Last Tuesday night, the author and podcaster Dan Senor told an enthusiastic crowd at New York’s 92nd Street Y that despite a rising tide of antisemitism and a backlash against Israel’s war in Gaza that has left Jews feeling isolated and vulnerable, the Jewish community had within its power to “create nothing short of a Jewish renaissance.”

If philanthropists and communities double down on supporting Jewish day schools, summer camps, adult Jewish education and gap years in Israel, “I’m optimistic about the Jewish future in the Diaspora, not because the challenges aren’t real they are, but because we really do have the tools to rebuild American Jewish life,” said Senor, delivering 92NY’s annual “The State of World Jewry” speech.

One week earlier, The New Republic published a long article by the journalist and academic Eric Alterman, titled “The Coming Jewish Civil War Over Donald Trump.” It too surveyed the state of world Jewry, but with a markedly different analysis. Alterman sees a Jewish community divided between an influential, politically conservative minority that unconditionally defends Israel and a majority that votes Democratic and prioritizes defending democracy in both Israel and the United States. On the extremes, meanwhile, is a far right that promotes Israel’s annexation of the West Bank and Gaza, and a far left that is non- or anti-Zionist.

For Alterman, the Jewish challenge won’t be resolved by funding Jewish identity programs but confronting, as one liberal Jewish leader tells him, “who gets to define what it means to be Jewish in the U.S.” Does being Jewish mean supporting a hard-right Israeli government and an illiberal Trump administration because it has vowed to fight antisemitism? Or does it mean, as Alterman writes, defending “educational and democratic institutions that have allowed [Jews] to become the safest, most secure, and most economically successful Jewish population to exist anywhere, anytime, ever”?

With the war in Gaza still raging, after 19 months that altered Jewish self-perceptions and perhaps their status in the United States, the two observers laid out visions of the present and future that are both diametrically opposed and in some ways complementary.

Senor, the co-author of the influential book “Start-up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle” and host of the pro-Israel “Call Me Back” podcast,” focused on the resilience of Israel and the rise of antisemitism in the United States. He acknowledged Israel’s “internal fractures,” but also said it has emerged from the war in a better military situation than when it started, having neutralized Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Iran.

Unlike Alterman, he barely mentioned divisions within the Jewish community, instead insisting that the Oct. 7 attacks, the subsequent hostage crisis and anti-Israel backlash have increased Jewish engagement, unity and support for Israel.

“On Oct. 8, suddenly, many embraced their Jewish identity and community. They were pained as their family came under attack. As the scholar Mijal Bitton said, that pain we all felt, that pain you’re feeling is peoplehood,” Senor said. “People started wearing Jewish star necklaces for the first time. They went to rallies. They donated hundreds of millions to emergency campaigns and sent supplies to IDF units, and yes, by the hundreds of thousands, they listened to podcasts about Judaism in Israel.”

The anti-Israel and antisemitic backlash led to “a crack in consciousness,” he said, reminding Jews of other eras in which their safety and security proved fleeting. And while many Jews are itching to fight back against antisemitism and anti-Israel bias in the media, on campus and in international courts, Senor urged a prescription for antisemitism previously offered by a number of prominent Jewish writers, including Dara Horn, Bari Weiss and Sarah Hurwitz: Invest instead in Jewish living and learning, “the one thing we can control.”

Senor sang the praises of Jewish day schools and camps, and of universities — he mentioned Vanderbilt University and Washington University in St. Louis, whose presidents jointly placed a Wall Street Journal ad in March — that he said “push back against the dual erosion of academic excellence and ideological diversity in higher education,” echoing a conservative critique of academia that has gained popularity among Jews stung by the campus upheavals over Israel.

“Scaling these immersive Jewish experiences and investing in a higher education landscape where Jewish flourishing is celebrated would amount to nothing short of a Jewish renaissance,” said Senor. “But this renaissance will not come cheap.”

Senor barely addressed the political diversity or schisms of the Jewish community he was describing. It felt like a “legacy” speech, to borrow Alterman’s taxonomy, reflecting a presumed communal consensus represented by the large, influential Jewish institutions like the Anti-Defamation League, the federations and AIPAC.

Alterman sees a Jewish community whose divides have been widened by the war in Gaza and the election of Donald Trump. He sees the “legacy” organizations battling with the “Next Generation” — something of a misnomer when describing some fairly venerable groups like J Street and the Jewish Council for Public Affairs — who are often critical of Israel and want Jews to reclaim their liberal advocacy role in domestic politics. This “Next Generation” wants to prioritize resistance to the Trump administration, and to a Netanyahu government that “is in the process of attempting to destroy the nation’s democracy from within.”

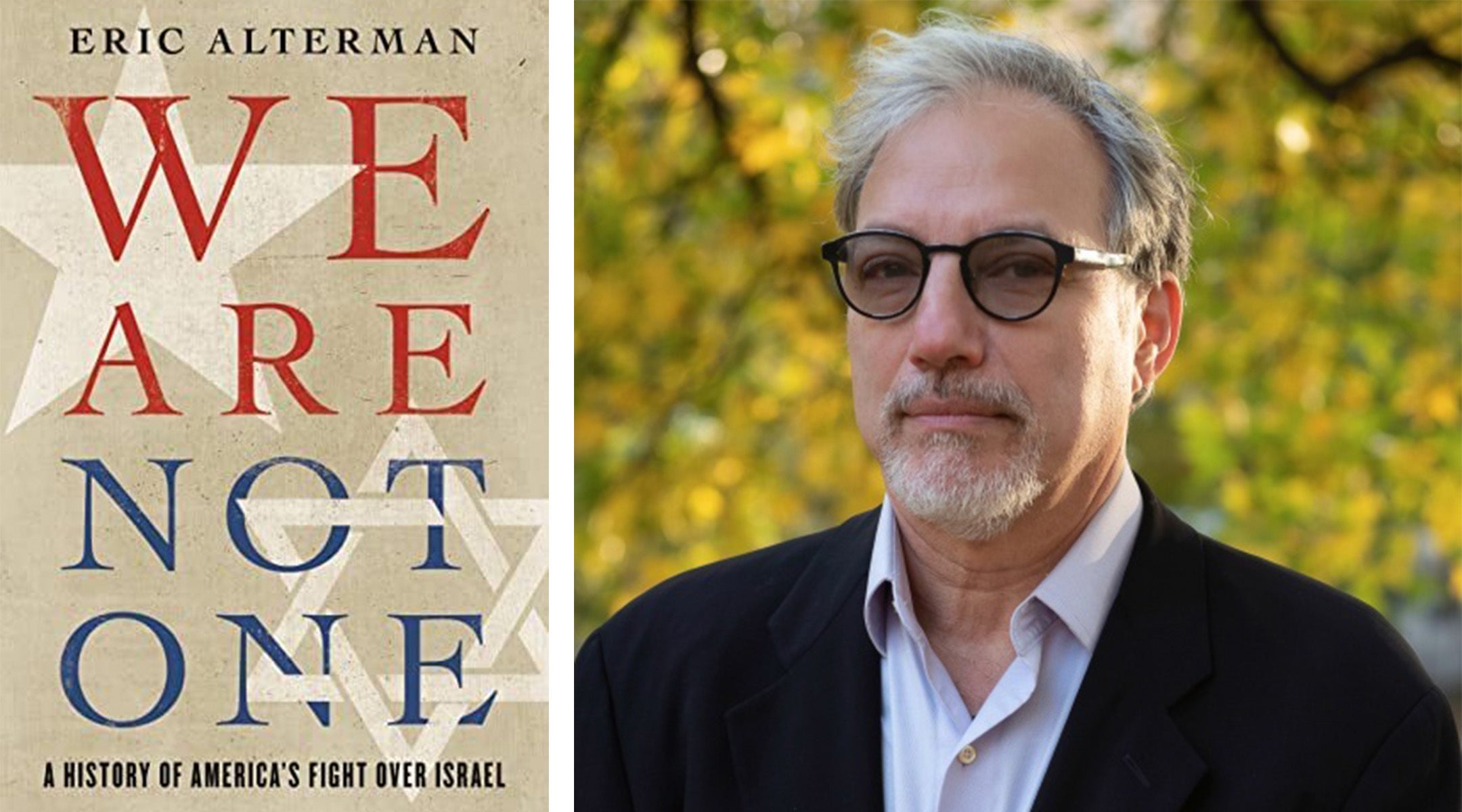

Eric Alterman is the author of “We Are Not One,” a history of the debate over Israel in the United States. (Maresa Patterson; Basic Books)

Alterman writes that he spoke to mostly liberal Jewish American leaders who are in a “panic” over “Trump’s attack on universities and his apparently unconstitutional treatment of pro-Palestinian protesters in the name of combating ‘antisemitism,'” and the threats those actions represent to American democracy.

Senor is worried about young Jews, wondering if they will be able to afford the day schools, camps and gap years in Israel that he says can serve “as a foundation for living a Jewish life.” Alterman is also worried about young Jews, warning they will only become more distanced from Israel as it digs in on the right.

They diverge again when they write about the anti-Israel street protests. Senor compares keffiyeh-wearing pro-Palestinian activists to the neo-Nazis who marched in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017. Alterman warns, however, that “whatever antisemitism may or may not be, it obviously is not manifested in every single student demonstration for Palestinian rights.” Where Senor sees the anti-Israel backlash as another chapter in an age-old story of antisemitism, Alterman quotes Jewish leaders who worry that Israel’s actions in Gaza and the West Bank are creating the conditions that put Jews around the world at risk.

It’s probably too early to say anything definite about “the state of world Jewry” in the wake of Oct. 7, although a number of people have tried. Writers of theology like Shai Held and of recent Jewish history like Joshua Leifer quickly inserted ruminations on the effects of Oct. 7 in books that were already in the works before the attacks. The Jewish Review of Books was early out of the gate with a symposium titled “Before & After October 7.” JTA put together a package of “After Oct. 7” articles on the one-year anniversary of the attacks.

Most of these are first drafts. While the big books are waiting to be written, Senor and Alterman serve as helpful guides to what Jews today are thinking and saying. Both writers are deeply invested in the state of the Jews and the state of Israel. In 2023, Alterman wrote a book, “We Are Not One,” in which he lamented how “legacy” organizations sought to limit what was permissible when Jews talk about Israel. With “Start-Up Nation,” Senor cemented an image of Israel as a high-tech innovator and coined an enduringly popular nickname for the country.

The temptation is to view the two as adversaries, whose arguments and prescriptions are incompatible. Perhaps they are. But it isn’t impossible to imagine a Jewish community that doubles down on Jewish education and identity-building, while committing itself to defending democracy. Or that effectively fights antisemitism without undermining principles and institutions that have served Jews extremely well. Or that supports Israel while leaving room both for criticism, on the one hand, and respect for the hard choices facing a country where half the world’s Jews live, on the other.

Of course that would demand a rapprochement of sorts — an acknowledgement by “legacy” Jews and the “next generation” that they have something to learn from each other, and an agreement to disagree without demonizing the other side.

In 1987, Elie Wiesel gave “The State of World Jewry” talk at the 92nd Street Y, as he did a number of times during his lifetime. ”I am worried not by the outside menace. I am worried by the internal one,” he said at the time. “I mean, by our disunity. I would call it the most serious danger facing the Jewish people today. We are too fragmented, too split, too self-centered, each in his or her own group.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.