(JTA) — In a recent review of cartoonist Edward Sorel’s new autobiography, Sadie Stein’s description of a quintessential New York upbringing is worth quoting in full:

Sorel came into the world as Edward Schwartz in 1929. He adored his smart and beautiful Romanian-born mother; meanwhile his father, who’d immigrated from Poland, was “stupid, insensitive, grouchy, meanspirited, faultfinding, and a racist.” Their working-class Bronx neighborhood was pretty evenly divided between card-carrying Communists, Communist sympathizers and New Deal Democrats; Aunt Jeanette, the self-anointed family intellectual, “felt compelled, when there was a band playing at one of her sisters’ weddings, to use her long scarf to do a solo dance in the manner of Isadora Duncan — another fervent supporter of the Communist regime in Russia.” His world was shtetl-tiny but filled with opportunity; provincial but progressive; jaundiced, but optimistic — “a city where being Jewish, far from setting you apart, was a reminder of just how ordinary you were.”

I love the efficiency with which Stein, via Sorel, conjures up a familiar 20th-century Jewish New York archetype. The kicker is that last line by Sorel: “a city where being Jewish, far from setting you apart, was a reminder of just how ordinary you were.” By the middle of the last century, when Sorel came of age, New York’s Jewish population would peak at about 2 million, meaning Jews were one-quarter of the city’s population.

There are still some 1.5 million Jews in the New York metropolitan area — nothing to sneeze at, but now only about 12% of the city’s residents. The Jewish cultural and civic mark on the city is still outsized, which can be seen in the ways “New York” is sometimes used as a codeword for “Jewish” (often by dog-whistling politicians) or shorthand for a distinct way of being Jewish — and a New Yorker. Last week, during its fundraising drive, public radio station WNYC offered a New Yorker magazine subscription for gifts of $180. If that is not the most Jewish offer you have ever seen, I don’t know what is. (If you have any confusion about the symbolism of a $180 gift, read my colleague Philissa Cramer’s breakdown of the recent anonymous $180,000 donation to City College.)

WNYC’s offer is packed with New York Jewish markers, of the liberal, Upper West Side, NPR-listening, New Yorker-reading variety. It reminds me of “Annie Hall,” when Woody Allen’s character reduces a date to a Jewish stereotype: “You’re like New York, Jewish, left-wing, liberal, intellectual, Central Park West, Brandeis University, the socialist summer camps and… the father with the Ben Shahn drawings, right, and the really, y’know, strike-oriented kind of, red diaper … stop me before I make a complete imbecile of myself.”

I am not sure how any of these cultural stereotypes register with anyone under the age of 40. In 1978, Alfred Kazin could write a memoir called “New York Jew,” and most readers would know what he meant before opening the book. In 1976, Irving Howe wrote “World of Our Fathers” — about Eastern European Jewish immigrant life in New York City — confident it would be read and treasured by Jews whose fathers and mothers may never have set foot in New York, except for a brief touchdown on Ellis Island.

Today? The liberal, Central Park West labels certainly apply to a large percentage of Jewish New Yorkers, in spirit if not in fact, although the fastest growing segment of the city’s Jewish population are Orthodox Jews who neither vote Democratic nor live in Manhattan. Russian Jewish immigrants and their children tend to be conservative voters as well — they hear “socialist” and think of Soviet oppression, not striking garment workers or the coöperative-housing movement.

Syrian Jews in Flatbush have their own Jewish story to tell, and Democrats can’t assume that Jews on Wall Street will vote for them or contribute — at least not exclusively — to their campaigns.

And yet, the classic idea of a “New York Jew” hangs on in the widening gap between nostalgia and present-day reality. In an essay for Alma, 19-year-old Hanah Bloom, born and raised in Alabama, writes that she’s a southerner who has “never been to a Jewish deli, nor did I have the big youth group experience with a large congregation.” And yet, thanks to Fran Lebowitz (age 71) and the Netflix series “Pretend it’s a City” — an ode to the city from perhaps the quintessential New York Jew — Bloom feels like “I, too, could be a Jewish New Yorker.”

In her book “Beyond the Synagogue,” Rachel B. Gross asserts that nostalgia is a powerful instrument for forming Jewish identity, going so far as describing nostalgia as “a central aspect of American Jewish religion.” Traditionalists might agree with her when it comes to, say, remembering the Temples or “never forgetting” the communities destroyed by the Nazis.

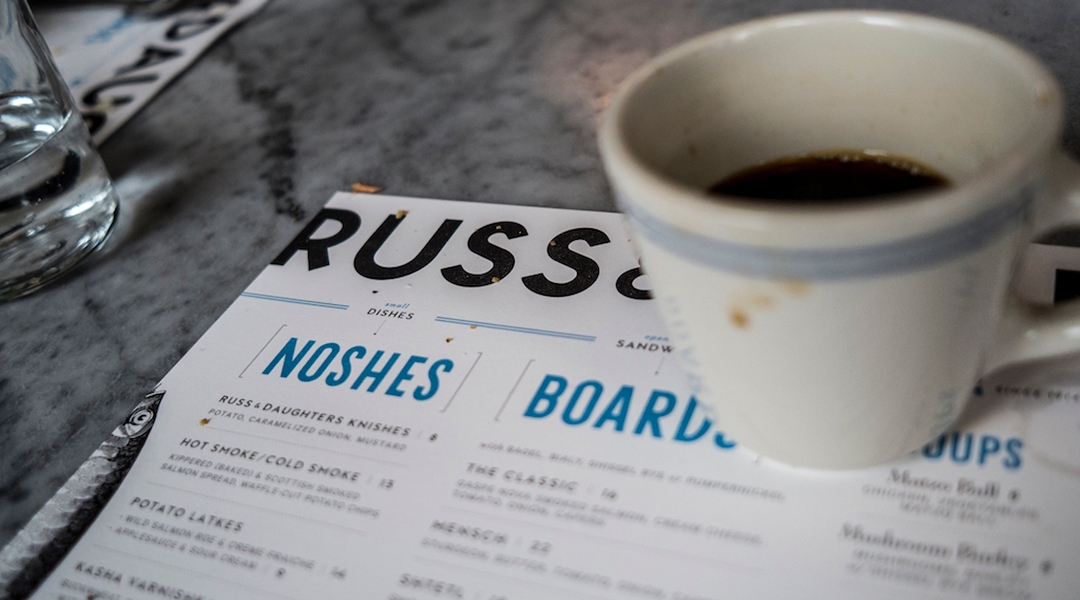

But she is also talking about nostalgia for more recent or seemingly ephemeral culture like deli food, the immigrant experience or the artifacts and stories preserved in Jewish museums. Finding meaning in these things can “establish really sacred relationships between people, the divine and ancestors,” Gross told me last year.

For New York nostalgists, then, “World of Our Fathers” is a holy text, Zabar’s is a pilgrimage site and Fran Lebowitz is “America’s rabbi.”

I know the temptation. I frequently write or edit stories pining for a lost or fast-fading New York. Fetishizing the “New York Jew,” however, is not without its dangers. It ignores the diversity that is fast coming to define not just the city’s Jews, but Jewish communities around the world. It puts the Ashkenazi experience front and center in a way that crowds out Sephardim. It preserves one way of being Jewish in amber. And it reduces proud Jewish communities around the country, with their own stories to tell, to footnotes in a story written by and about people who think you cannot get a decent bagel outside of the five boroughs. (Which is true, but shhh!)

In Stein’s review of Sorel’s book, after rhapsodizing about his upbringing in the Bronx, she writes this: “This was a depression-era New York of Third Avenue Els, Friday night chicken soup, Saturday matinees and — lest we get nostalgic — no penicillin. When 7-year-old Edward contracted double pneumonia, it meant an at-home oxygen tent and a year’s convalescence, during which time he started drawing on shirt cardboards.”

In other words, nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.