This article is also available as a weekly newsletter, “Life Stories,” where we remember those who made an outsize impact in the Jewish world — or just left their community a better or more interesting place. Subscribe here to get “Life Stories” in your inbox every Tuesday.

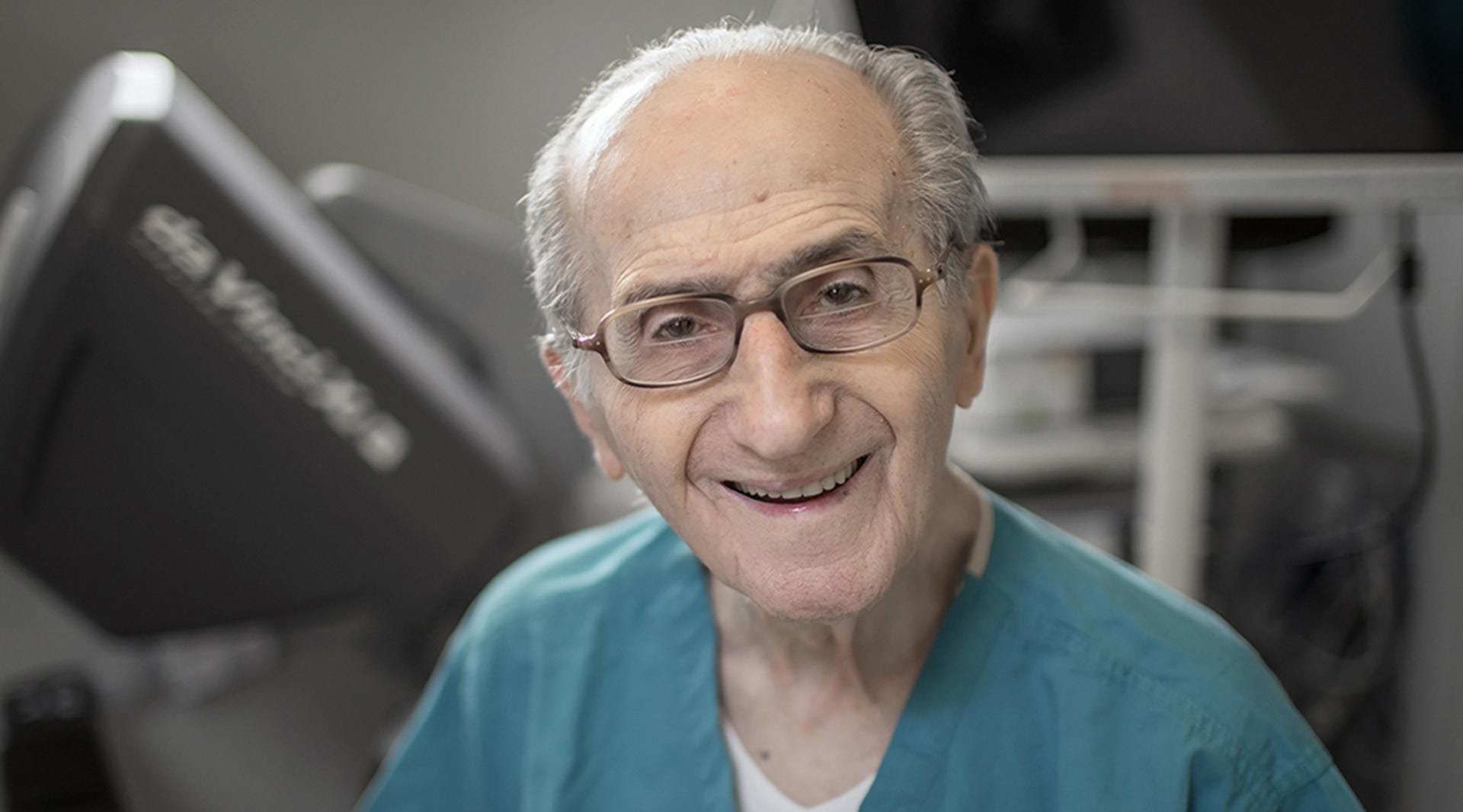

Dr. George Berci, 103, Holocaust survivor who transformed surgery

As a Jew growing up in Hungary after it joined the Axis alliance, George Berci was barred from medical school, so he became an apprentice in an electrical shop and studied mechanical engineering. After surviving forced labor and narrowly avoiding deportation to Auschwitz, he studied as a surgeon in Budapest after World War II and ultimately settled in the United States.

He would go on to combine his medical training and engineering skills for the benefit of millions of people: In a long and illustrious career at Cedars-Sinai medical center in Los Angeles, he developed the tools and techniques of laparoscopy, the “minimally invasive” procedure that allows surgeons to perform delicate operations without gruesome incisions.

Berci was nearly 70 when laparoscopic surgery became the standard in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and he continued to come to work until after he turned 100.

Berci died Aug. 30 in Thousand Oaks, California from complications of COVID-19. He was 103.

“Unfortunately, I had a terrible early life in respect to being a Jew,” Berci said in 2018. “The next generation needs to know about what happened.”

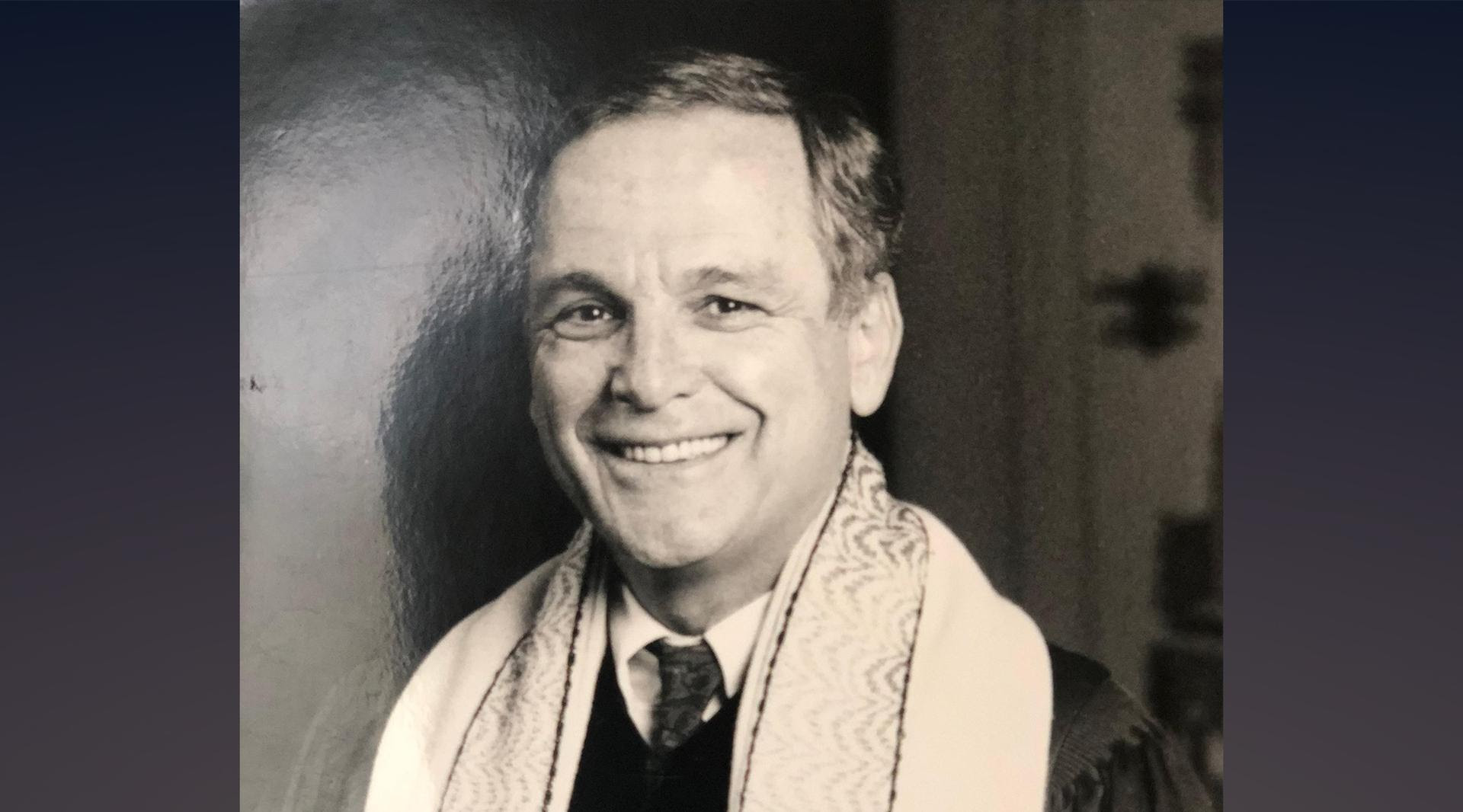

Burt Schuman, 76, Poland’s first Progressive rabbi since the Holocaust

Rabbi Burt E. Schuman served as rabbi of Beit Warszawa, a Progressive congregation in Warsaw, from 2006 to 2012. (Archiwum Rzeczpospolitej)

Rabbi Burt E. Schuman, who in 2006 became Poland’s first Progressive rabbi since the Holocaust, died Sept. 20 in Pittsburgh of chondrosarcoma, a rare bone cancer. He was 76.

Ordained as a Reform rabbi when he was 42, the New York native served as rabbi at Temple Beth Israel in Altoona, Pennsylvania before answering a call to lead Beit Warszawa, a Progressive, or Reform, congregation in Warsaw. There he set about revitalizing a liberal Jewish community that was decimated by the Holocaust, organizing social and cultural events, staging Yiddish musical performances and establishing what he called a “very serious and very demanding” eight-month conversion course. “The more ways one can be Jewish, the stronger the Jewish community is,” Schuman told JTA in 2006. “We’re in the business of making Jews.”

He also initiated a gender-neutral translation of a Reform prayer book into Polish. Such efforts planted a seed for the growth of other Progressive communities among the country’s tiny Jewish population.

Schuman returned to the United States in 2012 and settled in Pittsburgh.

Temma Kinglsey, 82, philanthropist and pillar of her Queens, N.Y. synagogue

Temma Kingsley joined the Forest Hills Jewish Center as a newlywed in 1965. (Legacy.com)

Temma Kingsley was a pillar of the Forest Hills Jewish Center, a Conservative synagogue that long anchored its Queens, New York neighborhood. In 2022, Kingsley, the synagogue’s first woman president, spoke to the New York Jewish Week about the decision to sell its building and find a home for its priceless fixtures, including an ornate ark designed by the artist Arthur Szyk.

An early childhood teacher, director and consultant, Kingsley dedicated her career and philanthropy to Jewish education. She served on the boards of the Zamir Choral Foundation; the former Board of Jewish Education the Davidson School at the Jewish Theological Seminary; was president of the New York Jewish Early Childhood Association and the National Jewish Early Childhood Network; and chaired UJA-Federation’s Interboro Women’s campaign.

“Her exemplary philanthropy … impacted countless lives,” UJA-Federation wrote in a tribute. She died Sept. 8 at age 82.

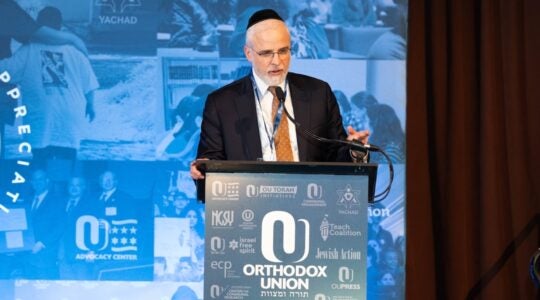

Arnold Sher, 89, the Reform movement’s ‘rabbinate’s rabbi’

Rabbi Arnold I. Sher was the longest serving director of placement of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. (Via Facebook)

When a Long Island dentist sued his rabbi in 1992, saying the rabbi’s advice led to the breakup of his marriage, Rabbi Arnold I. Sher repeated the suggestion he often shared with his rabbinic colleagues: Get yourself malpractice insurance.

It was the kind of counsel he offered with authority: Sher, the longest-serving director of placement at the Reform movement’s Central Conference of American Rabbis, was also a trained lawyer. From 1990 to 2008, he was responsible for finding pulpits for Reform rabbis and for advising rabbis and congregations on employment and governance matters.

Sher also served for 22 years as the spiritual leader and later rabbi emeritus of Congregation B’nai Israel in Bridgeport, Connecticut. As acting executive vice president of the CCAR in 2005, he guided “Mishkan T’filah,” a new Reform prayer book, through its final stages.

In a tribute written after his death on Sept. 15 at age 89, the CCAR called him the “rabbinate’s rabbi,” adding, “He blended care and compassion with realism and seichel (common sense), as he counseled congregations and colleagues.”

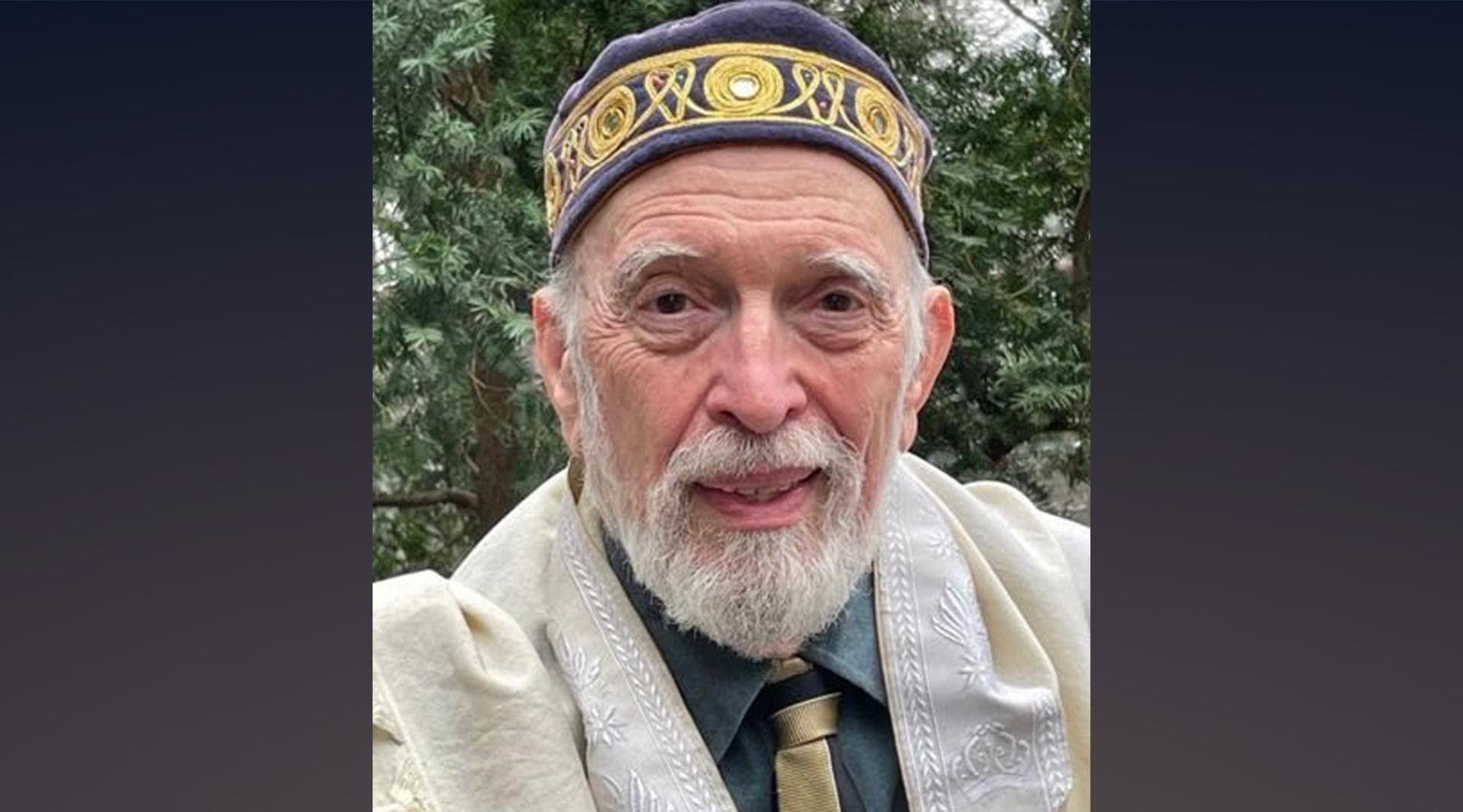

Jack Kessler, 79, an iconoclastic cantor steeped in tradition

Hazzan Jack Kessler was the director of the ALEPH Cantorial Ordination Program, and taught voice and hazzanut. (hazzanjackkessler.com)

Cantor Jack A. Kessler liked to surprise congregations with a technique he adapted from his friend and teacher, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi: He would chant English texts, from the Declaration of Independence to a speech by Martin Luther King Jr., in “trop,” the traditional cantillation used to chant from the Torah and other biblical scrolls.

It was a signature move from a lifetime of making Jewish text, ideas and song, as he once wrote, “both powerful and accessible.” A “hippy before there were hippies,” his niece Suzanne Sbarge remembered, Kessler was a cantor in Conservative synagogues but eventually embraced Schachter-Shalomi’s Jewish Renewal movement. He founded the Hazzanut (cantorial) Department at ALEPH, the movement’s ordination program.

A leader of the klezmer band Goldene Medina, he also founded Atzilut, a group of Jewish and Arab musicians who often raised money for Jewish-Arab reconciliation projects in Israel. “Peace can’t be legislated from above by governments. It has to be desired by the people,” he once told the Jewish Exponent in Philadelphia. Kessler was also a fixture at Congregation P’nai Or in Philadelphia, where his wife Rabbi Marcia Prager is the spiritual leader.

He died Sept. 24 at age 79. In a eulogy, his student Matt Austerklein wrote that Kessler had an uncanny ability to translate traditional cantorial styles for present-day seekers: “[H]is collaborative spirit, disarmingly jocular personality, and immense musical talent seamlessly weaved this old-world aesthetic into a new age fabric.”

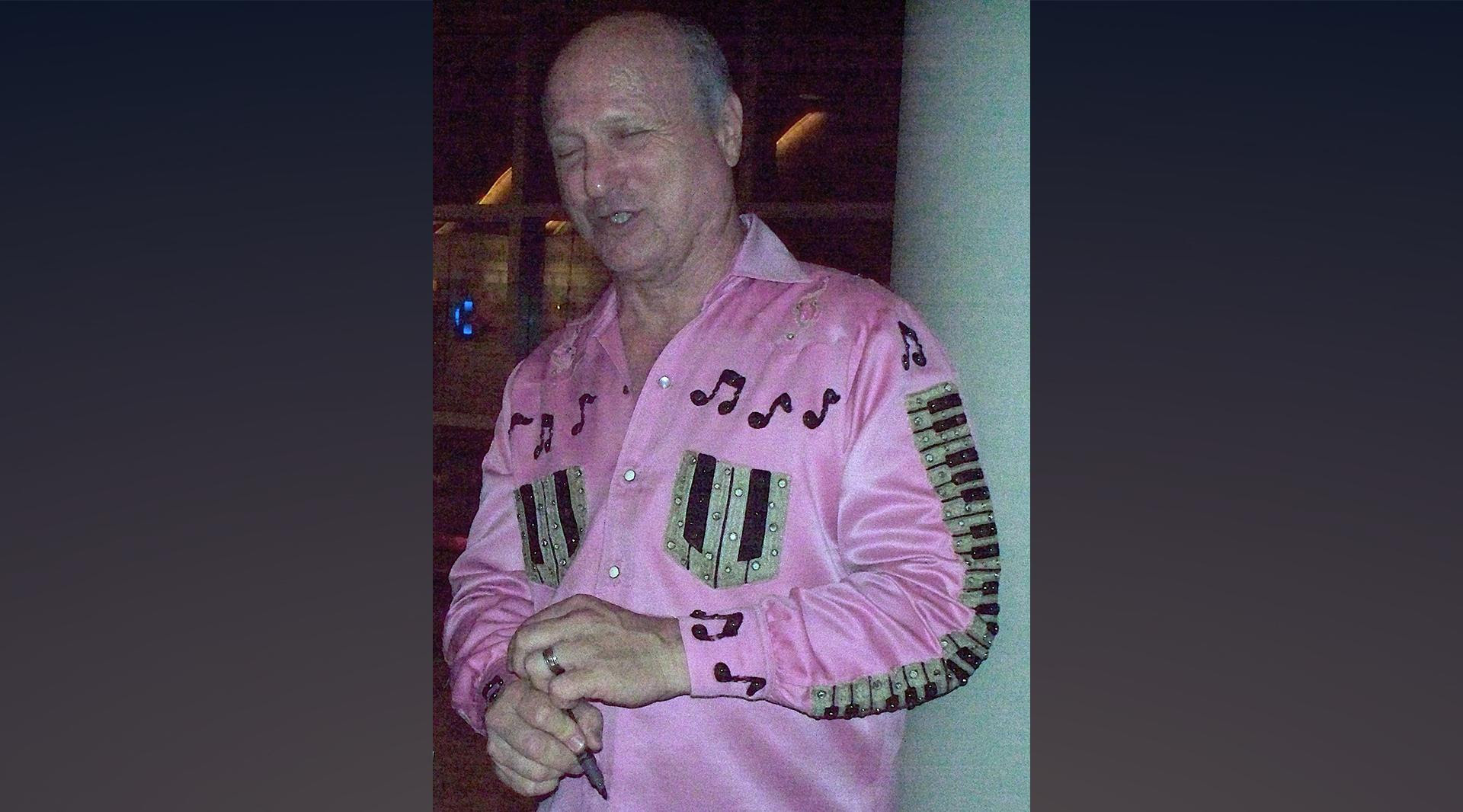

‘Screamin’ Scott’ Simon, 75, pianist and songwriter for Sha Na Na

Screamin’ Scott Simon signs autographs in Seattle, Washington in 2009. (TriviaKing/Wikipedia)

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, Scott Simon was a talented musician who was active in United Synagogue Youth, the Conservative Jewish youth group. At Columbia University in 1970, he answered a “pianist wanted” ad in the student newspaper placed by a 1950s tribute band, formed a year earlier with a lineup that included Alan Cooper, a future provost of the Jewish Theological Seminary.

The band was Sha Na Na, and by then it had already played Woodstock. Under the stage name “Screamin’ Scott” Simon, he performed with the doo-wop group from 1970 to 2022, appeared in all 96 episodes of the TV variety show “Sha Na Na,” had a role in the popular film “Grease” and co-wrote “Sandy,” John Travolta’s hit song from the movie.

Simon died Sept. 5 in Ojai, California. He was 75.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.