This article is also available as a weekly newsletter, “Life Stories,” where we remember those who made an outsize impact in the Jewish world — or just left their community a better or more interesting place. Subscribe here to get “Life Stories” in your inbox every Tuesday.

Tamar Fishman, 88, Judaica pioneer who designed a Hanukkah stamp

Born in Israel in 1935, Tamar Fishman was part of a cohort of late 20th century Judaica artists — including David Moss, Betsy Plotkin Teutsch, Jay Greenspan and Jeanette Kuvin Oren — who revived Jewish folk art traditions that might otherwise have been lost.

Fishman created intricate papercuts and wedding contracts, or ketubot, and the tapestries she designed for her synagogue, Congregation Beth El of Bethesda, Maryland. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan gave a specially commissioned papercut she created to Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin on the occasion of his state visit.

But in 2018 she got a commission that would literally put Fishman in wide circulation: Her papercut design of a menorah was chosen for a U.S. Postal Service stamp, issued jointly with Israel, celebrating Hanukkah. “You keep growing and just don’t stop,” Fishman, then 82, said after a ceremony at the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, unveiling the stamp. “That’s the work of my hands.”

Fishman died Aug. 14 in Bethesda. She was 88.

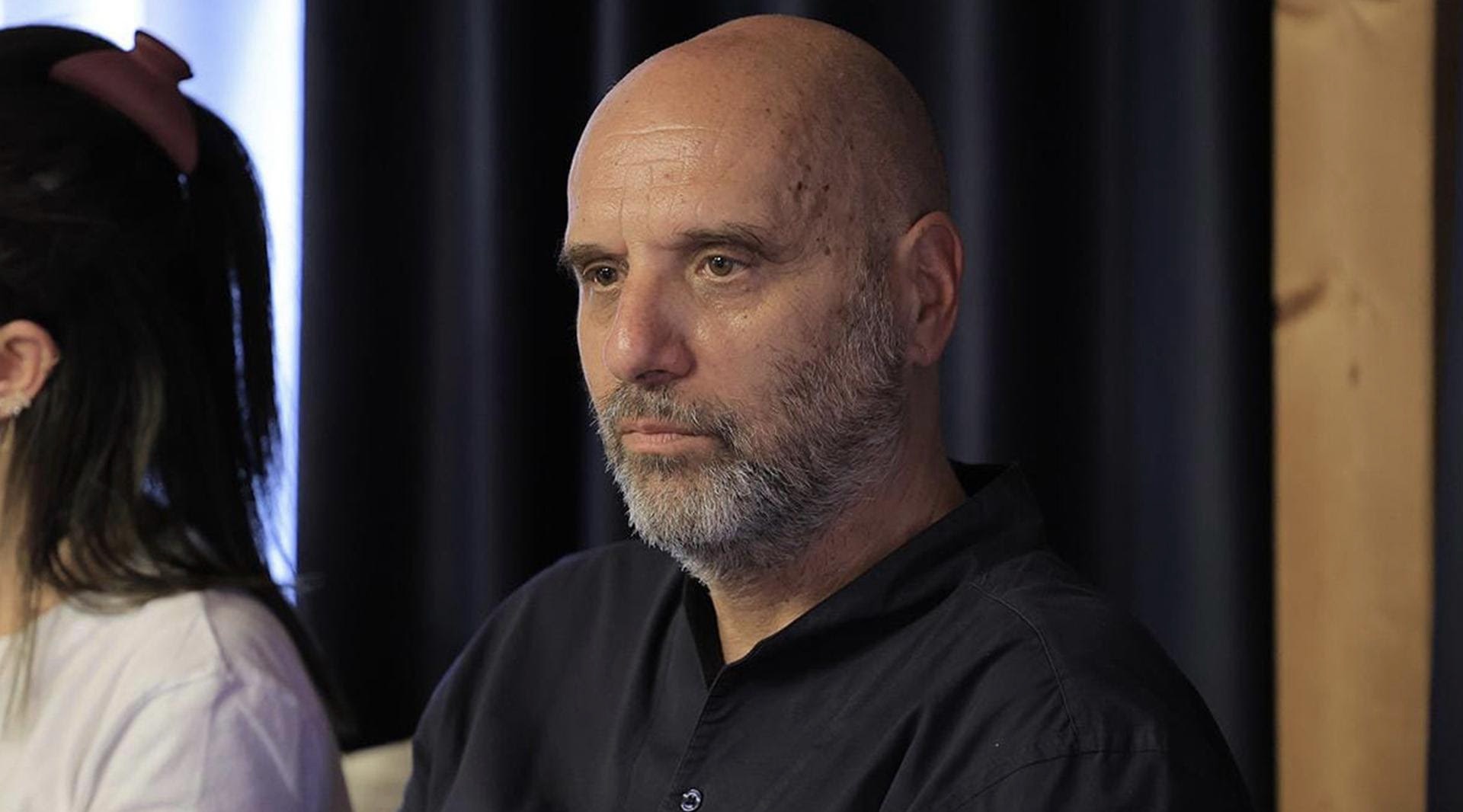

Seth Bloom, 49, a circus clown on a humanitarian mission

Seth Bloom, right, and his wife Christina Gelsone, the New York clown duo Acrobuffos, perform on Copacabana Beach, London, England, Aug. 8, 2016. (Ian Gavan/Getty Images)

Seth Bloom’s father was a Foreign Service officer and his mother an adviser for the World Food Program. The family lived in countries as diverse as Sri Lanka and Kenya, maintaining their Jewish traditions, but also celebrating with their Christian, Buddhist and Hindu neighbors.

Bloom followed in his parents’ humanitarian footsteps, albeit obliquely: He trained as a clown, performing with major circuses and partnering with his wife Christina Gelsone (above) on two-person shows known for their wit and beauty. Starting in 2003, in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion that overthrew the Taliban, he developed a troupe in Afghanistan that featured circus arts to teach lessons about health and social issues.

“I was going to areas that no media was going to and no one was taking positive pictures of kids laughing, and mullahs laughing and old guys with donkey carts pulling up to watch our shows,” he told a blogger in 2016.

Bloom, 49, died Aug. 2 in Poughkeepsie, New York. His wife said he died by suicide after suffering chronic pain for a number of years.

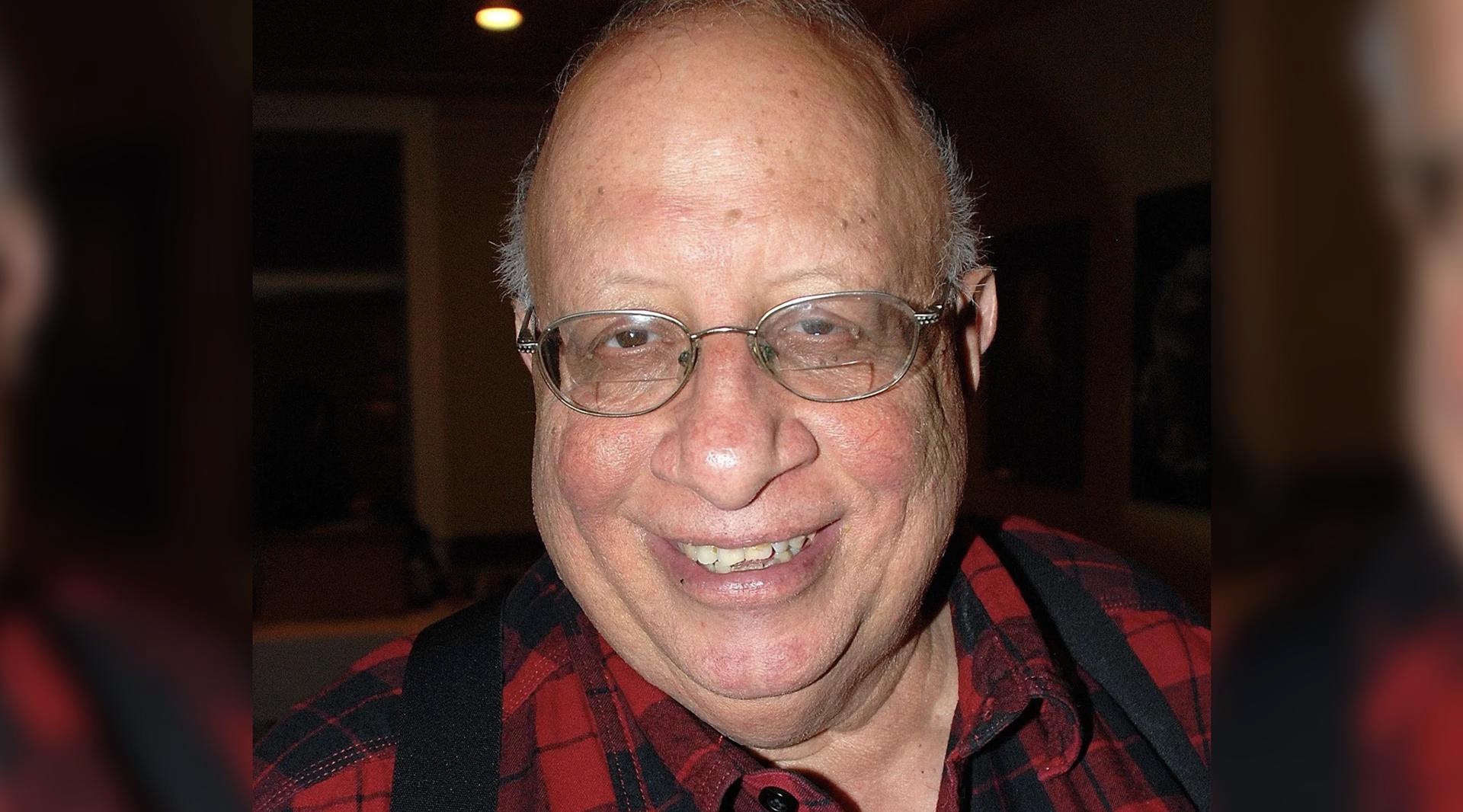

Seth Wolitz, 86, a Yiddish scholar deep in the heart of Texas

Seth L. Wolitz’s books included 2014’s “Yiddish Modernism: Studies in Twentieth-Century Eastern European Jewish Culture.” (Slavica Publishers, Indiana University)

Seth Wolitz liked to tell the story of the racist Maryland crabbers who nearly cut off his finger when he was returning from a summer of civil rights activism in the early 1960s. Somehow, the experience inspired his affection for Marcel Proust, and early in his career, Wolitz was principally known as a scholar of French literature and especially of the work of the French-Jewish writer.

Later, however, as the Gale Chair and the Director of Jewish Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, he became a foremost expert on Yiddish Modernism and the writer Isaac Bashevis Singer. He was also instrumental in expanding Jewish Studies at UT-Austin, recruiting faculty members and organizing lectures, symposia and performances, including a grand Sephardic Festival in 1992.

“Jewish Studies on American campuses,” he once wrote, “are not natural flowerings but were battled for over many odds, carefully planted, nurtured and watered by Jewish money and still not securely fastened.”

Wolitz died in Austin on Aug. 11. He was 86.

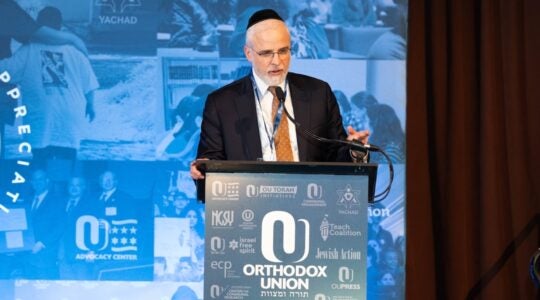

Shai Doron, 64, ‘Jerusalem’s best friend’

Jerusalem Foundation President Shai Doron dedicated his life to Jerusalem and its residents. (Courtesy Jerusalem Foundation)

“Jerusalem has lost its best friend,” Rabbi Joy Levitt wrote in a tribute to Shai Doron, the president of the Jerusalem Foundation, former head of the city’s beloved zoo and a pillar of Jerusalem’s environmental, philanthropic and civic life.

A fourth-generation Jerusalemite, Doron was a protege of the city’s legendary mayor, Teddy Kollek, serving as his chief of staff until 1993. For 25 years, Doron led Jerusalem’s Tisch Zoological Gardens, transforming it into a major attraction and spearheading important projects to preserve and protect many animal species from extinction.

As president of the Jerusalem Foundation starting in 2018, he directed philanthropy meant to beautify the capital and strengthen its complex civic infrastructure. “He worked to advance shared society and to bridge the gaps between Jerusalem’s diverse communities and to provide equal opportunities for all,” the foundation said in a statement.

Doron died of a heart attack July 30. He was 64.

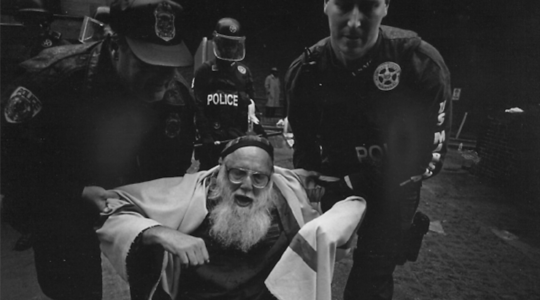

Ira Grupper, 80, a champion of civil rights and Mideast peace

Ira Grupper’s family remembered him as a “proud troublemaker.” (Courtesy Kentucky State AFL-CIO)

Ira Grupper was 13 and growing up in an Orthodox Jewish home in Brooklyn when he felt drawn to the civil rights movement. He participated in the pro-integration New York school boycott of 1964 and left Brooklyn College for Mississippi in 1965 to campaign for voting rights.

He would eventually have a hand in nearly every major social movement of the next 60 years, as an activist with the Congress of Racial Equality, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the NAACP. From 1991-1993 he was the national chairman of the New Jewish Agenda, a progressive Jewish organization that pressed for an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal despite major pushback from the Jewish mainstream.

A resident of Louisville, Kentucky, he worked on the assembly line at the Philip Morris cigarette factory for decades, where he also served as a union shop steward. In his retirement, he taught civil rights and Middle East Studies classes at Bellarmine University.

“You don’t get anything without fighting for it. You don’t keep anything unless you continue to fight for it,” he said in an oral history interview in 2011. “We see that every day. We see many of the gains that we’ve won being taken away.”

Grupper died July 23. He was 80.

Žilvinas Beliauskas, 66, a Lithuanian librarian dedicated to the country’s Jewish history

Zilvinas Beliauskas regularly spoke at the Jewish Library Association’s annual conference about his work preserving and promoting Jewish culture in Lithuania. (Courtesy Jewish Community Library via Facebook)

The Vilnius Jewish Public Library was established by the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture in 2011 at the impetus of Wyman Brent, a California book collector who is neither Jewish nor speaks Lithuanian. In order to achieve its goal of demonstrating the breadth and depth of Jewish life and culture in the former center of Jewish cultural, economic nd intellectual life, the library would need a stellar director.

The library found the ideal candidate in Žilvinas Beliauskas, who had a master’s degree in psychology from Vilnius University and had done postgraduate studies in its Department of History of Philosophy and Logic. Perhaps more importantly, he shared Brent’s commitment to remembering the cultural contributions of a community of Jews whose storied history ended with the Holocaust.

“Not Jewish himself, he devoted an enormous amount of energy to educating fellow Lithuanians about Lithuanian Jewish history and heritage,” the Jewish Community Library in San Francisco remembered in a Facebook tribute.

Beliauskas, who also directed the Vilnius Jewish Theater, died July 26. He was 66.

Walter Arlen, 103, a Jewish refugee whose music grappled with his past

Walter Arlen (born Walter Aptowitzer, Vienna, July 31, 1920) was an American composer and music critic for the Los Angeles Times. (Via YouTube)

After fleeing the Nazis in Austria in 1938 at 18, Walter Arlen at first set aside the musical talent that had made him a rising star in his native Vienna, instead getting a job in a Chicago factory so he could bring the rest of his family to the United States from England.

But when a psychiatrist suggested composition as a form of therapy, he returned to music, ultimately becoming an influential critic and convener of classical music in Los Angeles.

In the 1980s, Arlen returned to writing his own music, composing works that grappled with the trauma of displacement, memories of witnessing the murder of an elderly Jew in Vienna and the deaths by suicide of several loved ones, including his mother. At 95, he released an album titled “Memories of an Exiled Wandering Viennese Jew”; four years later, he composed a score for the 1924 silent film “The City Without Jews.”

Among those feting him on his 100th birthday in 2020 was a Vienna center dedicated to amplifying artists like him who had been banned by the Nazis.

Arlen died last September at 103, but his death was only recently confirmed to The New York Times by his husband of 65 years, Howard Myers.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.