When Isabella Vinci stepped out of the mikvah on Nov. 11, 2021, she thought she had done everything that would be required to become Jewish. A beit din, or rabbinic court, had approved her conversion after nearly a year of study with Rabbi Andrue Kahn at Temple Emanu-El, a Reform congregation in New York, including a congregational course and one-on-one meetings.

Within a year, she visited Israel on Birthright and returned on an immersion program to teach English in an Orthodox public school in Netanya. Friends, rabbis and colleagues, she said, embraced her as Jewish.

Israel’s Population and Immigration Authority did not.

In a pair of decisions issued in January and again last month, immigration officials rejected Vinci’s application for aliyah under the Law of Return and then denied her administrative appeal.

The letters point to two main problems: She studied for conversion online during the COVID period, and she did not prove sufficient post-conversion participation in a synagogue community — particularly while living in Israel.

Vinci, 31, had to leave behind the life she had built in Tel Aviv and move back to the United States. She is now preparing a court petition with the Israel Religious Action Center, the legal‐advocacy arm of Reform Judaism in Israel.

For decades, IRAC and other non-Orthodox advocacy groups have complained about attempts by religious parties in Israel to block the recognition of conversions outside of Orthodoxy. But Vinci’s advocates say she was blocked from citizenship despite a Supreme Court ruling from 2005 allowing overseas conversions, regardless of denomination.

Her rejection also reflects a gap between the Diaspora and Israel, they say, in everything from religious practice to the adaptations made necessary by the pandemic.

“The whole world — from rabbis to strangers who hear my story — tells me I am Jewish. They see that I am putting everything on the line to be a part of our people. The only ones telling me that I’m not Jewish are within this government agency,” Vinci said in an interview, describing months of silence and what she felt was the government’s unwillingness to consider new supporting documents. “Why aren’t they putting in the work and the effort to actually understand where I’m coming from?”

Vinci grew up Catholic in a sprawling, multicultural family, spending early years in Florida and most of her childhood in Omaha, Neb. She never felt rooted in the church and developed her own spirituality as a teen. Jewish relatives and friends were part of her orbit, and she felt increasingly drawn to the religion.

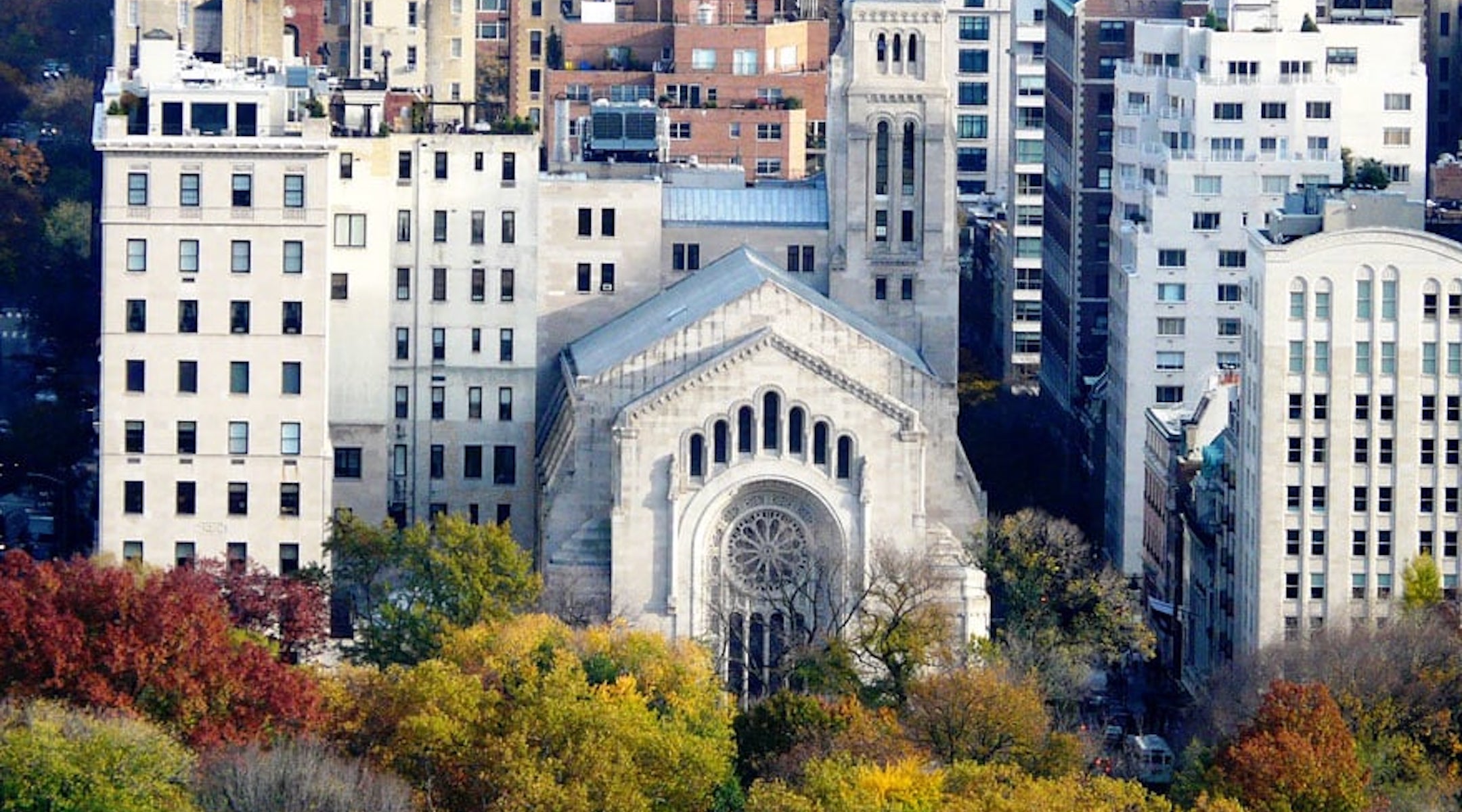

When she moved to New York as an adult, she decided to become a Jew, going through Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan, one of the most prominent congregations of Reform Judaism.

Temple Emanu-El on the Upper East Side of Manhattan is one of the largest Reform congregations in the world and the oldest in New York. (Courtesy Temple Emanu-El)

Neither the immigration authority nor the Interior Ministry, which oversees it, responded to a request for comment.

But official responses Vinci received show that decisions in her case zero in on whether her path fits internal regulations drawn up in 2014 to vet conversions performed abroad. The Israeli Supreme Court ruled in 2005 that such conversions, regardless of denomination, must be recognized, leaving it to the ministry to set criteria.

Those rules anticipate in-person study anchored in a congregation; if the course is “outside” the congregation, they require a longer, 18-month track. In Vinci’s case, officials treated her 2020-2021 Zoom coursework as external and concluded she hadn’t met the time or community-involvement thresholds.

IRAC’s legal director for new immigrants, attorney Nicole Maor, appealed the initial rejection, sending in a detailed memo. Maor wrote that congregational classes conducted on Zoom during a pandemic should be considered congregational, rather than external. She argued that the criteria’s purpose is to prevent fictitious conversions — not to penalize sincere candidates who followed their synagogue’s rules during COVID.

“The entire purpose of the criteria is to protect against the abuse of the conversion process. A person who converted in 2021, came to Israel on a Masa program to contribute to Israel in 2022-2023, and stayed in Israel to work and support the country in its most difficult hour after Oct. 7 deserves better and more sympathetic treatment,” she wrote.

She also wrote that the ministry had ignored evidence of Vinci’s Jewish communal life in Israel, from school prayer with students to weekly Orthodox Shabbat meals with a host family.

As part of Vinci’s appeal packet, Kahn submitted a letter describing the cadence of Vinci’s studies: roughly five months in Temple Emanu-El’s Intro to Judaism course alongside his own one-on-one meetings beginning Dec. 21, 2020, and continuing “1-3 times a month for 2-3 hours” until her November 2021 conversion — about 11 months in total. He listed key books and practices he assigned and attested to her active participation in synagogue young-adult programming.

A host family in Netanya provided a letter saying Vinci spent “Shabbat with our family every weekend as well as most holidays,” describing a year of Orthodox observance in their home and an ongoing relationship since she moved to Tel Aviv after Masa. The school where she taught also wrote in support.

The ministry was unmoved.

In an interview, Maor, who handles a large caseload of prospective immigrants, said Vinci’s case is emblematic of a larger phenomenon.

“It’s not just bureaucracy,” Maor said. “There’s a recurring theme — a suspicious attitude at the ministry that has become worse in recent years and makes life much more difficult for converts.”

Vinci’s case sits at the fault line between Diaspora practice after COVID and Israeli bureaucracy. Around the world, Reform and Conservative congregations shifted classes, and in some communities, services, to Zoom. Many have retained hybrid models because they work for busy or far-flung learners.

“This reality has led to a widening gap between how Diaspora congregations operate and the demands of the Interior Ministry,” Maor said.

There is also a philosophical mismatch: For the ministry, involvement in the Jewish community post-conversion appears to mean synagogue membership and attendance logs. For non-Orthodox streams, Maor said, Jewish life can be expressed in multiple ways — home ritual, learning circles, social-justice work — especially in Israel, where Jewish rhythms permeate public life.

In Vinci’s Netanya year, that life included like daily school prayer, holidays with an observant host family, and teaching in a religious environment. Maor argues that should count.

Kahn, who says two of his other converts have made aliyah without incident, said he was saddened by Vinci’s rejection given her devotion and the hoops she jumped through to satisfy paperwork and timelines.

“It wasn’t like she was mucking around in Israel, she was really doing the work and legitimately devoted to being Jewish,” he said.

After losing her legal status and appeal, Vinci returned to the United States. She took a legal-assistant job in Kansas City and is scraping together fees to file a court petition.

Maor won’t predict the outcome, but she said often cases settle before a precedent is set. The state agrees to a compromise such as additional months of study, rather than risk a ruling that forces a policy shift.

Vinci hopes the case determines not only where she celebrates the next set of holidays, but also improves how Israel treats a growing cohort of would-be immigrants whose Jewish journeys began on a laptop during a once-in-a-century shutdown and amid rising antisemitism.

“I hope my story sheds light on inter-community love and acceptance,” she said. “In our current political and social climate, the best thing we can do is be united as one.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.