Orthodox Jewish Health Care Workers Give Covid Advice that Few Want to Hear

Editor’s note: This story was produced in partnership with Slate.

In October, Blima Marcus, a nurse practitioner and ultra-Orthodox resident of Borough Park, Brooklyn, received a call from a close friend. The woman’s teenage son was showing Covid-19 symptoms — a headache, fever, and decreased appetite — after being exposed to a positive case of the virus at a local synagogue where he prayed daily.

“She wanted to know if she should get him tested,” said Marcus, 35, who works in palliative care at an oncology center but also serves in the unofficial role of medical consultant within her Orthodox Jewish community. The teenager had been continuing his regular activities, including attending synagogue. “I advised her to get her son tested immediately and instruct him to strictly quarantine until he receives the results.” Her friend replied incredulously: “ ‘You try keeping a teenage boy home all day.’ ”

“I had nothing more to say,” Marcus told me recently while driving home from work on a rainy Friday afternoon. “It was clear to me that she wasn’t prepared to quarantine.” Was she disappointed in her friend of 25 years, I asked? “No,” said Marcus. “Why should I expect more from her than from the rest of the community?”

The past few months have been tumultuous for the charedi, or ultra-Orthodox, enclaves of New York City, where an uptick in Covid-19 cases led to unwelcome attention from the media, secular New Yorkers and local officials. Last month, reports of a Nov. 8 wedding in Williamsburg attended by thousands threw the ongoing tensions between insular religious communities and government officials into stark relief. Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the city would slap the Brooklyn synagogue that hosted the event with a $15,000 fine. Nonetheless, authorities failed to stop another similar wedding in the upstate New York chasidic enclave of Kiryas Joel shortly thereafter; the nuptials proceeded despite a cease-and-desist order.

The past few months have also been a trying time for Marcus, who is now in the unfortunate position of giving advice that no one wants to hear. She has watched as her neighbors dismiss the virus and publicly defy safety measures intended to contain it. She has fought against the idea that her community has reached “herd immunity,” only to see it gain traction.

She lives just blocks away from where Heshy Tischler, a Borough Park resident, charedi radio show host and Covid-19 denialist made national headlines in October for rallying his mostly young male followers to burn their masks and rage against de Blasio. Marcus says she felt horror when Tischler targeted chasidic journalist Jacob Kornbluh for publicly criticizing his community’s unwillingness to follow the same safety precautions she’d been advocating for. She felt even more horror when Tischler’s acolytes physically attacked Kornbluth, pinning him to the ground while chanting “moser” — a derogatory Hebrew term for an informant who betrays his own community.

At the same time, Marcus, who covers her hair with an understated brown wig and, when not in scrubs, covers her elbows, knees, and collarbone, too, understands why New York City’s charedi Orthodox Jews have felt unjustly singled out for rebuke and have therefore chafed at government regulation. Back in April, after a large funeral for a local rabbi in Brooklyn drew thousands into the streets of Williamsburg, de Blasio visited the scene and called out “the Jewish community.” Months later, the mayor apologized for the statement, but many community members — smarting from a second wave of shutdowns announced in early October that disproportionately affected Orthodox-dense ZIP codes — felt the harm had already been done. Gov. Andrew Cuomo insisted that the shutdown measures were not personal, stressing in a press conference that, though the Covid-19 hot spots “overlap with large Orthodox Jewish communities,” shutdown measures apply equally to “every citizen of the state of New York.”

But members of the Orthodox community, who were already on edge after a series of violent anti-Semitic incidents in late 2019 (an assault on children in a Williamsburg housing project, a shooter threat at the Chabad Lubavitch World Headquarters in Crown Heights, a fatal attack at a kosher grocery store in Jersey City, and the Dec. 29 stabbings at a Chanukah celebration in suburban Monsey) left them feeling vulnerable and targeted, thought otherwise. From a certain vantage point, you can see why a community on edge would be wary of outsiders, who hadn’t been able or willing to protect them in the past, now swooping in to tell them how to behave in the face of a different threat.

“I Have Nothing Left”

This is not the first time Marcus has found herself caught in the middle of a tense, complicated cultural battle involving medical misinformation and an us-against-them vibe taking hold in her community. I first met Marcus in April 2019, as a measles outbreak raged in Orthodox Brooklyn, culminating in the official declaration of a public health emergency in select Brooklyn ZIP codes and the shuttering of local yeshivas. Marcus had just launched the EMES Initiative — EMES, which stands for “engaging in medical education with sensitivity,” means truth in Hebrew. When we spoke last year, she was in the midst of editing, printing, and delivering 10,000 copies of a 40-page informational booklet about vaccines to the doorsteps of charedi homes across the five boroughs to combat a similar booklet disseminated by anti-vaxxer groups. She was organizing small informational sessions for Orthodox women afraid to vaccinate their children, trying to stop a neighborhood “measles party,” and meeting with New York City public health officials and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention members around her dining room table to talk about culturally sensitive ways to reach charedi people.

Back then, Marcus was energized. Today, she seems beat. As the coronavirus ravaged her community, the EMES Initiative escalated its efforts. It’s now grown to include 30 or so Orthodox health care workers. But the challenge they are trying to meet feels nearly insurmountable. “I have nothing left,” Marcus told me on the phone a few weeks ago, as health officials tracked a “slow but steady” rise in positive coronavirus cases across New York City. “I used to be so passionate about helping the community. I used to have the patience to answer the same question for the 80th time, I used to care about helping people make healthy choices. But the work is thankless.”

I used to be so passionate about helping the community. I used to have the patience to answer the same question for the 80th time, I used to care about helping people make healthy choices. But the work is thankless.

Ephraim Sherman, a nurse practitioner at New York University hospital and another member of EMES, remembers sitting on the porch of his Crown Heights apartment on March 10, watching his fellow chasidim dance through the streets in costume. It was the Jewish holiday of Purim, a day of partying and festive communal meals. At that point, New York City had not yet issued lockdown orders. Sherman stayed home from festivities that day because he had come down with a virus, which he now assumes was Covid-19. “In retrospect,” he said, “I was watching a slow-moving bomb explode in front of my eyes.”

In March and April, the coronavirus hit the chasidic Jewish community in New York with devastating force. On March 17, the White House organized a call with 15 leading Orthodox rabbis in New York City, including prominent chasidic leaders, to urge the community to shutter key institutions and adhere to social-distancing protocols. By March 19, even before New York’s major hospitals were overwhelmed with critically ill Covid-19 patients, more than 500 cases of the coronavirus had been identified by one urgent care center serving ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Chasidic media outlets were reporting on the deaths of prominent rabbis and community leaders daily. “We were waking up each day to find out who died overnight,” said Marcus.

Sherman, a 34-year-old father of two, is Chabad-Lubavitch, a chasidic movement headquartered in Crown Heights. He soon left his regular ambulatory clinic to work around the clock in makeshift CovidD-19 crash units at NYU hospital. There, he witnessed death on a scale he had never seen before. His first day on the job, he recalled noticing a body that had been left unattended for hours. “The person had died and no one had a moment to move the body down to the morgue,” he said. “That’s when I understood the gravity of what we were facing.”

Sherman said that nearly everyone in his community knows someone who died from Covid-19 in the spring. “Many believe that their family members died in the hospital because of neglect,” he told me. “It’s easier to accept that your mother was sick and the hospital neglected her, rather than believe that the grandkids came over, gave Bubbe Covid, and then Bubbe died.”

The conditions under which the chasidic community experienced the first Covid-19 wave created a “perfect storm,” said Nesha Abramson, the director of community health outreach at Vaad Refuah, a Brooklyn-based patient advocacy center that primarily serves the local charedi population. Many chasidic people died alone. Overwhelmed hospitals failed to communicate well with family members. “For a community with real historical and epigenetic trauma, mistrust of systems external to the community are latent,” Abramson said, referring to the Holocaust.

In Abramson’s eyes, the suffering of the community in March and April contributes to “a current communal dissociation from the possibility that something like this could happen again.” “Folks are shutting themselves off,” said Abramson, who works alongside rabbis to gain community trust and compliance and has volunteered with the EMES Initiative. “For many, the trauma is so intense that there is literally nothing I can say to make them hear me.”

“Fear and Misinformation”

For EMES, spring 2019’s measles outbreak was a kind of harbinger of things to come. Back then, Abramson worked closely with Marcus to battle “overwhelming fear and misinformation” about the MMR vaccine. “As someone who was constantly preaching about the danger of the measles virus, I became a target for misdirected anger,” said Abramson. A fellow parent at her young son’s local yeshiva threatened to sue her for insisting vaccinations be mandatory for all students, she recalled. (Slate reached out to the parent, who did not respond to a request for comment.)

Now, Abramson says, the community’s reaction is far more intense and antagonistic than it was during the measles outbreak.

“People say wild things to me, on the phone, in the grocery store. People accuse me of using Nazi tactics to make people stay isolated in their home,” she said.

A prominent community doctor whom I initially planned to interview for this article eventually declined to talk to me; after publicly decrying his community’s lax response to Covid-19 safety measures for months, he is no longer speaking to the media, a source close to him told me, because the “personal fallout” this doctor has experienced for chastising his fellow community members has been “severe.”

(Within the Orthodox community, there are several ways community leaders can quash dissent. One particularly effective method is to threaten a person’s marriage prospects — or the marriage prospects of that person’s children or grandchildren. The threat of poisoned matchmaking prospects, or “shidduchim,” as it is colloquially called, can quickly muzzle those who might otherwise be compelled to speak out on issues from child sexual abuse to Covid-19 safety protocols.)

Sherman, the Chabad-Lubavitch father who has since returned to his local ambulatory practice in Crown Heights, has not faced anything quite as scary. But he says that his efforts to pressure his fellow community members to comply with Covid-19 safety measures are often met with “anger, frustration, and contempt.” “Somehow,” he told me, “I’ve become the threat.”

One catalyst for this anger was the local government’s handling of Covid-related school closures. Dr. Moshe Lazar, a pediatrician with clinics in Borough Park and Midwood, is still deeply frustrated about this. He knows charedi Orthodox Brooklynites are not blameless; he acknowledges that certain superspreader events at the end of summer and early fall — including a handful of large weddings where many partygoers were unmasked and did not observe social-distancing rules — contributed to the uptick of positive Covid-19. “I can’t argue on the wedding situation,” he told me. “Our community was not ready for it, and we paid dearly.” But he thinks the community’s anger is partly justified because of what happened with the schools.

Lazar worked closely with local yeshiva schools in Brooklyn and Queens to open safely in time for the new school year. But many of the institutions he helped reopen in September were then forced to close by city officials, citing a rise in positive Covid-19 tests in nine New York City ZIP codes, nearly all of which have significant Orthodox Jewish populations.

“The day the city closed down Darchei Torah, they lost,” said Lazar, referring to a prominent boys yeshiva in Queens that the Department of Health shuttered in mid-September after an uptick of positive Covid-19 cases. He said the “mainstream Orthodox yeshivas,” like Darchei Torah and its sister school, Torah Academy for Girls, worked closely over the summer with the Department of Health to safely open schools in the fall. “Social distancing, masks, no lunch in the lunchroom — they complied with all of it,” said Lazar.

He believes that the way de Blasio and Cuomo announced new lockdown measures in October — with last-minute emails to school principals and inconsistent messaging about why the schools had to shutter when others in the city did not — cost city and state officials the trust and goodwill of the Orthodox mainstream. “They steamrolled Jewish schools and made everyone feel like garbage, when we had worked for months to cooperate closely with the DOH,” Lazar said. “To contain a pandemic, the government officials need to test, trace, and contain,” he said. “Not test and then immediately punish the community by shutting down schools.”

(In an Oct. 5 press briefing, de Blasio shared that between Sept. 25 and Oct. 5, 1,351 Covid-19 tests conducted in more than 35 schools in the “nine ZIP codes of highest concern” had produced only two positive tests. In an interview with The New York Times, the mayor conceded, “We have seen very little coronavirus activity in our schools.” Despite that acknowledgment, schools in the nine “red zone” ZIP codes were forced to shutter long before the citywide shutdown of public schools in late November.)

Since those lockdowns, several reports in Jewish news outlets have indicated that Orthodox community officials are actively discouraging members from testing their children for Covid-19 in order to avoid further school shutdowns. “Once you punish, it diminishes any incentive to test, which makes tracing and containing the virus that much harder,” said Lazar. The governor and mayor “effectively put a target on the Orthodox communities’ back,” he said. “The narrative no longer [felt] like all New Yorkers versus the pandemic — to many Orthodox Jews, it feels like us versus them.”

The narrative no longer [felt] like all New Yorkers versus the pandemic—to many Orthodox Jews, it feels like us versus them.

That feeling of being targeted plays out in other ways as well. “I’ve been screamed at — ‘You people, you Jews,’ ” Dalia Shusterman, a chasidic mother of four from Crown Heights told me of going out without a mask. “Even when I’m outside and not near anyone, people jump back from me with their hands in the air like they’d seen the plague.” And so, she remains resolute: She will not buy or wear a mask. “If you’re ever the slave to public opinion, you’ll never be happy.”

“It’s a control issue,” another young chasidic mother who lives in Crown Heights told me.

Nearly one year after Marcus and EMES pivoted from focusing on measles to this deadly new virus, new positive cases of Covid-19 continue to rise across New York City, with a seven-month statewide high of 5,972 recorded last week.

Within the five boroughs, Orthodox-dense “clusters” now account for less of the increase, and the yeshivas are open again, at least for the moment, even as many New York City public schools are not. In Williamsburg, a handful of local Jewish agencies are paying community members to distribute masks several hours per week and hang up posters, some in Yiddish, publicizing safety and social-distancing protocols. But according to Marcus, compliance among her fellow community members is poor, even as positive cases creep back up.

“I love my landsmen, but I will never ever understand them,” she posted on Facebook two weeks ago, after a young mother in her community died from Covid-19 in late November. Even as the community reeled from the enormity of the loss, Marcus says she continues to face ridicule for wearing a mask.

I love my landsmen, but I will never ever understand them.

The last time we talked, Marcus was weary but still at it. She is in touch with other members of the EMES task force every day, exchanging WhatsApp messages about lockdown updates and orchestrating Yiddish robocalls to encourage masks. She has reached out to city health officials who were particularly helpful during the measles crisis, people who had been proactive in asking for her thoughts on culturally sensitive ways to approach the charedi Orthodox community. This time around, though, she says those same officials have been largely unresponsive to her messages. (In a September Covid-19 briefing, de Blasio claimed outreach to the Orthodox community has been “nonstop.” “I would be curious to know who exactly they are in touch with,” said Marcus, an edge to her voice.)

On the horizon is what Marcus and her EMES colleagues know will be the formidable challenge of introducing a vaccine to a wary community. Early in the coronavirus crisis, Marcus remembers thinking that the virus might “actually be the reality that anti-vaxxers need.” Maybe, just maybe, she thought, the pandemic might finally “drive home the risks of what happens when we don’t vaccinate.” But she never anticipated the way mistrust and misinformation would overtake her neighbors. “I should have seen it coming,” she said.

“During the measles crisis, we fought to get people to take a well-researched vaccine that has been around for decades,” said Abramson. “Now we’re going to expect folks to accept a new vaccine on the back of this sort of community trauma?” While news of a potential Covid-19 vaccine has been a ray of hope in an otherwise bleak landscape for many of us, Abramson said the headlines made her feel “more sad and scared than I’ve ever been throughout corona.”

As winter encroaches, Marcus and EMES are fighting several battles at once. They want more financial support from the city and state to fight misinformation. They want more support from leaders within their own community. They desperately want to find a way to convince the men and women they pray with, whose children they send their own children to school with, to take Covid seriously, and not take a guy like Heshy Tischler seriously at all. But with the trauma of the first surge, the city’s bungled response, the political climate, and an entrenched distrust of secular restrictions, many of the people they are trying to influence now feel beyond their reach.

“I can’t go on living in fear,” a young Orthodox woman who lost her father-in-law to the coronavirus in March recently told me, explaining that she tested positive for Covid-19 antibodies and therefore thinks she is inoculated against reinfection. She is not interested in wearing a mask or taking other precautions, and she believes that God, whom Jews refer to as “Hashem,” has a plan. “Not everything is in our control,” she said. “Hashem has something to do with it.”

Does The New York Times Have a Chanukah Problem?

Jewish Twitter was not amused by a New York Times op-ed by an author saying why she no longer celebrates Chanukah.

Sarah Prager, an historian of LGBTQ history, explains that her father is Jewish and that growing up her family attended a Unitarian Universalist meeting house. She writes that Christmas was the most important holiday in her home. As a parent herself, she no longer lights the Chanukah candles. “I am not Jewish and it doesn’t feel authentic to celebrate a Jewish holiday religiously,” she writes.

Well, okay then.

The angry comments focused on why The Times would devote space to what is essentially a rejection of a Jewish holiday by someone who doesn’t regard herself as Jewish. “Truly impossible to imagine @nytopinion allowing a random white person to appropriate the religion of any other minority — and purely for the purpose of discarding it. Gross — and revealing — on so many levels,” tweets Batya Ungar-Sargon, opinion editor of the Forward.

“To check my memory, I searched @nytimes for last decade’s #Hanukkah op-eds,” tweeted Rabbi Jill Jacobs of T’ruah. “Almost all made fun of holiday, declared [it] ‘hypocrisy,’ or ‘discovered’ that the childhood story wasn’t ‘true.’ Can NYT not find anyone with actual Jewish knowledge to write a thoughtful piece?”

My beef with the article was its lack of significance. “I no longer follow a tradition that never meant much to me in the first place” (I’m paraphrasing) is a very thin reed upon which to hang an essay.

I often tell op-ed writers to put their drafts to the “this as opposed to what?” test. A strong essay arguing for something is usually arguing against something else. I’m not sure what that “something” is in Prager’s case. Are outsiders or family members demanding that she celebrate Chanukah and asking that she explain herself? That’s not clear from the essay, and unlikely given that she and her wife have “no religion at all.”

Is she arguing against religious coercion, because “the old way hurt or didn’t fit”? Perhaps – but is Chanukah the field on which to fight that particular battle? With a powerful Christian Right in this country carving out exemptions from anti-discrimination laws based on their religious beliefs, and with a conservative propaganda machine devoted to a mythical “war on Christmas,” why pick on a minor holiday celebrated by less than 2% of the population?

And it’s not like it is news or surprising that people with Jewish heritage are letting go of Jewish traditions. Prager seems to be creating a permission structure for people to do something that they have been doing in droves for decades. Ironically, Chanukah is often the last Jewish custom that secular Jews relinquish.

Defenders of the article said she is merely describing an experience common to many families with attenuated Jewish roots, who part with vestigial customs with a combination of wistfulness and defiance. If so, Prager doesn’t make it a very interesting experience – she leaves Chanukah behind with a nostalgic shrug, with little discussion of what would be worth preserving in the first place. “Just like I did, my kids will celebrate Santa and the Easter Bunny, not a religion,” she writes.

(Compare her longing to “dust off the menorah” with the difficult and consequential struggles of the formerly charedi Orthodox men and women, profiled in a recent New Yorker article, who are torn between the all-enveloping belief structures of their youth and the uncharted territory of secular life.)

Both Ungar-Sargon and Rabbi Jacobs suggest there is something systemic about The Times’ choice to run the article ahead of Chanukah. I’ve often argued that The Times is not anti-Semitic, but rather tends to reflect the predilections of secular Jewish intellectuals — on its staff and over-represented among its readers — who take a bemused approach to Judaism and a conflicted approach to Israel. It’s a point of view that treats Jewish traditions less charitably than other religious traditions, in part because family members often treat each other worse than they would outsiders.

And as Jacobs notes, The Times has gone down this path before when it comes to Chanukah. I remember a snarky 2010 piece by novelist Howard Jacobson saying Chanukah didn’t feel authentically Jewish because its heroes are soldiers and religious zealots – perhaps the quintessential critique of a Jewish tradition by a secular Jewish intellectual. Another novelist, Michael David Lukas, picked up on this theme in 2018, calling Chanukah “an eight-night-long celebration of religious fundamentalism and violence.”

At least Jacobson and Lukas are arguing against something. Prager’s article reads like the confession of a life-long vegetarian who once ate meat as a child, and doesn’t really miss it.

Prager’s article reads like the confession of a life-long vegetarian who once ate meat as a child, and doesn’t really miss it.

One essay wouldn’t mean much to me, even within the pages of a newspaper as widely read and influential as The New York Times. What disappoints me is another lost opportunity to reflect on Chanukah and Jewish tradition in ways that are neither sermonic and pious, nor secular and snarky. There are plenty of Jewish voices who can frame Chanukah within the context of modernity, critiquing its uncomfortable aspects while preserving the ways it has been reimagined according to a modern, even liberal, Jewish understanding of religious freedom and the dilemmas of assimilation.

But that would demand editors and gatekeepers to take seriously the idea that religion and intellectual rigor can co-exist. It would mean engaging with the rabbis and everyday Jews who cherish Judaism not as a series of quaint but outdated gestures — no more or less significant than Santa or the Easter Bunny — but as a tradition of texts and actions that can speak deeply and seriously to the present moment.

Andrew Silow-Carroll (@SilowCarroll) is the editor in chief of The Jewish Week.

Let’s End Discrimination Against Orthodox Jewish Girls and Women in France

My name is Tali Fitoussi, and this is my journey as a French Orthodox Jewish woman trying to stay within an institutional Orthodox context.

Even before college, my religious education was already gendered: my little brother was asked every Shabbat to go to the synagogue, and girls were not encouraged to do so – which at the time seemed normal to me. With interest, I followed his progress: learning cantilations, his different aliyot to the Torah, and working on his haftarah. When I reached the age of Bat Mitzvah, nothing was planned in the synagogue to mark or celebrate this milestone in my life. There was no buffet kiddush after the service. I didn’t do any learning or preparation for the occasion. Instead, my parents offered to rent a separate space to give me the opportunity to deliver a speech in a separate room. On the other hand, a few years later, after my brother participated in a 6 month training course and read from the Torah for his Bar Mitzvah, he had a celebration in the synagogue.

As a child in a Jewish private school, I became attracted to learning Gemara, a subject which was not taught to girls. When I probed, my teachers explained that those texts weren’t a good fit for women’s skills: women were more emotional, less prone to understanding and appreciating Gemara. My desire to learn did not fade, and during my senior year, I became interested in a gap year program. My school brought in representatives from several seminaries. However, the men’s programs appeared to be serious and multidisciplinary, while the girls’ seminaries proudly offered courses geared towards becoming good Jewish wives and mothers. These seminaries were generally located in Israel. Disappointed, I convinced myself to skip a gap year and go straight to college.

When I probed, my teachers explained that those texts weren’t a good fit for women’s skills: women were more emotional, less prone to understanding and appreciating Gemara.

During my studies, I became involved in several student groups, including one that gathered young leaders every week to prepare and deliver a dvar Torah. I loved the idea of empowering ourselves as a young generation, over our centuries-old texts and making them ours again. I immediately offered to prepare a drasha (class). I was told no: the laws of tsniut – modesty, propriety, decency – would prohibit women from giving classes in front of a mixed audience. Instead, I was offered the opportunity to organize classes for young women only.

A few months went by, and Simchat Torah festivities were held in the synagogue. Like every year, the women watched the men dance, throwing sweets and clapping their hands. That year, I requested a sefer Torah for the women’s section, so that we could hold it as we danced among ourselves. The answer was quick to come: “it’s too heavy for a woman, and besides, you might be nida – in a state of impurity related to the menstrual cycle – and therefore forbidden to touch a Sefer Torah. Therefore, as a precaution, we can’t give you any. Sorry.” I learned later that Rambam, for instance (Laws on Sefer Torah 10:8, based on Berakhot 22a), explicitly allows a woman to hold the Sefer Torah while menstruating.

A few years later, I was no longer tied to any particular community or synagogue. I did everything I could to understand these differences, why I accepted them in a Jewish context when they would have revolted me in a non-community context.

A few years later, I was no longer tied to any particular community or synagogue. I did everything I could to understand these differences, why I accepted them in a Jewish context when they would have revolted me in a non-community context. I enrolled in the SNEJ, Jewish studies program for young adults organized in Paris by the IAU, and then in a mixed course of Gemara study. I also organized with my association parallel Carlebach services, in which women could dance and sing on their side of the mechitza. To celebrate our first Shabbat, I gave the honor of leading kiddush to a woman. It was not meant to be a provocative act, simply a way of honoring a friend with an action that, as I had recently learned, did not seem to pose any halakhic problem. Even in this progressive context there was a general outcry. I was asked not to repeat it, or else most of the members would leave the association – and since then I have felt too uncomfortable to do so again.

Not long ago, I got engaged. I learned that I was required to follow courses on nida in order to validate my wedding at the French Consistory (the French Orthodox institution in charge of administering Jewish Orthodox congregations). I learned that these classes might solely cover the practical exposition of the rules of nida. I was horrified to see that the meaning behind these rules didn’t matter, that the women I would meet in those classes would not prepare me psychologically for or explain the details of the wedding ceremony, and that they would not help me understand the difficulties of a get. Nor would they talk about the couple, about love and spirituality – just nida as a mandated precept. Thankfully, and with the help of the Facebook group “Judaism and Feminism,” I found an exceptional teacher who followed me and brought me all the knowledge I needed, but I know that my case is the exception to the rule.

For our wedding ceremony, I suggested we have some women come up under the Chuppah to read some verses alongside the seven men who would be reciting the seven blessings of the bride and groom, and to stand next to the male eidim (legal witnesses). Members of my family threatened not to come to my wedding out of shame. We wanted to sign Tnayim – an agreement in a different document adding terms to the Ketouba in order to avoid potential problems about receiving a get – and the two witnesses we had chosen in the first place declined the invitation either out of fear or ideological disagreement. We did not give up, and organised what I would call the first Modern Orthodox wedding in a Jewish consistorial synagogue, thanks to our rabbi who helped us find halakhic possibilities in our propositions.

I want to study freely, and I want a say in the choices made in the synagogue. I want to be free to challenge the superstitions that bind halakha in a straightjacket of bigotry.

Today, I want to build a welcoming Orthodox Judaism, which does not bring me back to a status that civil society has long taken for granted. I want to study freely, and I want a say in the choices made in the synagogue. I want to be free to challenge the superstitions that bind halakha in a straightjacket of bigotry. A Halakha that, when studied, seems much more progressive than the current French Orthodox Jewish society. I want our institutions to condemn these sexist practices based on obsolete traditions, not on laws.

Multiple initiatives stemmed from the first time I shouted my disappointment in a video on Facebook that has since been viewed 5,000 times. The United States’ community is ten years ahead of the French one in terms of gender studies and feminism. We will catch up because we owe it to Jewish women to facilitate their ways and to give strength to their voices. We will not be silenced just because silence is what has maintained the status quo for years.

Instead, we will build websites to gather information, and schools and courses for people to learn how to fight back against mediocrity. We will build a community that is a safe space for women and men to ask questions and get real answers, for them to speak up and own their own Jewishness. And all this, we will build inside the Orthodox community.

Tali Fitoussi is a French Jewish Orthodox woman. She advocates a wider access to the study of Judaism for women, and a more equal treatment of women and men in her community. She attended a year long educational program on Jewish studies, and keeps attending seminars of Tashma, a French branch of Pardes institute. She has co-created Pilpoul, an association that offers a co-educational study of Talmud and organizes monthly shabbat services aiming at improving gender equality. She is involved in the only Orthodox women’s Megillah and Torah readings in France. She also speaks up about these issues through different networks such as Dieu.e, an interfaith podcast on Orthodoxy and feminism, or on blogs such as Ayeka or jeducationworld.com , and social networks. Tali Fitoussi was interviewed in the “feminist and believer” podcast Dieu.e, in French, which can be listened to by clicking here.

Tali Fitoussi is a fashion graduate and is therefore passionate about Jewish Costumes. She also gave and attended various conferences and lectures notably at Limmud Paris on the issue, researching these topics extensively in the process. Her next projects for a more equal Jewish community include building a Kollel with Myriam Ackerman Sommer (Maharat French student) and a website gathering textual resources for French Orthodox women on numerous relevant topics.

Posts are contributed by third parties. The opinions and facts in them are presented solely by the authors and JOFA assumes no responsibility for them.

Prince Charles calls Rabbi Jonathan Sacks ‘a light unto this nation’ at ceremony marking 30 days since chief rabbi’s death

(JTA) — Prince Charles of the United Kingdom called former British Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks a “light unto this nation” at a tribute marking the end of Judaism’s 30 days of mourning since Sacks’ death.

Charles, whose title is the Prince of Wales, eulogized Sacks, who died at 72 on Nov. 7, on a prerecorded video broadcast Sunday that was viewed by thousands of spectators from around the world. The ceremony also featured speeches also by Israeli President Reuven Rivlin, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Lord Jacob Rothschild.

“Through his writings, sermons and broadcasts, Rabbi Sacks touched the lives of countless people with his unfailing wisdom, with his profound sanity and with a moral conviction which, in a confused and confusing world, was all too rare,” Charles said.

Rivlin noted Sacks’ advocacy for liberal democracy as the “best way of keeping the values of monotheism” because “liberal democracy makes space for differences.”

Sacks was a frequent contributor to British media and highly regarded across the English-speaking world and beyond. In the Jewish world, he was celebrated both for his rabbinical writings and interpretations and for his ability to teach non-Jewish audiences both the past and present of Judaism and Israel in relatable terms.

“Rightfully, so much Kavod came to him and through him to all of us,” said British Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, who succeeded Sacks in 2013. “Thanks to him, we’re all able now to stand tall.”

Rabbi Ari Berman, the president of Yeshiva University, said that Sacks impressed upon him “that today there’s a dual mission for our people: to protect and to project.”

Berman added, “Lord Sacks showed us what we may become. And for that, we remain forever inspired and forever grateful.”

Sacks’ widow, Elaine, said that over the past 30 days — a mourning period known as sheloshim — she had found herself wanting to share the outpouring of love and sorrow that she has received with her husband.

“I want to walk up the stairs to his study and see him sitting there writing away,” she said. “‘Listen,’ I will say. ‘Look what is happening. Look how many people have learned from you, revere you, love you. They are writing such moving things about you. Look what you have achieved.’ He will look up at me deeply and nod and say, ‘There is still so much to do, and he will get straight back to work.'”

Joe Biden poured him a drink and he gave Jared Kushner an aliyah. Rabbi Levi Shemtov is optimistic about DC’s transition.

WASHINGTON (JTA) — Some of Rabbi Levi Shemtov’s most prominent congregants are likely to leave his synagogue soon, but the Washington, D.C., rabbi isn’t sweating it.

After all, Shemtov has been through decades of presidential transitions as Chabad’s main man here, and even though this one is unfolding unusually, he’s confident he can continue to offer a spiritual home for people on both sides of the political aisle.

“I am a rabbi in the political arena,” Shemtov told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “I’m not a politician in the rabbinical arena. There’s a difference.”

Shemtov directs American Friends of Lubavitch (Chabad), an outreach and fundraising body and synagogue for the global Hasidic outreach movement. Growing up, he watched Chabad negotiate Washington under the guidance of his father, Rabbi Abraham Shemtov, who launched the tradition of lighting a menorah in front of the White House. That was during the Carter administration, in 1979.

Levi Shemtov began running Chabad’s D.C. operations in 1992, the year that one one-term Republican president (George H.W. Bush) lost to a Democratic challenger (Bill Clinton). Twenty-eight years later, another Republican president has lost to a Democrat after his first term — but this time, members of the outgoing president’s family belong to Shemtov’s congregation.

Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner live a seven-minute walk from the shul, which doubles as Shemtov’s home, and attend services there regularly. Shemtov’s intimate and substantive relationship with the outgoing first family doesn’t stop there: He also had a small role in the recent treaties between Israel and Arab states.

For years, he has played matchmaker between Jewish organizational leaders and some Arab nations, whose embassies neighbor his headquarters near Washington’s Dupont Circle. Some of the seeds of the breakthrough Abraham Accords, signed in September between Israel, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, were in his impromptu blessing of the King of Bahrain at a 2008 event, which opened the door to further Arab-Jewish cooperation.

Now, not only is Joe Biden promising a 180 on just about every policy President Donald Trump introduced in his four years in office, but Trump has also broken virtually every norm aimed at facilitating a transition. The outgoing president is also rushing through executive orders that could cripple Biden’s first months in office.

Shemtov is not fazed by the machinations of a Trump administration determined to sabotage liberal agendas on its way out the door, or by the calls from liberals for retribution on Trump and those adjacent to him.

He stresses that he’s no politico. He has lobbied for specific Chabad agenda items — such as prison reform or the Congressional Gold Medal for the late Lubavitcher rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson— but generally leaves policy matters to others. And while he is a fixture at political conventions, he says he has declined invitations to deliver opening convocations, because he would then be unable to do it at the opposing party’s event.

“When we have an event, which features a prominent official from one side, we will either have one from the other side at the same time, or oscillate at different events between the two,” Shemtov said. “Sometimes I’ll be asked to participate in something [that] can appear partisan, and I will only do so if there’s agreement that I can do the same with the other side.”

Shemtov said he anticipates a warm relationship with the incoming White House. He recalls Biden quoting Schneerson, off the cuff, and the president-elect once poured him a drink. Years ago, his father would ride the train with the then-Delaware senator, whose nickname is “Amtrak Joe.”

Shemtov is ubiquitous in town no matter which party is in power, especially (in pre-pandemic times) around Hanukkah, when he supervises the koshering of the White House parties and lights of the menorah in front of the White House. He is almost always accompanied by a top Jewish administration official and his father as the crane rises towards the massive candelabra.

Alongside those roles, he makes appearances at the other parties that proliferate around the capital. He is in his element regaling a small crowd with Jewish tales of the capital. A jovial guy in a beard doing the rounds in December would be his copyright, but, well, it’s been copyrighted.

“He glides seamlessly between Democratic and Republican Washington,” said William Daroff, the CEO of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations. “He was as much a fixture in the Obama White House as he was in the Trump White House.”

Shemtov also is, well, a Chabad rabbi and invested in Jewish outreach, a fertile field in a city that is a magnet for young, single ambitious Jews seeking careers in politics and policy. And like other Chabad rabbis, he wants his friends to learn more Torah. Except in his case, his friends are the kind of political lifers who are well known among the well-known — the names that excite attention among Washington insiders for their formidable backroom politicking, but who barely resonate among the general public.

Shemtov says he gives a select few shiurim, one-on-one lessons in Jewish readings. Among his current students he names Mark Penn, the Clinton-era pollster who has in recent years raised eyebrows by becoming an outspoken Trump supporter, and Bill Knapp, one of the Ks in SKDK, the powerhouse consultancy that is helping to put together the incoming Biden administration.

What do these folks want to know? Shemtov did not get into the particulars of what each student is learning, but described generally what he tells his study partners.

“When we study Pirkei Avot,” the Ethics of the Fathers, a rabbinic text of moral adages, “we get to touch on subjects like political power, and how fleeting it can sometimes be and how one must be wary in the political world of the true nature of allies. And we have seen over time, bitter enemies become friends and vice versa. And, you know, to me every time I can watch people from different persuasions appreciate the perspective of the other I see a sanctified moment in the political arena.”

Knapp said in an interview that he has been taking lessons with Shemtov for several years intensively although the families have known one another for decades. “There’s a certain complexity to his shiurs which I enjoy,” he said.

“The lessons you learn about humility, the lessons you learn about right and wrong and the lessons you learn about listening to others, about respecting others, the Torah is a guide to living,” Knapp said. “The lessons are meaningful without being trite.”

The Trump-Kushners have remained steady congregants of his, notable considering the news recently that parents furious in part at their pandemic behaviors drove them out of a local Jewish school. Shemtov put an early stop to such concerns at his synagogue.

“Some people had concerns,” he said. “I told the shul one thing. Two lines. I said, number one, everyone is welcome to come to this shul, except people who say other people are not welcome. Second thing is it’s not my synagogue or anyone else’s. It’s God’s synagogue, I’m privileged enough to run it. And anyone who wants to come here and pray is welcome.”

He credits the couple for keeping it real, at least at his shul.

“There’s a famous story where an elderly woman walked into shul and nobody stood up. Every seat was taken, people were standing-room-only. And as soon as Ivanka saw her she stood up and gave the woman her seat and wouldn’t take anyone else’s seat that was offered to her. She stood at the side until the service was over. There were no cameras. No media reports. Just like 150 Jewish women looking on and saying that’s a real mensch.”

He said Kushner, a Levite, would defer to other Levites if they were present for the second Torah reading in a service, which traditionally goes to Levites. Once, when Kushner was called up to the Torah, Shemtov witnessed a rare instance of bipartisan comity.

“I even had this moment where Jared had a special Aliyah of Levi,” he said. “Standing next to him was someone who actually wrote a scathing article against him. And the whole idea of the shul was, Baruch haShem, that at least for one moment any differences have been transcended by the sanctity of the synagogue.”

He sees Biden as someone who has affection for the Jews, as well. The incoming president, he said, surprised him once by recalling a saying of the Lubavitcher Rebbe extemporaneously while speaking at a Chabad conference. Shemtov realized how steeped Biden was likely to have been in Lubavitcher lore as a result of those Amtrak journeys with his father.

“He was giving his prepared remarks, but then went off on his own for a good half hour,” Shemtov said. “And in the middle of it he turns to my father. ‘Rabbi Shemtov, did you not teach me that the Rebbe said that what you do one day is not enough for the next day and every living thing must grow?’ This was not in his prepared remarks. This must have been taught to him over many, many years.”

Then there was the time in 2011, after Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addressed Congress, that Biden poured Shemtov drinks. It was a significant moment for Shemtov, whose grandfathers were once imprisoned by the leaders of another country, the Soviet Union.

“I see Joe Biden walking up the bar,” he said. “So I got out of the way and said, ‘Please, Mr. Vice President.’ He says, ‘No, rabbi, what are you having?’ I said, ‘After you.’ He said, ‘No no no no no, I’m Irish, and you’re now in my house, so I’ll pour you a drink. Tell me what you want.’ So a vice president pouring you a drink at the bar is a pretty interesting experience for this young American Jew.”

He has no less trouble getting along with the Arab ambassadors who work near him. He says he finds commonality in the two ancient faiths of Judaism and Islam, saying his interlocutors are often “fascinated” by his practice.

Shemtov’s ability to get along with others hasn’t always extended to his own colleagues. A turf war between him and a rabbi at George Washington University ended up in court. It was settled. And a different dispute between him and a Chabad rabbi in Maryland resulted in a rabbinical court concluding that Shemtov is the official leader of all Chabad activities in D.C.

But the only thing giving Shemtov any anxiety right now — and the only time he skated close to political commentary while speaking with JTA — is the fate of the Abraham Accords, which Kushner brokered.

The accords advanced the idea that the U.S. does not need to first achieve Israeli-Palestinian peace to normalize relations with other Arab countries. Biden is seen as likely to make Israeli-Palestinian talks more of a priority. Shemtov sees the recent treaties as more evidence for his philosophy — that people of different backgrounds and ideologies can still get along.

“You know, peace and process don’t always get along with each other. And what we have right now is a significant chunk of the Arab and Muslim population, recognizing more and more how the Jewish people at our core mean no ill toward anyone. And we can live in peace rather easily. I’ve watched with pain as Israel was pinched for continued concessions which didn’t quite bring the promised results. I think the best result we can have is when people work together.”

The real story behind ‘Mank,’ the new movie about the Jewish screenwriter who brought us ‘Citizen Kane’

(JTA) — Acclaimed director David Fincher’s highly anticipated film “Mank,” on the Jewish screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz and the story behind his writing of the classic film “Citizen Kane,” hits Netflix on Friday following a short theater-only run. It’s already being considered a front-runner for several Oscar nominations.

Beyond “Citizen Kane,” Mankiewicz worked behind the scenes on dozens of famous films from the silent era into the 1950s — among them “The Wizard of Oz” and the comedy “Dinner at Eight” — without often receiving credits. He was known in Hollywood’s inner circles for his sharp wit, as well as his alcoholism, and numerous critics have described Mankiewicz as one of the most influential screenwriters of all time.

But Mankiewicz has never gained the fame of “Citizen Kane,” nor its director and star, Orson Welles. And it’s likely that only the most zealous of film buffs are aware of the Jewish sides to Mankiewicz’s story. Here’s some of that history.

Meet the Mankiewiczes

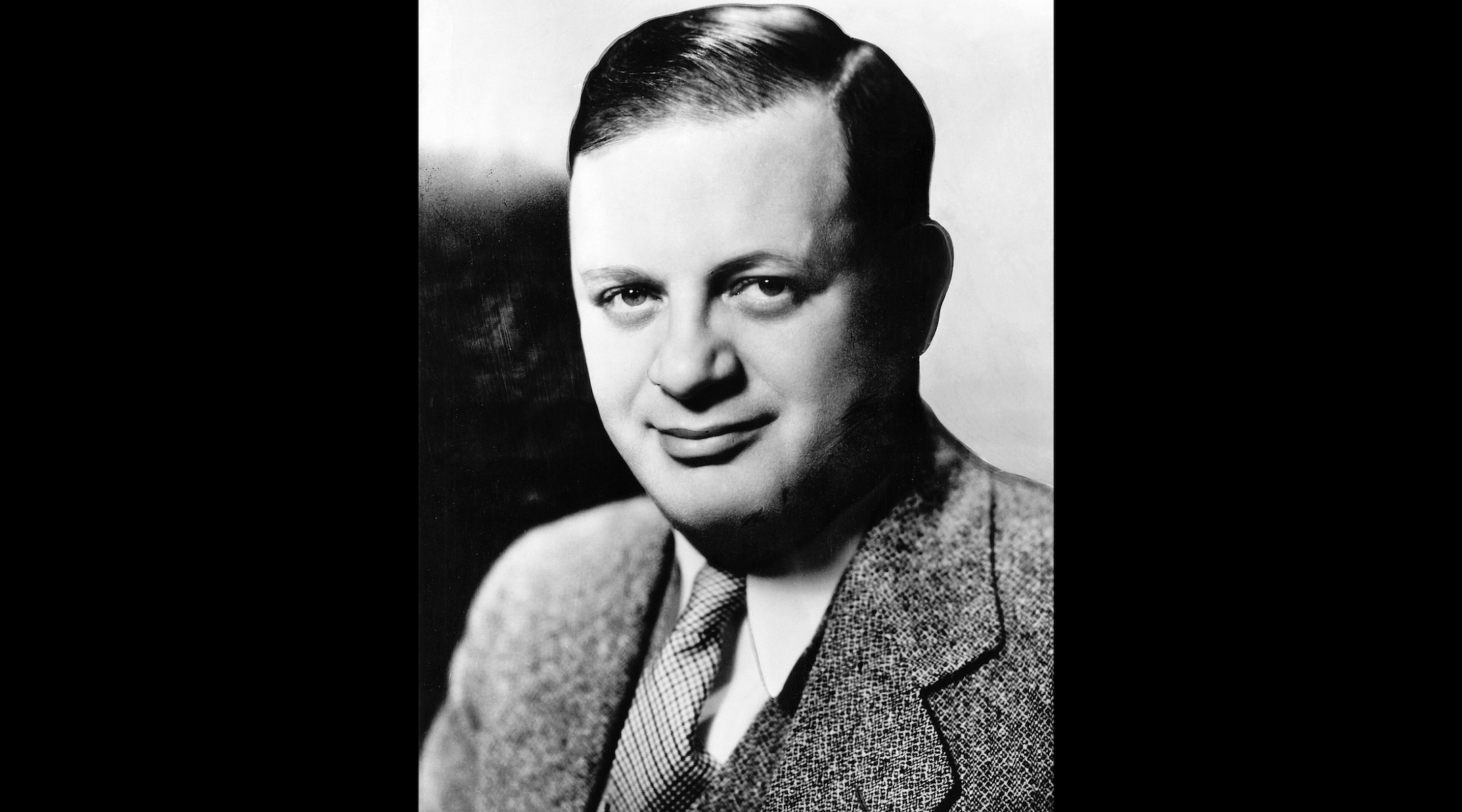

The real Mankiewicz in 1943. (Wikimedia Commons)

Mankiewicz was the son of German-Jewish parents who immigrated to the United States in the late 19th century and spent most of his early years in New York City. He has been far from the only noted member of his Jewish family. His prominent relatives include:

- His late brother, Joseph, won multiple Oscars as a director, screenwriter and producer.

- His son Frank was a political aide to Sen. Robert Kennedy and eventually a president of NPR.

- His late son Don was an Academy Award-nominated screenwriter and author.

- His late nephew Tom was a screenwriter and director who worked on multiple James Bond films and other blockbusters.

- His grandson Ben is a host on the Turner Classic Movies channel and a co-founder of The Young Turks, a popular progressive online politics show.

A fledgling Jewish journalist

Before becoming a screenwriter, Mankiewicz served in the Army and Marines, then worked as a journalist, first as a reporter in Berlin for American newspapers such as the Chicago Tribune, and then as a theater and book critic for The New York Times and The New Yorker.

But before all of that, he first worked after college as an editor for the American Jewish Chronicle, one of the earliest English-language Jewish publications, then distributed nationally once a week. You can read the first issue online here: Published in May 1916, it featured contributions from luminaries such as I.L. Peretz and Ahad Ha’am.

Not big with the Nazis

In 1935, the man nicknamed “Mank” was writing for MGM when Nazi propaganda mastermind Joseph Goebbels sent the studio a letter saying that none of the films Mankiewicz was involved in would be shown in Germany — unless his name was removed from the credits.

According to a New York Times obituary, Mankiewicz didn’t do his status in Nazi Germany any favors by working on a project called “The Mad Dog of Europe,” which satirized Hitler but in the end was abandoned “on advice of influential American Jews, who feared it might militate against their co-religionists in Germany.”

The Anti-Defamation League also “feared it would provoke accusations of Jewish warmongering, and they worried that if it failed commercially, it would demonstrate American apathy to Hitler or even pave the way for pro-Nazi films,” explains an article in Commentary on the film that was never made.

An unadvertised identity

Mankiewicz was just one of the many influential Jews in the early days of Hollywood working in all facets of the industry. But even as the Nazis were aware of them, most did not telegraph their Jewish identities, especially as the Hollywood blacklist — spurred on by the anti-communist sentiment of people like Sen. Joe McCarthy and FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover — grew in influence in the 1940s and ’50s.

As his grandson Ben told the Forward in May, “Most of them had to, if not hide it, hide that it mattered, that part of their identity. They felt very strongly, ‘we can’t let our Judaism influence the tone and texture of the art, of the films,’ because they knew they were succeeding in a world rich with anti-Semitism.”

(Ben also said in the interview that his father, Frank, Herman’s son, grew up in an “observant Jewish household.” So Herman clearly passed on some religiosity.)

The important Jewish character in “Citizen Kane”

Mankiewicz and Welles had a famously contentious relationship that boiled over during and after the making of “Citizen Kane,” as they publicly tussled over who deserved the limelight in the wake of the film’s success. Welles is often seen as the only star of the project, which he was onscreen as the lead actor — but a 1971 New Yorker article by the renowned (and Jewish) film critic Pauline Kael muddied that narrative and gave Mankiewicz not only joint but sole credit for the movie’s lauded script.

Regardless, Welles was interestingly “very fascinated and crazy about all things Jewish,” the director Peter Bogdanovich told Tablet in 2011, and “a big fan of the Yiddish art theater.” That sentiment likely formed out of Welles’ friendly relationship with a doctor named Maurice Bernstein who was close with his family, Bogdanovich theorized.

In “Citizen Kane,” which is roughly based on the rise of the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, there is a character named Bernstein who sticks by the protagonist Charles Foster Kane’s side through thick and thin, and is usually referred to as the film’s most sympathetic persona.

“[Dr.] Bernstein, who was [Orson’s] legal guardian after his father died, was a very, very important figure in his life. He named Bernstein in the movie as a gesture toward his guardian,” Bogdanovich said in the Tablet interview.

In a twist, Mankiewicz was the one wary of including the clearly Jewish character, especially after the actor Everett Sloane was cast to play the role.

“Everett Sloane is an unsympathetic looking man, and anyways you shouldn’t have two Jews in one scene,” Mankiewicz said about one moment in the film, according to a memo unearthed by Bogdanovich.

Sloane, who was Jewish, had a nose that he thought was too large and despaired over it in striving to become a leading man. Welles would later say that Sloane “must have had 20 operations” on his nose before taking his own life at age 55.

One of the film’s many innovative montages includes one of the earliest examples of a character standing up against anti-Semitism onscreen, as Kane rebukes his first wife Emily’s repulsion to Bernstein during a series of breakfast scenes.

While Mankiewicz and Welles collaborated on much of the script, Tablet’s Harold Heft wrote that Welles penned the breakfast montage on his own.

“The anti-Semitism that existed then was largely from the Jews themselves,” Bogdanovich said.

Historical novel on Holland’s largest Holocaust rescue operation slammed for ‘awful’ errors

AMSTERDAM (JTA) — It was meant as an ode to one of the most courageous yet little-known rescue efforts of Jews during the Holocaust.

But a week after its publication, a Dutch-language historical novel is at the heart of a controversy over whether the author twisted the historical record in ways that risk distorting public understanding of the genocide.

Critics say “The Nursery,” which is based on a daring rescue operation to smuggle hundreds of Jewish children out of Amsterdam and describes itself on its cover as a “real-life story,” contains dozens of historical inaccuracies. Chief among them is its description of the Jewish Council, a body created by the Nazis to assist in the murder of Dutch Jews but the book describes as an organization established to “make Jews strong together.”

Esther Gobel, a staffer at the National Holocaust Museum of the Netherlands and the author of several nonfiction books on the Holocaust, termed that mistake “just awful” in an interview published Thursday in the Het Parool daily.

“The Jewish Council was set up by the Nazis as a tool to carry out anti-Jewish measures,” Gobel told the newspaper.

Gobel said she welcomed the effort to expose new audiences to the story, “but it needs to happen in the right historical context and accuracy, especially amid rising Holocaust denial and anti-Semitism.”

The author, Elle van Rijn, a non-Jewish soap opera actress turned novelist, told Het Parool that she was “deeply hurt” by the criticism and called it “unfair.” Van Rijn said she had shared drafts of the book with some of the critics now making the complaints and they had signed off on it.

“I wanted to describe this history with the utmost attention to details,” she said.

Hollands Diep, van Rijn’s publisher, said it “fully stands behind the book,” which Elco Lenstra, a company spokesperson, stressed was being marketed as a novel.

“Anyone is free to write a novel about any subject,” Lenstra told Het Parool.

“The Nursery” — or “De Creche” in Dutch — has appeared at a time of continued popular interest in the Holocaust. Michael Berenbaum, a former project director at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, said in a 2016 interview that the continued glut of Holocaust literature disproves the existence of “Holocaust fatigue.”

Yet as more storytellers choose to address the subject in their work, some are raising concerns about a waning commitment to factual accuracy.

“There seems to be more and more books based on the story of Auschwitz that are not researched properly,” Pawel Sawicki, press officer and educator at the Auschwitz Memorial, told the Irish Times in an interview earlier this year.

“The problem is that readers think, especially when the book is advertised as based on a true story, that everything in the book is accurate and true when in many cases it isn’t,” he added.

Van Rijn’s novel is based on the rescue operation led by Johan van Hulst, who worked at a Protestant religious seminary in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam. The Germans opened a nursery to intern Jewish children in a building adjacent to the seminary while holding their parents across the street at the Hollandsche Schouwburg theater, which the Germans had converted into a prison.

Starting in 1942, a plan was hatched to transfer the children from the nursery, which was run by Jewish staff, across the fence it shared with the seminary, and from there to safety in the countryside. It was by far the largest single rescue operation of Jews in the Netherlands.

Among the other inaccuracies critics have cited is the setting of a Jewish wedding at a department store that Jews were forbidden to enter at the time. The book also represents Henriette Pimentel, the nursery’s director and a key player in the rescue operation, as a lesbian, though there is no factual basis for this. The book also states that she began neglecting some children because she was charmed by a baby named Remi to whom she devoted all of her attention.

The daughter of Sieny Cohen, a nursery volunteer who was part of the rescue operation, also complained about the book, demanding that it be reprinted without her mother’s story and the qualification that it tells a true story.

“This misrepresents my family,” Greta Cune said. “My father’s described as some uncouth guy from Rotterdam, my grandmother as indifferent to deportations. It’s deeply upsetting.”

High-school student leads effort to preserve Vermont’s oldest Jewish cemetery

EAST POULTNEY, Vt. (Bennington Banner via JTA) — The autumn leaves crunched underfoot as Netanel Crispe walked uphill toward the northwest corner of the small cemetery. He stopped and examined a toppled headstone.

“The last time I was here this was standing up,” he said, regarding the weathered, gray stone. “At least it hasn’t broken.”

Crispe brushed away the leaves to reveal a carving at the top of the stone: two raised hands, the gesture used in the delivery of the Birkat Kohanim, Judaism’s priestly blessing.

This is the grave of Marcus Cane, who died on Nov. 13, 1874, and the raised hands are an indication that he was a kohen, a descendant of the sons of Aaron who served as priests in the Temple in Jerusalem.

Cane was a pioneer, one of the first German Jews who made his way to settle in the Slate Valley along the New York-Vermont border in 1868. These families established Vermont’s first Jewish community here in Poultney and left behind this largely forgotten place, the oldest Jewish cemetery in Vermont.

Before this summer Crispe, 18, a senior at Burr and Burton Academy in Manchester, was unaware that the cemetery existed. Now he’s leading an effort to restore and preserve the site.

“I decided it’s my responsibility to honor these pioneers and preserve their history because it’s vital to the history of our state,” Crispe said.

Crispe first learned of the cemetery while doing some metal detecting in town on behalf of a historical society.

“I came across a house that I was told was a synagogue,” he said. The family who owned the house “mentioned that there was a Jewish cemetery in town, and I was blown away because I had no idea.”

As both a 10th-generation Vermonter and an Orthodox Jew, Crispe is keenly interested in the history of Jewish life in the Green Mountain State.

“There are not many Jews in the area, so every time I meet one, it’s amazing,” he said.

The homeowner gave Crispe directions to the cemetery, but even so it was difficult to find.

“This was all grown up,” he said, waving his hand toward the entrance, “and I couldn’t even see the gate. But I finally found it on my third attempt.”

Expecting that it might be a marked-off corner of a larger burial ground, as is the case for many other Jewish cemeteries in Vermont, Crispe was “shocked” to find that it was a full, half-acre cemetery.

“And then I was really just disappointed to see how so many of the older stones are fallen down, broken, although many of them are in good shape,” he said.

The cemetery contains some 60 to 85 graves – there are no conclusive records. Most of the graves date from the 19th and 20th centuries. A handful, parts of family plots that date back decades, are more recent. Cane was the first person buried here, and his wife, Elisa, was the third.

Who were these settlers, and where have their descendants gone?

“Those were the two big questions that I was asking myself as well,” Crispe said.

The oldest Jewish cemetery in Vermont was created by Jewish immigrants from Germany in the 19th century. (David LaChance/Bennington Banner)

His research led him to “’Members of this Book’: The Pinkas of Vermont’s First Jewish Congregation” by Robert S. Schine, a professor of Jewish studies at Middlebury College. A pinkas is a notebook, a record of events kept by a Jewish community, and Poultney’s pinkas had somehow survived, discovered in a used bookstore in Denver in 1966.

Schine writes that he had written to the American Jewish Archives at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati looking for any information about the Jews of the Slate Valley. The one item in the collection was the pinkas, written between 1867 and 1874 in German, with Hebrew and English bits intertwined.

Through the pinkas, Crispe learned that Poultney’s Jews had arrived from Germany around the time of the Civil War, drawn to the area’s booming slate industry. Predominantly peddlers in Europe, these new Americans became the shopkeepers, tailors and grocers for Poultney and Fair Haven, as well as Granville, New York, and environs.

“They were peddlers traveling around just with whatever they had on their back and their small skills, finding jobs here and there, but when they came to America, this was like a new life for them,” Crispe said. “They established and basically became a strong Jewish community here.”

The center of the new community was Poultney, where an upstairs room in the house owned by Isaac Cane, one of Marcus’s sons, was used for services. The congregation purchased a Torah, and later a second, from New York, and bought a half-acre of land from the Union Church to serve as its cemetery.

The history of the Jews of Poultney mirrors that of the slate industry itself, which went through booms and busts before collapsing during the Great Depression in the 1930s. By the 1890s, the Jewish community had disbanded. Some went to Rutland, others to New York, and still others to Ohio and the Midwest.

Crispe has been unable to find any further traces of the founders of the Poultney Jewish community. However, he has made contact with 15 to 20 members of families who came later.

“They’re just so happy to see that something’s being done and that their family hasn’t been forgotten in this way,” he said. “It’s been incredible hearing their stories, seeing the pictures they’ve been able to send me and placing a face on the stones, really being able to connect with these people.”

There are unanswered questions, among them the disappearance of both Torahs. Crispe said it’s possible that one was taken by a member of the congregation when he moved away, and that the second might have gone to a congregation in Rutland. The deed for the cemetery has long gone missing – “no one has the slightest clue where it might be, or if it still even exists,” he said – and so the town has taken responsibility for the site.

Crispe has a threefold plan: Restore and preserve the cemetery and all of its stones; create a fund to ensure that it can be maintained in perpetuity; and obtain official recognition of the cemetery’s historical status.

“I’m applying for a state historic marker to be placed here, and I want to get a nice gate – if we can raise the funds – that says Poultney Hebrew Cemetery, which is what it’s referred to,” he said.

“I’ve been connected with different historical societies, museums, the town of course, and different Jewish communities around the state. It’s a collective effort.”

Crispe has established a GoFundMe account – Save Vermont’s Oldest Jewish Cemetery – which had raised nearly $7,000 by early December.

Ideally he would like to add to the cemetery a genizah, a place for the proper disposal of worn-out or damaged Jewish religious items.

“I’ve contacted different rabbis in the state and most synagogues don’t actually have one,” he said. “They would love to have something like that available.”

“Really the main goal of the project is to reunite the Jewish communities of Vermont, bring together the Jewish life with the secular life and the communities of Poultney and the surrounding areas, and really just bring people together with a great kind of goal and mission in these troubling times.”

Crispe has dedicated himself to helping to preserve the state’s historic places. They’re not as secure as some Vermonters may think, he warns.

“Although we have so many historic buildings, and you see history everywhere around us … we’re losing it every year because there’s no laws preventing it,” he said. “If we lose our history, we lose our identity.”

My mom is Japanese and my dad is Jewish. Their love is not a punchline.

A version of this article originally appeared on Alma.

I’m the daughter of a white Jewish-American dad and a Japanese immigrant mom, and I grew up in Alabama.

As you can guess, this made life growing up in the American Deep South quite interesting. Amid the external anti-Semitism and racism I faced, the internal joke within the Jewish and Asian communities that my parents were meant for each other hurts the most; it translates into a gross invalidation of my parents’ love. Although it could be plausible that the two groups can bond over shared minority experiences, the more nefarious explanation for this so-called “perfect match” is the model minority myth.

My parents met in a “meet cute” fashion of situational fate. My mom won the opportunity to tour the Yokosuka naval base twice as a civilian. Who was the handsome American sailor serving as the tour guide both times? My dad. The family joke is that my mother “won the lottery twice.”

After the two fell in love, I was born in a U.S. naval hospital in Italy with an Italian birth certificate, a Japanese birth certificate and an American birth certificate. After my dad retired from the Navy, we moved to an area with an infamous history of hostility toward people of color and non-Christians: sweet home Alabama.

Growing up, I experienced “othering” from the white and Christian communities in my hometown of Montgomery. When I was a Hebrew school teacher for my synagogue, a police officer was stationed every week to ensure that we could meet safely. Students in elementary school would invite me to their mega-church services and try to “save” me from my impending doom in hell. My mom packed what other kids would call “smelly” lunches and gawk at the bento box items that I thought were far better than their Lunchable pizzas. Many people assumed I was great at math, but after asking me for help, they quickly realized otherwise.

I’ve been called “exotic looking” and have heard a variety of attempts at the ethnic guessing game. Every so often, even outside the South, I get a confused stare. People try to decipher my mixed identity by just … staring at me, hoping to identify what isn’t normal, what isn’t white.

While the racism and discrimination I faced was painful, the lasting pain has come from the communities I call my own. Time after time, I hear from both Asian-American and Jewish-American communities a joke that the two groups are so similar; that my parents come from two extremely “learned” communities; that my parents are such a perfect relationship match. A worse joke is how “Jewish guys have a thing for Asian chicks” — straight-up fetishization. When we take the time to unpack the reactions to this match, we arrive at the deeply planted American model minority myth.

When I was applying for colleges, a counselor (who was Jewish) advised that I focus my entrance essay on my Asian and Jewish identities because the two communities “highly value education, and others just don’t.” I was taken aback, but it was only recently that I’ve been able to identify why that remark made me uncomfortable. The implication behind my college counselor’s statement is rooted in the model minority myth: that Asians and Jews are somehow smarter or more “learned,” and that other minority communities (Black, Latinx, etc.) aren’t. Embracing the idea that Jews and Asians achieve higher economic success in the U.S. from a “pull yourself by your bootstraps” mentality is weaponized against other minorities.

The obvious difference between the story of the African-American community and the Asian-American and Jewish-American communities is clear: Black people came here enslaved. Jews and most Asian people did not. Yet white people and other minorities consistently fail to make the connection of how the history of slavery in this country forever shapes the Black American experience in entirely harsher and more systematic ways. On top of this, both Asian Americans and Jewish Americans often fail to address their anti-Blackness.

To begin to rectify this, we must dismiss the notion that the American minority experience is monolithic. By comparing experiences of minorities in the U.S. based on “economic success,” which unfortunately decides the assessment of overall “success” in this country, the premise perpetuates the false notion that if you simply adopt a strong work ethic, you will “succeed.” It buys into the myth that the “American dream” is a tangible goal that supposedly ignores barriers formed by race, gender, faith and other identities. We must stop holding up Asian and Jewish communities as examples of “success” while ignoring the systemic barriers facing other minority communities.

The intersection of my identities doesn’t create the ideal student/worker/contributor to a capitalist system. My parents don’t love each other because they’re supposedly smarter or supposedly harder workers. They don’t love each other because they’re learned individuals who relate to one another on some shared value placed on education. They love each other because they make each other laugh.

Orthodox Groups Lead Conservative Court Battles Over Religion

(JTA) — Orthodox Jews have embraced a “religious liberty” agenda in one of the busiest years ever for attorneys representing various groups and synagogues.

A recent Supreme Court victory for Agudath Israel of America, challenging New York State’s Covid-19 restrictions, is the latest in a series of court battles by Orthodox groups. Suits have challenged other pandemic restrictions and sought public funding for private schooling, and groups have supported efforts to exempt businesses from laws and regulations that go against their religious beliefs.

“More and more, the action will be in the judicial arena,” Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel, Agudath Israel’s executive vice president, told JTA, “because the legal challenges to our way of life are coming up with greater frequency and we have to turn to the court to protect us.”

In the more than 30 years that Zwiebel has worked at Agudath Israel, an umbrella organization and advocacy group representing charedi Orthodox Jews, he can’t remember a single year where as much of the group’s work took place in court.

There was the lawsuit challenging New York state for applying different standards on attendance at houses of worship than at businesses. Agudath Israel filed an amicus brief supporting the plaintiffs.

There was the case in which Orthodox summer camp directors sued the same state for shutting down overnight camps. Agudath Israel backed the camps.

There was the case in June, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a state-run scholarship program funded by tax-deductible gifts could not exclude religious schools. Agudath Israel had filed a brief in favor of the plaintiff, a parent who wanted to use the scholarship to send her children to a religious school.

And just last week, there was the late-night victory that resounded across America: The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the organization’s petition against Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s restrictions on houses of worship in areas with climbing Covid cases. In what the group hailed as a “high court victory for religious liberty,” the court ruled that Cuomo could not restrict capacity in houses of worship to 10 or 25 people regardless of building size while businesses were allowed to operate in the same areas without capacity restrictions.

The ruling against Cuomo was the latest in a series of Supreme Court decisions on religion in the public space that Orthodox Jews have seen as critical. The agenda isn’t new — it’s been a central priority for as long as Orthodox Jews have been involved in advocacy.

But the centrality of the issue to Orthodox Jews has become more apparent as high-profile social issues have thrust religion into conflict with other values. Agudath supported Hobby Lobby in its successful 2014 Supreme Court case that exempted religiously run corporations from providing contraception in their insurance coverage.

Agudah also filed a brief in support of a Colorado baker who refused to bake a cake for a gay couple’s wedding. The Orthodox Union joined an amicus brief in support of a Catholic agency in Philadelphia that was excluded from the city’s foster-care system because it does not work with same-sex couples.

Agudah has also fought against campaigns and state guidelines calling for higher secular education standards in yeshivas.

The pandemic has made the conflicts over religious liberties even starker.

“In a non-pandemic world, you just wouldn’t have things like capacity limits on a house of worship, so there’s just a lot more opportunity,” said Akiva Shapiro, a lawyer who challenged Cuomo’s Covid restrictions on behalf of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn. (The court decided the Diocese and Agudah cases together.) “In a regular time, things don’t move so fast and so radically.”

What’s Changed

The clash between religious values and secular law exploded on the streets of Brooklyn in October as Orthodox Jews there protested closures of synagogues and yeshivas due to rising Covid cases.

“What has changed in recent years is the self-confidence and asserting that very loudly into the public sphere,” said Rivka Schwartz, an associate principal at SAR High School in the Bronx’s Riverdale neighborhood. A research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute, she writes frequently about politics and the Orthodox community.

The public discourse on religious liberty, particularly high-profile Supreme Court cases that turn on the issue, has contributed to the rightward political shift among American Orthodox Jews. The perception of stronger support for Israel within the Republican Party has drawn some Orthodox Jews to the political right. But for many Orthodox Jews — particularly the charedim, or ultra-Orthodox, most of whom would not identify as Zionists — religious liberty has become the key issue binding them to the GOP.