

At a coronavirus vaccination site in Bartaa, Palestinians wait alongside Israeli citizens in the hopes of receiving one of an insufficient number of vaccine doses, April 8, 2021. (Uriel Heilman)

Another IDF reservist at the vaccination site, Avner Azulai, 33, wore his kippah as he mingled with the crowd. An events producer from the Haifa area, Azulai said he is proud to represent Israel in its campaign to quash COVID.

“There’s not much difference between Jews and Arabs when it comes to this pandemic,” he said. “Everybody cooperates, even people whom you never imagined would cooperate. This is a situation that unites everybody.

“In Bartaa, the respect and hospitality we’ve gotten exceeds that of any other village. People come to you with open arms. They invite you to their homes.”

Azulai and the other Israeli soldiers here are forbidden from crossing into the Palestinian side of Bartaa. But the invisible border doesn’t stop ordinary Israelis.

On one main thoroughfare on the Palestinian side on a recent afternoon, a kippah-clad Jew with ritual fringes dangling from beneath his shirt chats with a local carpenter. Many store signs on the Palestinian side bear Hebrew writing, and most of the Palestinians speak Hebrew and seem happy to cater to Israeli customers. Because the businesses on the Palestinian side are not subject to Israel’s 17% value added tax, prices tend to be relatively cheap. And in this all-cash economy, prices are negotiable.

At the vaccination site, there’s plenty of haggling, too — mostly to get inside. With the virus still running rampant in the West Bank — the seven-day average COVID-19 case rate is nearly 1,600 among some 3 million Palestinians, compared to under 130 among 9 million Israelis — demand for vaccines is strong at what may be the only Israeli vaccination site that many West Bank Palestinians can access.

A small traffic circle is situated on the boundary between Israeli Bartaa and Palestinian Bartaa. (Uriel Heilman)

Raed Hamarshe, 25, from the nearby Palestinian metropolis of Jenin, said he would have gone anywhere just to get the shot — and got it in Bartaa. While there are some COVID-19 vaccines available in Jenin, he said, the wait is very long. Hamarshe isn’t an Israeli citizen, but he owns a household goods store in Bartaa and has permission to cross the checkpoint.

“I heard they had the shot here, so I came and asked,” he said. “They said yes, and I said thank you.”

Salah Zedat, 54, came to Bartaa from the Palestinian city of Ramallah in the West Bank. He said he wanted a vaccine not so much because he’s afraid of the virus, but because he believes that soon the Israeli authorities won’t let unvaccinated Palestinians cross the military checkpoints.

“I told my friends that in Bartaa they’re giving shots,” Zedat said. “I have two kids who don’t have permission to enter Israel. I can’t bring them here because if they’re caught by the police they’ll be in real trouble.”

Ultimately, he said, it’s in Israel’s own self-interest to make the vaccine more widely available, and it’s the right thing to do.

“I ask every person with a brain not to differentiate between Israeli and Palestinian because the sickness can come to anybody,” Zedat said. “The government needs to realize this, not just the health workers. At the end of the day we’re all people. There’s no difference between a Jew or an Arab, a Christian or a Muslim.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.