When I think of my friend and spiritual advisor Andy Sacks, I think of the words of the late civil rights icon, Rep. John Lewis, who urged his followers to “get into good trouble.”

As the longtime director of the Rabbinical Assembly in Israel, Rabbi Sacks headed the Conservative movement’s Bureau for Religious Affairs. In more than 28 years in that role he fought tirelessly for the right of non-Orthodox rabbis and congregations in Israel to operate on a level playing field with Israel’s state-supported Orthodox rabbinate.

Sacks, 70, who died June 28 after battling cancer for several years, was an activist for religious pluralism, emerging as one of the leaders in the battle for egalitarian prayer at the Western Wall and the rights of non-Orthodox converts to Judaism — including converts from Uganda and other countries — to be recognized as legitimately Jewish in Israel.

“His persistence and Zionist commitment led him to create a lasting legacy as a leader of the Masorti [Conservative] Movement,” said Rabbi Jonathan Maltzman, who attended Jewish day school with Sacks in their hometown of Philadelphia. “He was committed to progressive causes in the area of non-Orthodox conversions and gay rights.

“Without that essential stubbornness and burning desire to help others both in Israel and in underserved Jewish communities abroad he would not have succeeded so well. It made him a thorn in the side of the Israeli rabbinate and a true hero to so many of us,” continued Maltzman, who eventually roomed with him at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. “Many of our classmates at JTS have had successful and eminent careers in the rabbinate but no one has attained the kind of international renown as Rabbi Andy Sacks.”

A certified mohel and head of the advocacy group Keren Habrit, Sacks performed circumcisions in Israel for non-Orthodox Jews, and converted countless others to Judaism. He traveled to Uganda to perform ritual circumcisions to Jews of color. He performed circumcisions and conversions in other underserved countries as well.

“Andy never lost his passion for the rabbinate, for Israel, for religious pluralism, for the disenfranchised and neglected of all stripes; in a word, for the justice that is the ultimate aim of Judaism,” wrote Rabbi Gordon Tucker, senior rabbi emeritus at Temple Israel Center in White Plains, New York and a longtime faculty member at JTS, in a statement shared to Facebook.

While he was a serious person, fighting for important causes, Sacks never took himself too seriously. He was quick with a joke or a humorous anecdote and an expert at embellishing — but mostly in fun and for fun. He was the ultimate rabble-rouser, and a party seemed to follow him wherever he went.

Though he hadn’t been a congregational rabbi for nearly 40 years, his flock of followers, believers, fans, friends and supporters are scattered all over the world, and included fellow baby boomers, Gen Xers some 20 years his junior, millennials and Gen Zers.

“He did so much tikkun in his life; he literally fixed situations that needed repair in this world,” wrote Andrea Merow, rabbi at The Jewish Center of Princeton, on Facebook, who knew Sacks since her days at what was then Akiba Hebrew Academy (now known as Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy) in suburban Philadelphia and as a camper at Camp Ramah. “It was amazing to watch him become Israeli and to make such an important mark on the Israeli community — as a teacher, advocate, mohel, Zionist, leader and friend.”

Andrew Sacks was born in Philadelphia. I first met him in 1965, when we were both in 7th grade at Akiba. Outspoken, fearless, passionate and defiant in the way many from the “question authority” generation were taught and encouraged to be, he had a sense of humor that bordered on class clown and class instigator. He was both fun-loving and inquisitive, but not someone classmates thought would end up in the rabbinate.

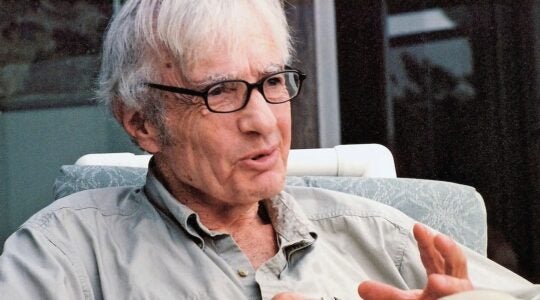

Rabbi Andrew Sacks, left, and the author in an undated photo. In the mid-1980s Sacks coached the cross country team and served as a substitute teacher at his alma mater, then known as the Akiba Hebrew Academy, in suburban Philadelphia. (Courtesy Rob Charry)

Maltzman, who attended both Solomon Schechter Day School and Akiba with Sacks, said he too was a bit surprised when he pursued ordination at JTS: “I don’t think anyone, certainly in high school and probably in college, knew of his ultimate goal.”

In the mid-1980s he had his only stint as a congregational rabbi, at Beth Am Israel in suburban Philadelphia. He would also spend some of his spare time at Akiba, mainly as the cross country coach, and as a substitute teacher.

He also showed a penchant for getting his message out through the media. He developed an unpaid side gig while in his 30s on Philadelphia music radio station WIOQ as the “radio rabbi,” calling in to discuss and explain upcoming Jewish holidays with knowledge and humor. A huge fan of David Letterman’s late night talk show then on NBC, Sacks would write irreverent letters to the show in hopes of getting them read on the popular viewer mail segment; to his friends’ astonishment, Letterman did read several of his letters on the air.

Though not particularly athletic in high school, Sacks worked his way onto Akiba’s fencing team, a sport he would also compete in at Muhlenberg College. Having struggled with his weight at times as a teenager, he would take up long distance running in his 20s as a way to shed pounds and wind down. When he began to run marathons, and registered very respectable times — under 3 and half hours — his friends dubbed him “the running rabbi” and the “fastest rabbi in the free world.”

In 1987, he immigrated to Israel, but not before his friends sent him off with a celebrity-style roast. He would dutifully return to the U.S. every fall to help lead overflow High Holiday services at Temple Beth Shalom in Manalapan, New Jersey and at Maltzman’s congregation, Kol Shalom, in Rockville, Maryland. In between the High Holidays he would visit with his young and old friends, dropping in sometimes unannounced late at night to watch Letterman, and spend time with his mother, Elaine, and four brothers.

In Israel, he devoted himself to the fight for pluralism, in a country where the Orthodox Chief Rabbinate holds a near-monopoly on Jewish religious life, including weddings, funerals and conversions.

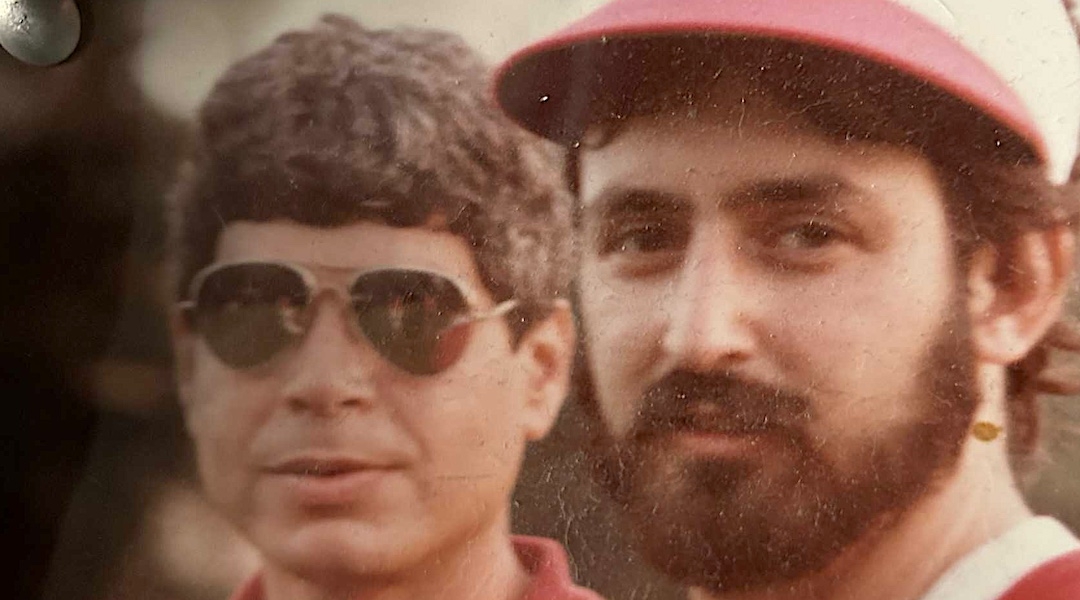

Rabbi Andrew Sacks, left, and a colleague, Rabbi Menachem Creditor, scholar in residence at UJA-Federation New York, in Jerusalem in the summer of 2023. “He was a very, very good man who fought with his entire being on behalf of others, calling for us to be our very best selves and to love with all our strength,” Creditor wrote on Facebook. (Courtesy Menachem Creditor)

“Like many of my friends, I grew up in the United States with a strong affinity for Israel. As a child we saved money to buy trees, learned Israeli songs, studied Hebrew, visited Israel and marched in Israeli Independence Day parades. I recall well that my parents encouraged me to give part of my bar mitzvah gifts to Israel. Ultimately I made Aliyah,” he wrote in 2016.

However, he wrote, “Tensions arise whenever the interests of two parties may not perfectly align. This seems to be occurring more frequently between the North American Jewish community, with its pluralistic nature, and an Israeli government that gives into haredi Orthodox demands over promises and commitments made to the Jewish communities in the Diaspora.”

On a Zoom call Sunday evening several hours after his funeral in Jerusalem, a number of his friends paid tribute, swapped stories and comforted his older brother Barry, who was in Israel for the funeral. David Binder, a close friend, fellow class of Akiba graduate and college roommate, described Sacks as “authentic.”

“Andy was an individual who was principled, compassionate and passionate about tikkun olam,” or repairing the world, said Binder. “His determination to achieve his goals was off the charts. Knowing him for close to 60 years was a blessing. I cannot imagine a world without Andy Sacks.”

Sacks kept in touch with many of the students he taught and coached in the 1980s, including Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro and his wife Lori; Rabbi Amiel Monson; Aaron Hahn Tapper, a professor in Jewish Studies at the University of San Francisco; and Ami Eden, CEO of 70 Faces Media, all graduates of the class of 1991. (70 Faces is JTA’s parent company.)

“Andy was omnipresent when you visited Israel. He was always there and you felt that he always would be,” Shapiro said on Monday. “His quips made you smile. His knowledge made you think. The night Lori and I got engaged at Yemin Moshe, we returned to Andy’s house, who let us crash there during our travels. He was the first person we saw on that special night. He was known far and wide, and left a meaningful impact on so many lives.”

Eden said during their junior year abroad, upon discovering how close Andy’s apartment was to the compound where they were staying, a number of classmates ended up taking refuge there.

“I spent a high school semester in Jerusalem and another in college, both times living just a few blocks from Rabbi Andy,” said Eden. “Each time, and for another three decades until his death a few days ago, his apartment was the place in Jerusalem that felt most like home — and the place that made the city feel like home. And I was just one of dozens, if not hundreds, who is lucky enough to be able to say that.”

Nati Katz Passow, Akiba class of 1997 and co-founder of the Jewish Farm School, wrote in a tribute on Facebook, “Since I was 17 years old, Andy has been a mentor, teacher, funcle, role model, and friend. His apartment in Jerusalem, which he so generously opened up to so many people, has been a second home for me. I found out about so much music by borrowing his cassettes, I read dozens of books that were on his shelves.”

Harold Messinger, Akiba class of 1987 and the cantor at Sacks’ old congregation, Beth Am Israel, also remembered Sacks’ apartment in a tribute he wrote on Substack: “There was always a key under the mat, and there were always people coming and going at all hours of the day and night,” he wrote. “There was an outstanding record collection of rock and pop from the 60’s and 70’s, there were reams of VHS tapes with his beloved Letterman that friends had taped and sent to Israel. There was his always well-stocked fridge. For Andy the night got started around 11 pm and you went from there.”

Always committed to peace and righteous causes in a region that was often — and still is — in turmoil, in the early 2000s, Sacks befriended and became a father figure to a teenage Palestinian boy. Anas, now 38, currently lives and works in Sweden for the government in policy implementation.

There are multitudes of us who considered Rabbi Sacks a close and dear friend, and someone we could confide in. He was loud, he was boisterous, he was persistent and he was righteous. And, his actions always spoke louder than his words.

He is survived by his four brothers, Barry, Steve, David and Eric, along with countless others who considered him our brother.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.