Sign up now to attend JTA’s event with translator Jessica Cohen on May 20 at 6 p.m. ET online.

(J. Jewish News of Northern California via JTA) — Anyone who has read any books or essays by contemporary Israeli writers has probably encountered the words of Jessica Cohen.

That’s because Cohen is the most in-demand Hebrew-to-English translator working today. In the past year alone, four of her translations have been published: “Professor Schiff’s Guilt,” a novel by Agur Schiff; “Stockholm: A Novel,” by Noa Yedlin; “Every Wrinkle Has a Story,” a children’s book by David Grossman; and “The Hebrew Teacher,” a collection of novellas by Maya Arad. Cohen also translated Grossman’s op-ed on the Israel-Hamas war, titled “Israel is Falling Into an Abyss,” that was published in the New York Times in March.

Over the past 25 years, she has translated more than 30 books and dozens of shorter works by some of the most renowned Israeli writers, including Amos Oz, Etgar Keret, Dorit Rabinyan, Ronit Matalon and Nir Baram. In 2017, she shared the Man Booker International Prize with Grossman for “A Horse Walks Into a Bar,” and four years later, she was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship.

How did Cohen, whose website is thehebrewtranslator.com, become the go-to translator for Israeli literature?

“I think it’s a combination of good connections and luck,” she said in a recent Zoom interview from Denver, where she has lived since 2008.

Another key factor: She is completely bilingual in Hebrew and English.

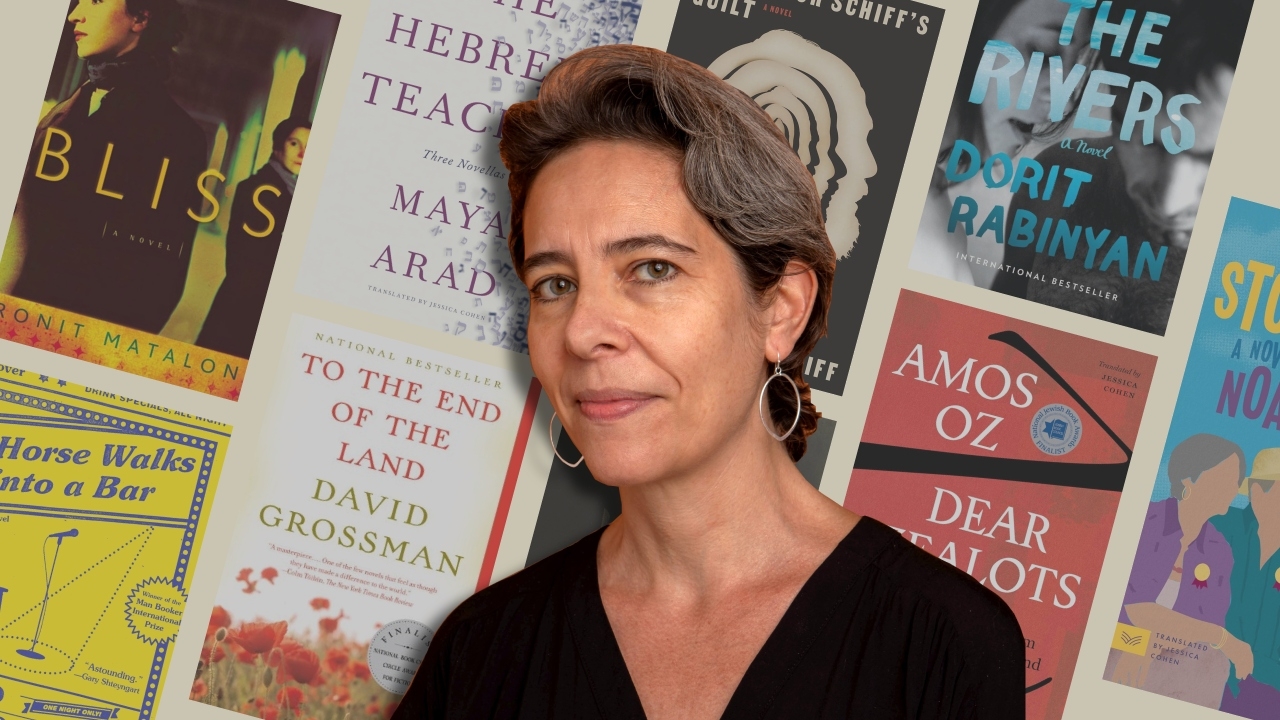

Hebrew translator Jessica Cohen, left, brought her friend and writer Maya Arad’s writing to English-language audiences for the first time in 2024. (Courtesy Cohen)

“Many translators are not bilingual, and it’s certainly not a requirement. But for me, I do feel like it’s very helpful,” she said. “I have both a pretty deep and instinctive understanding of the source language and culture, and I’m translating into my native language.”

Cohen, 51, was born in England and immigrated to Israel with her parents when she was 7. She learned Hebrew at school while continuing to speak and read books in English at home. She studied English literature at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and upon graduating in 1997 moved to the United States with her American-born boyfriend.

“Like so many Israelis, we came intending to stay here for a few years and go back, and 27 years later here, here we still are,” she said. She would go on to marry that boyfriend; they are now divorced and co-parenting their teenage daughter.

Cohen found work doing commercial translation and took up literary translation as a hobby. “I was reading things coming out of Israel that I enjoyed and wished they were in English,” she said. “I thought, well, maybe I could write them in English.”

Meanwhile, she pursued a master’s degree in Near Eastern languages and culture at Indiana University in Bloomington. There, she met Breon Mitchell, a German translator of works by Franz Kafka and Gunter Grass, among others.

Mitchell mentored Cohen and published her first translations — poems by Yehonatan Geffen — in 2000 in a now-defunct journal called Beacons. “I feel privileged to have been present at the earliest stages of Jessica Cohen’s career,” Mitchell said in an email. “I still remember our weekly sessions, discussing her drafts of those poems. They remain among my fondest memories.”

Eager for more work, Cohen contacted Deborah Harris, the literary agent who represents some of Israel’s top writers abroad. Harris liked Cohen’s samples and set her up to translate “Bliss,” an edgy novel about an Israeli woman who has an affair with a Palestinian man by the late Ronit Matalon.

“She was one of Israel’s most critically acclaimed and interesting writers, and in retrospect it was an incredibly difficult book to translate as my first experience,” Cohen said. The translation came out in 2003 and led to an invitation to translate “Her Body Knows” by Grossman, a literary superstar in Israel who is also represented by Harris.

“That was the biggest door-opener for me, and I’ve translated all his work since,” Cohen said, including “To the End of the Land,” his bestselling 2008 novel that was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award.

There are only a half dozen professional Hebrew-to-English literary translators, Cohen said. Arad, who is close with Cohen, said by email that Cohen’s unique skill set distinguishes her from other translators with whom Arad has worked.

In addition to being bilingual, “she has a super sensitive ear for the texts she translates, and she strives to find the right English words and the right register for each book,” Arad said. She also “makes sure every tiny detail is right until the text is perfect.”

For a typical book project, Cohen produces at least three drafts. The first is very rough. While working on the second, she jots down questions about vocabulary or style to send to the author by email. Then she does another round or two of polishing.

“Some writers like to be very, very involved and will really read the entire thing and comment on it,” she said. “Most don’t because they either don’t have the time, or their English isn’t good enough, or they’ve moved on to other things, or they trust me.”

Cohen’s translations often become the urtexts for translations of Israeli books into other languages, rather the original Hebrew versions, she said.

She is currently working on Arad’s “Happy New Years,” which was a hit when it came out in Israel last year. She is also plugging away at Lea Aini’s 2009 novel “Rose of Lebanon.” “It’s one of the best works of Hebrew literature to my mind,” she said.

Is there any kind of book she would decline to translate?

“I would say that I know my strengths, and poetry is not one of them,” she said. “Most poetry translators are poets themselves. I’m not a poet. It’s just not the way my mind works.”

And don’t get her started on the expression “lost in translation.”

“People just inherently assume that a translation is inferior to the original, and I don’t like that assumption,” she said. “A translation is never going to be the same as the original. It’s different, by definition. And there are things that can be gained in a translation. Sometimes there are fortuitous parts of a text that in the translation can gain a whole different level of meaning.”

In addition to her translating work, Cohen advocates for the rights of translators as a member of the Authors Guild. She helped conduct a 2022 survey of literary translators that found that 63.5% of respondents made less than $10,000 per year from translating work and that only 11.5% earned 100% of their income from such work.

“One component of the work that my colleagues and I do is to try to make more translators aware of their rights,” she said. “Pay is obviously the big thing, but there are other issues, like getting royalties and getting proper credit, including having the translators’ names on the cover.”

Despite living in the United States for more than two decades, Cohen said she doesn’t really feel at home here. She grew up in a “very, very secular” family and is not involved in the Denver Jewish community. She stays connected to Israel by reading Haaretz every day and listening to Israeli radio.

“I never have enough time to read everything I would like to, but people send me a lot of books to read that they would like me to translate,” she said. “I try to stay on top of the important things coming out.”

Cohen said she was rattled by the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks and their aftermath. In 2017, she donated half of her Booker Prize winnings to the Jerusalem-based nonprofit B’Tselem, which documents human rights violations against Palestinians living in the West Bank. She said the situation now is “so much worse now than in 2017” and called the current war between Israel and Hamas “very dispiriting and horrifying.” (It has also ensnared another prominent Israeli translator, Joanna Chen, whose coexistence essay drew criticism and then was retracted by a literary magazine.)

Cohen believes that Americans, including American Jews, do not read enough books in translation. They can’t possibly understand the complex Israeli story, she said, if they ignore books by Israeli authors.

“I think a lot of people do not have a really full multidimensional understanding of what that country and what that society is,” she said, “and one of the ways to get that bigger picture is through reading.”

This story originally appeared in J. Jewish News of Northern California and is republished with permission.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.